|

Title: New information on the dissorophid Conjunctio (Temnospondyli) based on a specimen from the Cutler Formation of Colorado, U.S.A. Authors: B.M. Gee, D. S Berman, A. C. Henrici, J.D. Pardo, A. K. Huttenlocker Journal: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2020.1877152

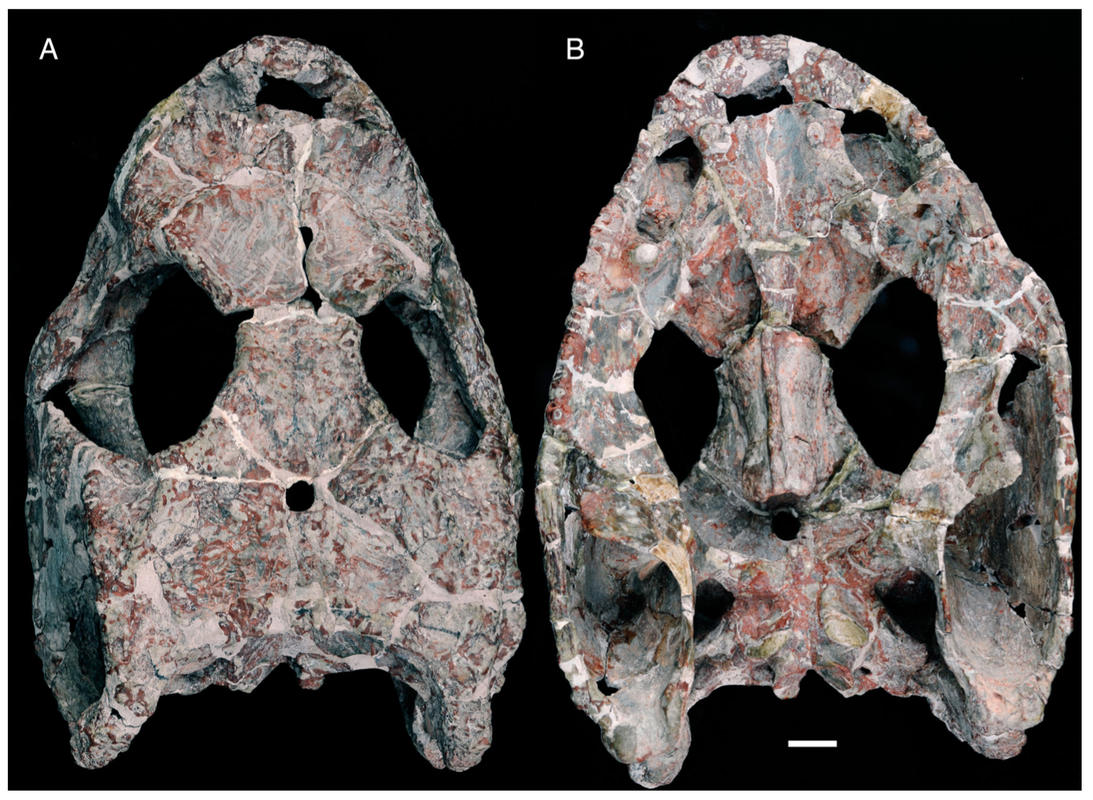

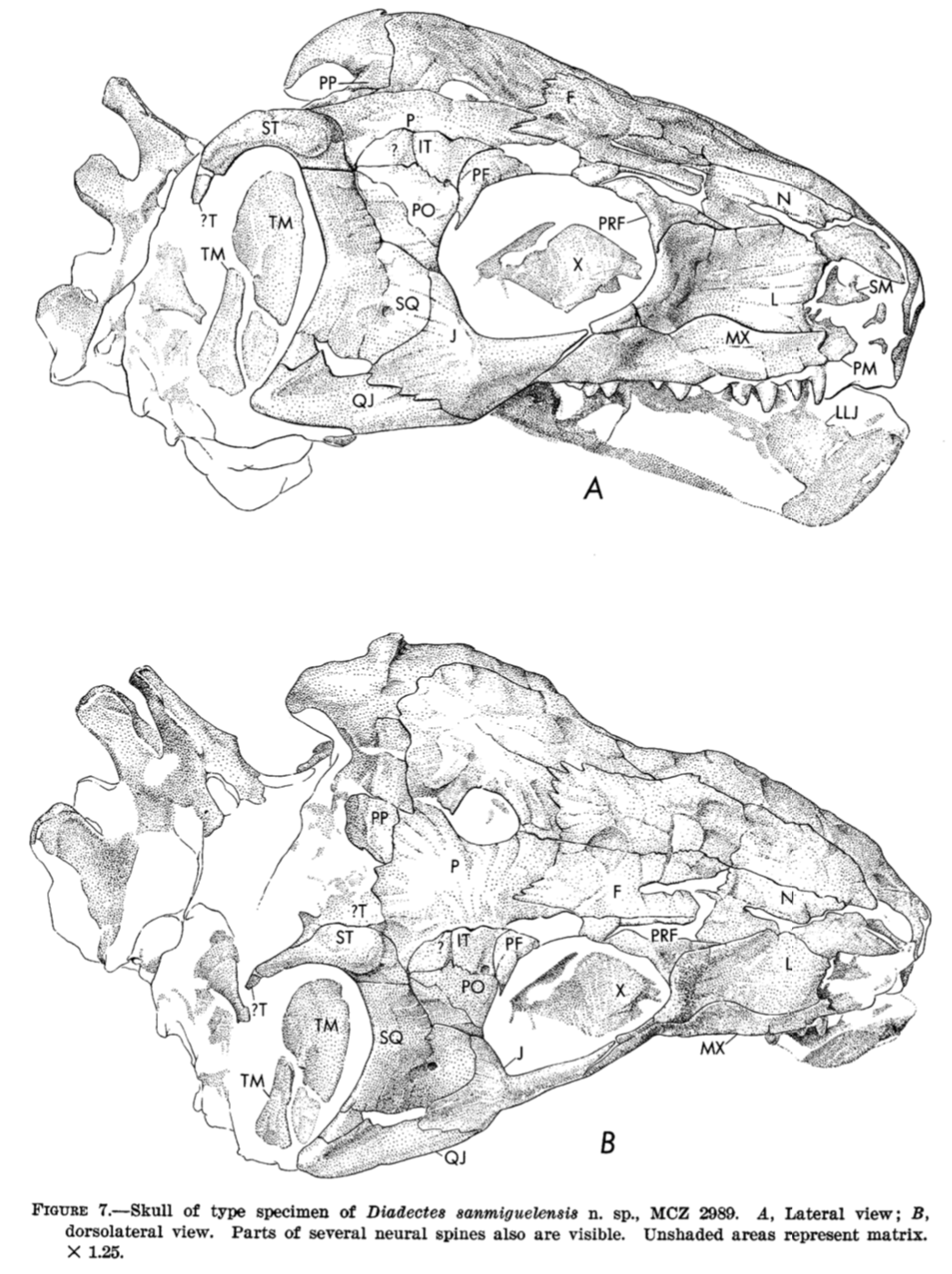

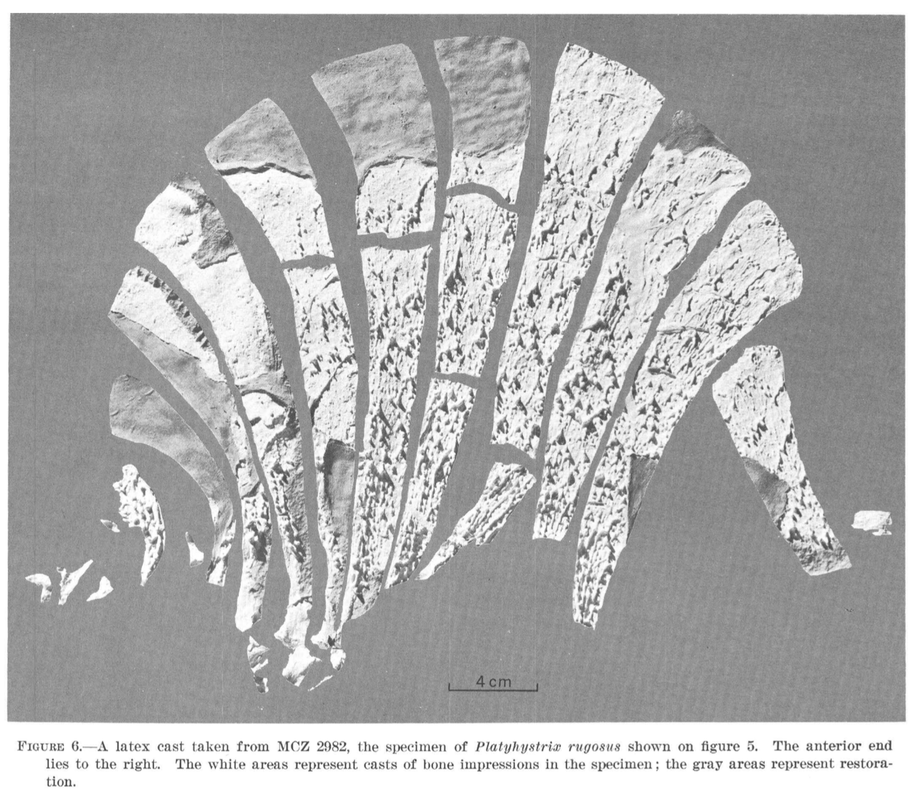

The Red RiverThe Red River is a mostly east-west oriented, eastward-flowing indirect tributary of the Mississippi River, stretching from the Texas Panhandle all the way to Louisiana (over 1,350 miles). It forms the border between Texas and Oklahoma (hence where the "Red River Rivalry" in collegiate football between University of Texas and the University of Oklahoma derives from), two of the most historically productive states for early Permian tetrapod fossils (especially the famed Texas redbeds). Much of our record of North American temnospondyls from this time comes from these two states, with more minor contributions from New Mexico, Utah, and Ohio. Dissorophids, the armoured dissorophoids, are among the best known taxa from these redbed deposits, and in many instances, the entire record of a given species is restricted to one or two states. Whether this is an artifact of the fossil record or an accurate representation of a truly restricted geographic range is often unclear; many taxa are in fact known from only one specimen or one site (the two species of Cacops below are examples; figures from Gee & Reisz, 2018 and Anderson et al., 2020). Land of Enchantment Conjunctio multidens (reconstruction from Schoch & Sues, 2013) is one such dissorophid, known only from two sites (but the same county) in New Mexico. Although New Mexico and Texas are adjacent states, their faunal assemblages were somewhat different, a result of regional geography no longer present that would have created some degree of spatial segregation. Other examples can be found in the trematopids Anconastes and Ecolsonia, only found in New Mexico, or the dissorophid Broiliellus reiszi, which differs starkly from other members of the genus that are known from Texas. Because the Texas redbeds have been so extensively sampled, with at least a dozen other dissorophids known, it can be reasoned that indeed Conjunctio also did not occur in Texas. But does that mean that it was only found in New Mexico? Not necessarily. The rest of the Four Corners region and the midcontinent is less well-explored, probably because the early Permian deposits that yield tetrapod fossils are less extensive. One of the well-known productive localities in the Four Corners region is in the Placerville area in Colorado, where the Cutler Formation (also found in New Mexico) is several hundred meters thick. First reported by Lewis & Vaughn (1965), the assemblage preserves one of the few sails of the dissorophid Platyhystrix (below on right), the holotype of Diadectes sanmiguelensis, a diadectomorph stem amniote (below on left), and a number of other tetrapods also known from other redbeds deposits. Synapsid fans may also know this as the type locality for the sphenacodontid Cutleria.

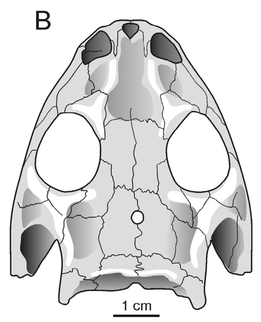

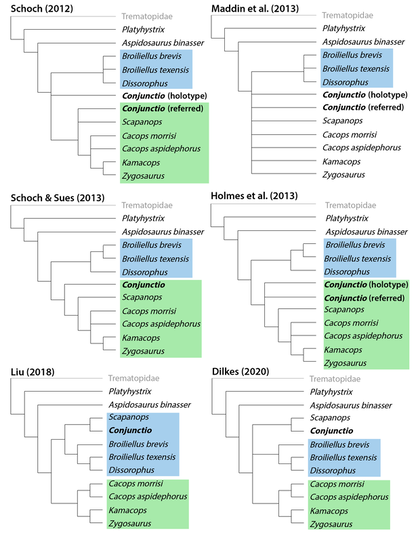

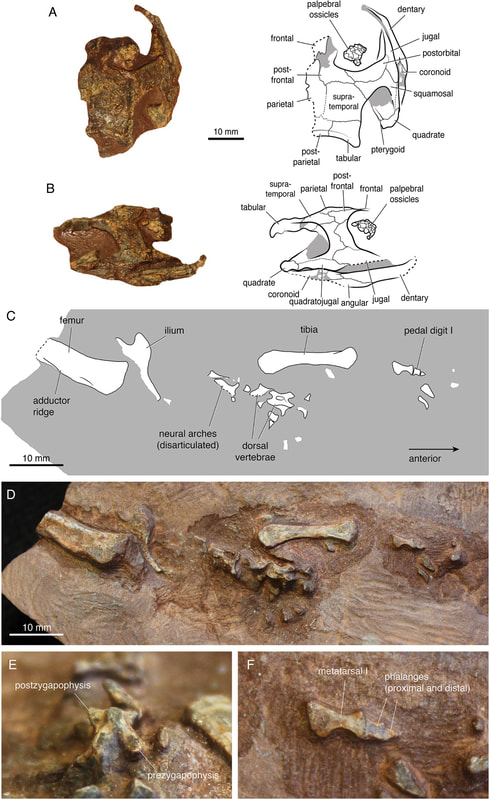

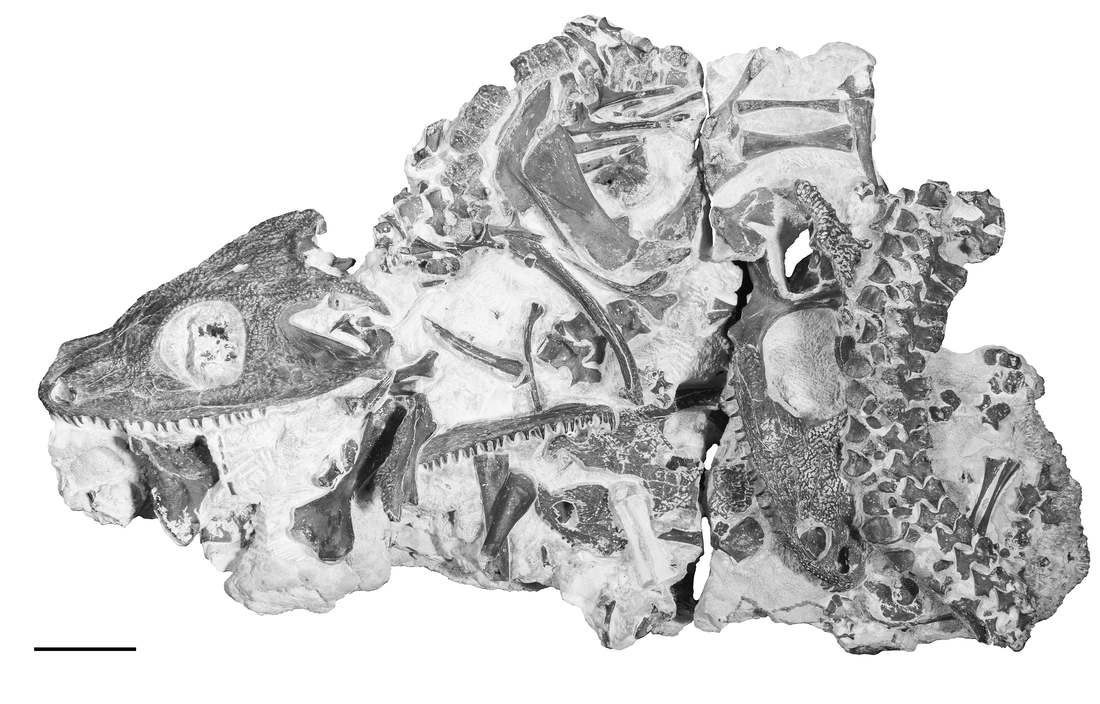

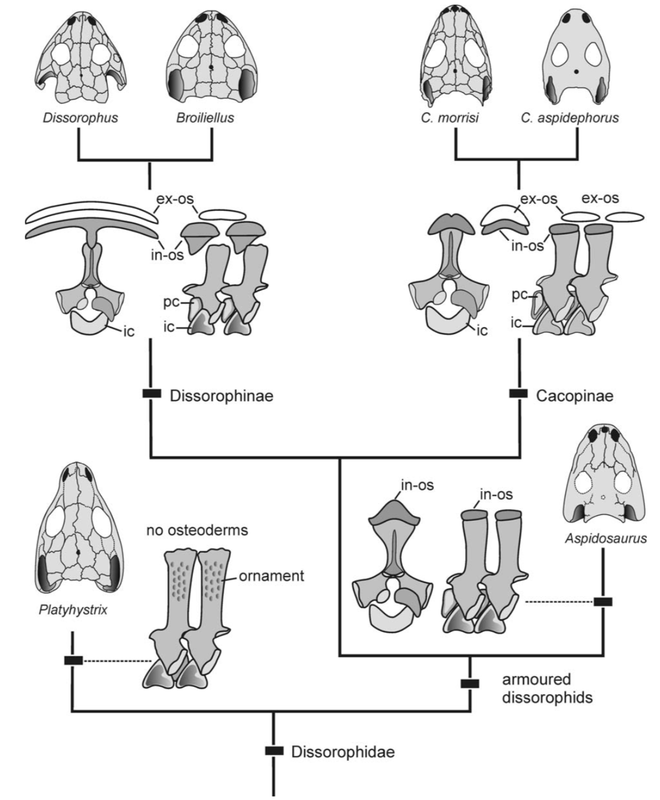

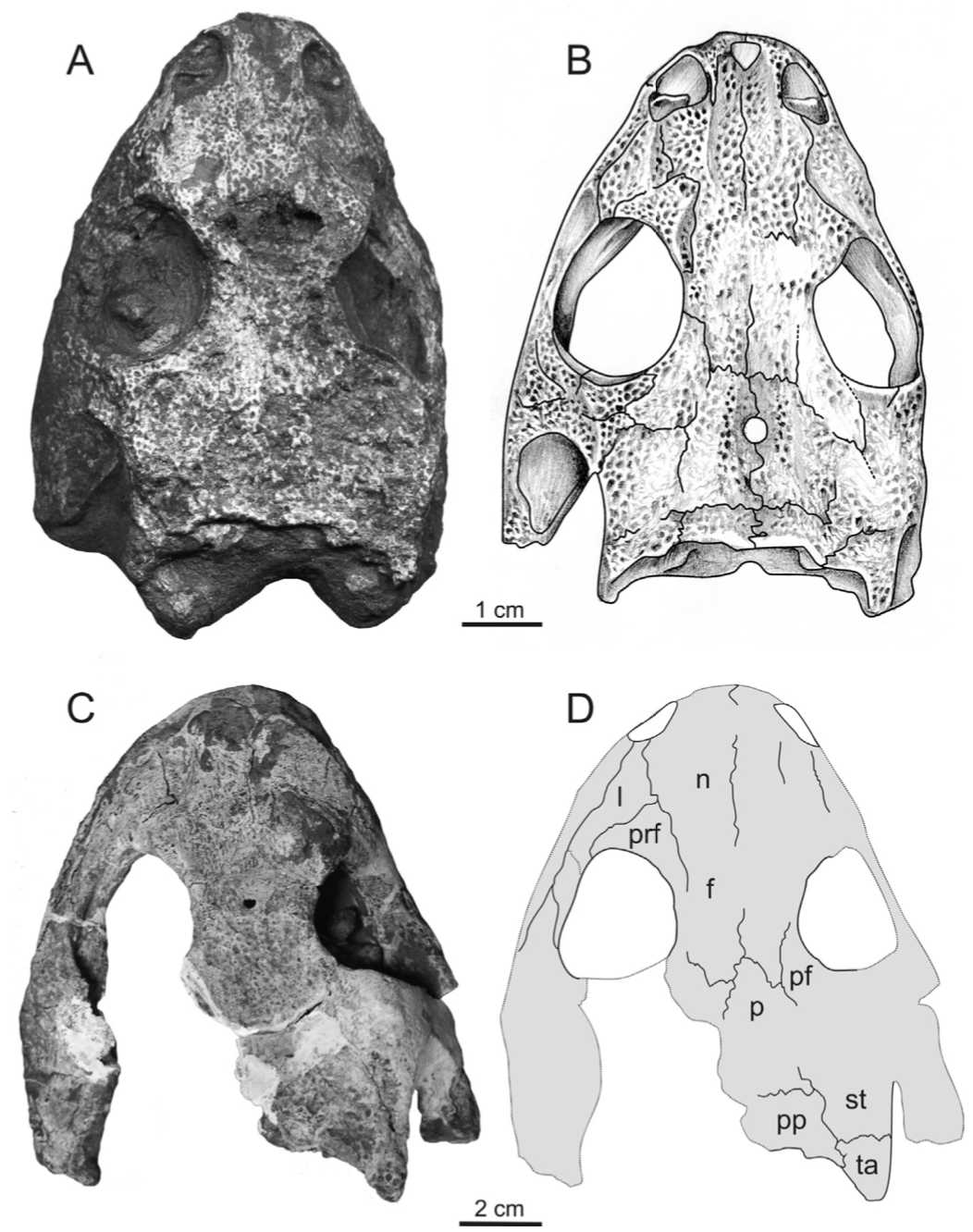

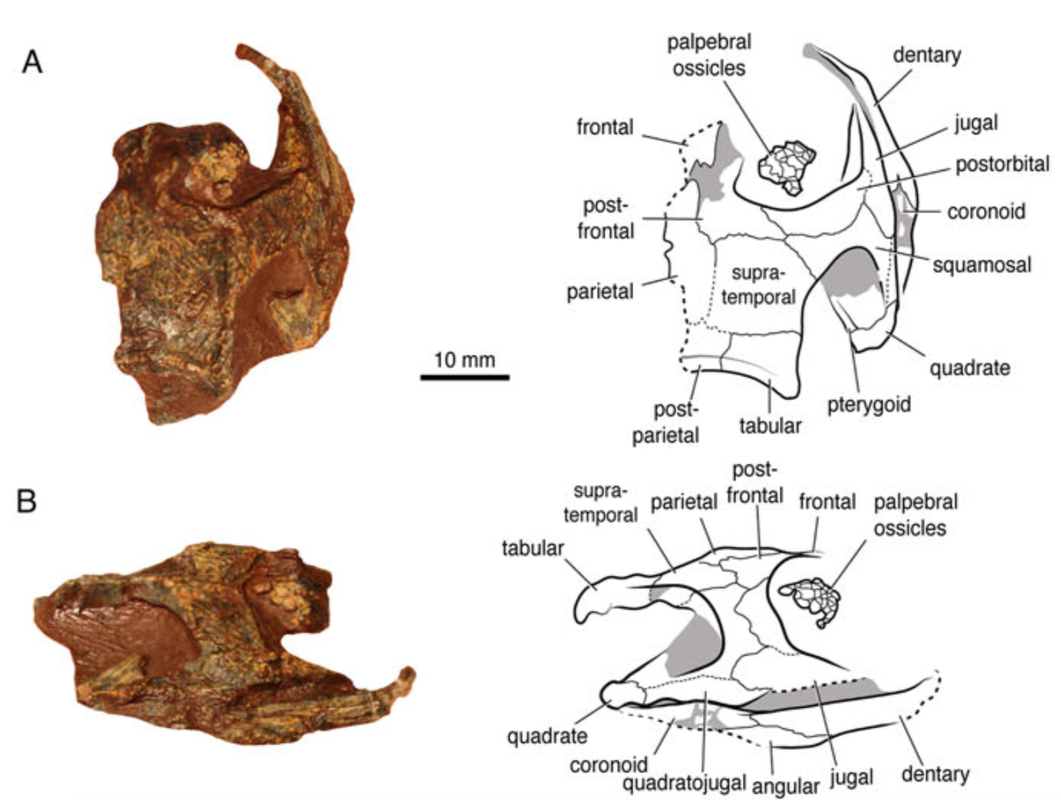

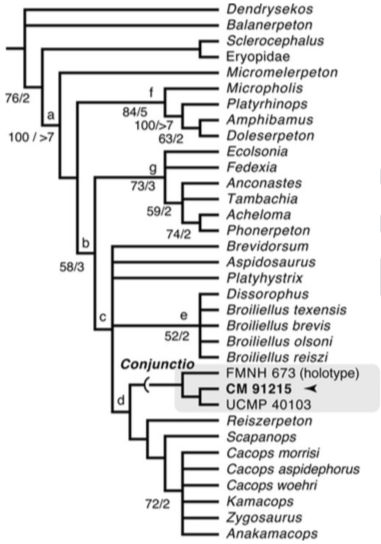

Terminology: While 'transitional form' or 'transitional fossil' is a commonly used term that even the general public knows (e.g., Archaeopteryx), scientists are moving away from it because it's misleading, suggesting that one animal directly turns into another (one of the most common misconceptions about evolution). In fact, this very rarely occurs (a process called anagenesis), and it does not capture major transitions like the theropod-bird transition or the fish-tetrapod transition. Instead, continual splitting of new species that go extinct is what gradually leads to a shift in a group's anatomy. A given species' suite of features may be transitional insofar as it captures part of this shift, but the species or individual itself is not. Agree to disagree Comparison of different phylogenetic results with Conjunctio. Boxes refer to dissorophid subfamilies: green = cacopines, blue = dissorophines. Comparison of different phylogenetic results with Conjunctio. Boxes refer to dissorophid subfamilies: green = cacopines, blue = dissorophines. As one might expect from a taxon with a weird mixture of features, there is no agreement on the position of Conjunctio in phylogenetic analyses of dissorophids, as summarized on the right. Historically, the phylogeny did not support that they were conspecific (expected recovery as exclusive sister taxa), as they were frequently scored separately due to uncertainty over Carroll's referral (the referred specimen was called the "Rio Arriba Taxon"). It doesn't really help that the holotype (C-D) and the much smaller referred specimen (A-B) differ from each other in cranial proportions, somewhat questioning whether they are actually the same taxon (since Bob Carroll created Conjunctio in 1964). You don't have to be a paleontologist to look at the two specimens above and kinda wonder whether they are actually the same (or whether the bottom one can be said to be much of anything really). Sometimes both specimens were recovered as eucacopines (Holmes et al., 2013), sometimes only one was recovered as a eucacopine (Schoch, 2012), sometimes Eucacopinae didn't exist (Maddin et al., 2013), sometimes the composite was recovered as a eucacopine (Schoch & Sues, 2013), and sometimes the composite was recovered as a dissorophine (Liu, 2018). So basically every possible result short of it being recovered as a non-dissorophid! The Centennial StateThe new specimen that we report here was collected from what's known as the Placerville locality by my coauthors, Adam Huttenlocker and Jason Pardo, a few years back. It is not nearly as complete as the other two specimens, but it is well-preserved, enough to show some distinctive features not found in most or all of the other dissorophids. For example, the two bones called the postorbital (right behind the eye) and the supratemporal (a little farther back) usually touch, but here they do not (this is found in two of the species of Cacops as well). The jaw articulation (marked by the quadrate) also sits in front of the level of the back of the skull (marked by the postparietal); this is something found only in Dissorophus and Scapanops. So there is actually quite a lot of information in this little skull despite it being at best 25% complete! Our phylogenetic analysis, which combines two previous matrices (it was originally intended for a larger sample), finally recovers not just the original two specimens, but also this third one as a proper clade (i.e. what you expect if they really do all belong to the same species)! The statistical support is not very good though, and it's quite possible that a future study could find a different result. Dissorophid phylogenetics remains very much in flux outside of just Conjunctio (something that I'm working on right now). COVID addendum: Lest someone think that all of us are superhumans who pumped out this paper in the pandemic, it was mostly completed before the pandemic really set in (we submitted the first version in May 2020). Jason and I in particular as current and recently graduated PhD students have really slowed down in putting new work into the pipeline during the pandemic, which I think is important to note since a lot of people are really struggling and should not be concerned with their perceived relative productivity! Refs

Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed