|

This week's peculiarity is the Triassic temnospondyl Sclerothorax from Germany, a bit of a Frankenstein taxon (I'm stretching the Halloween theme a bit) with a surprising mix of cranial and postcranial anatomy and a weird skull!

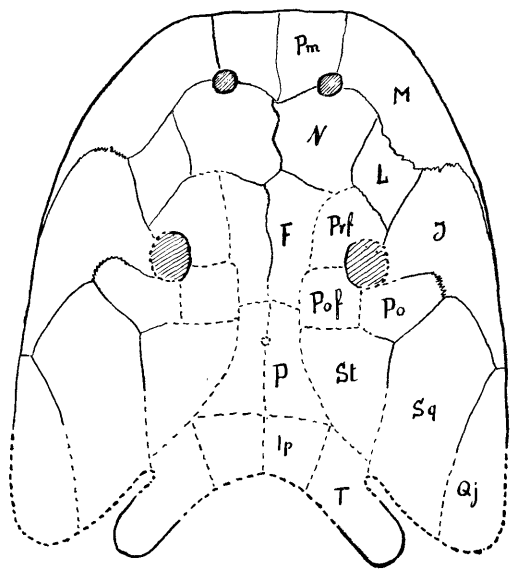

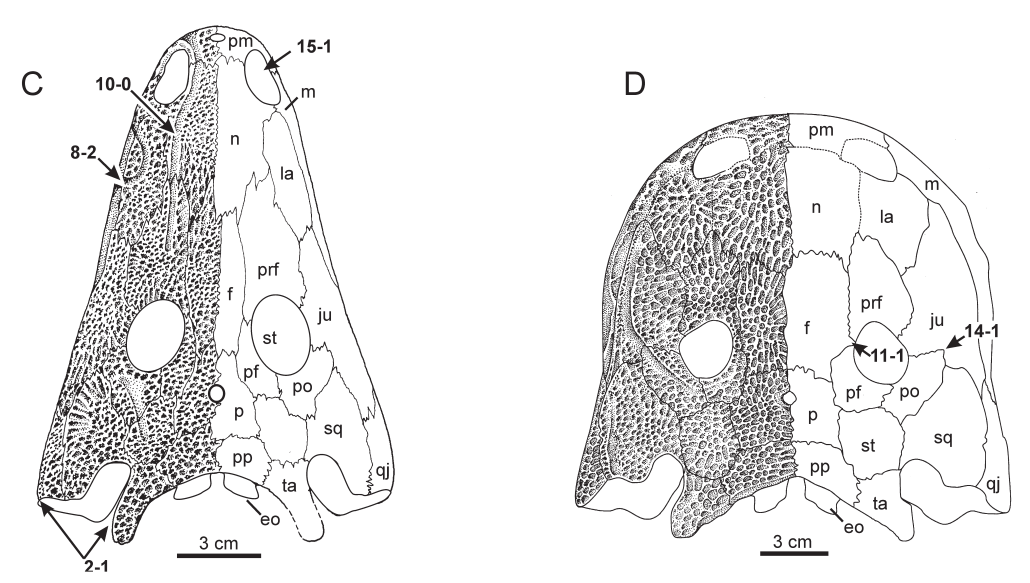

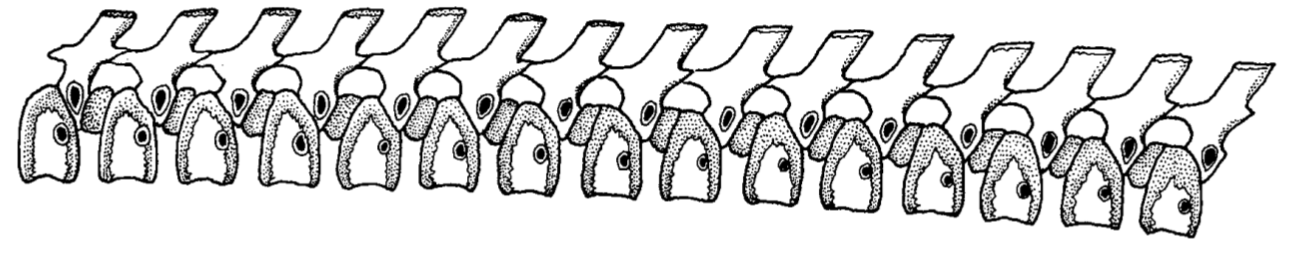

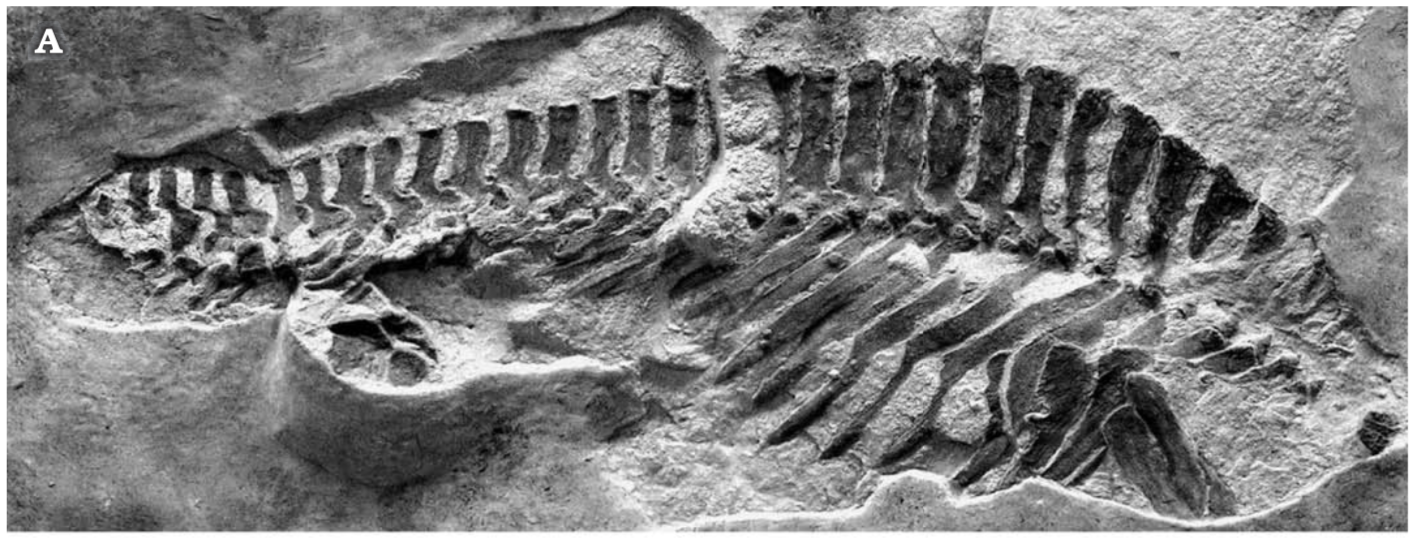

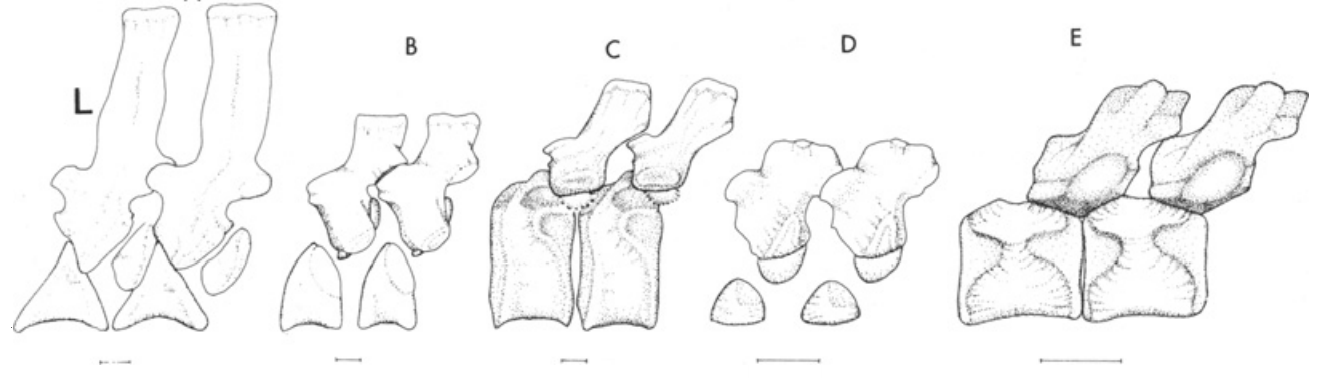

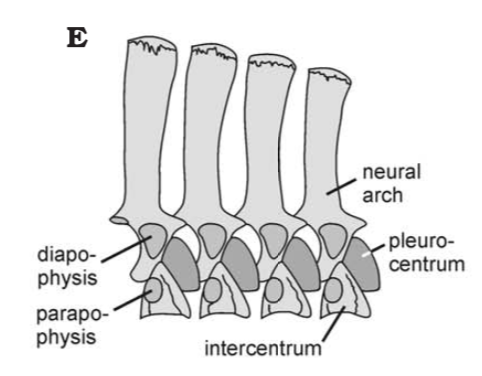

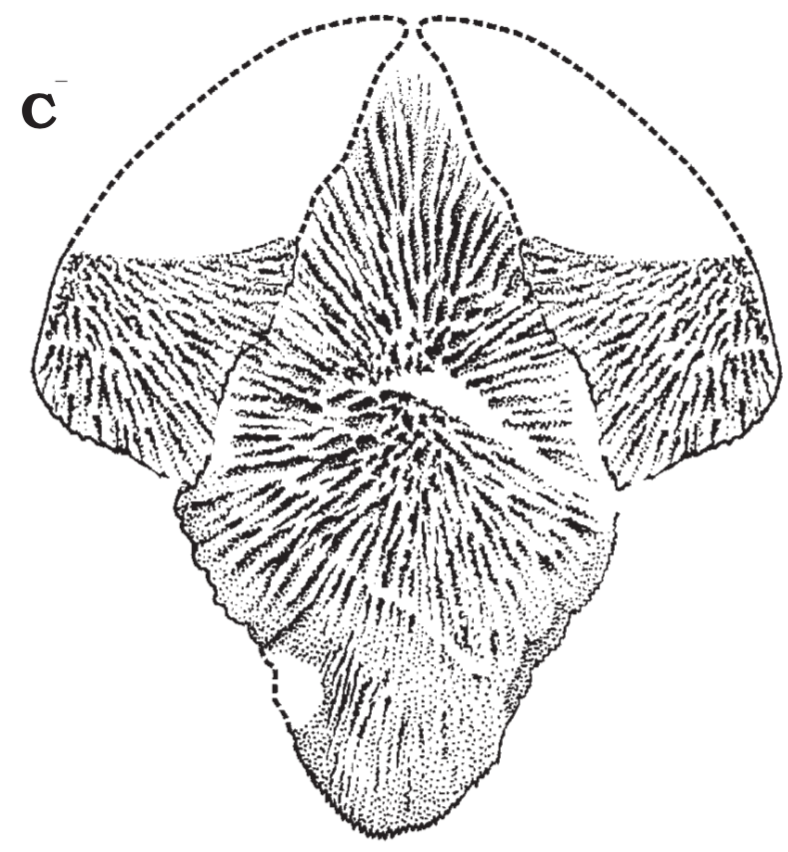

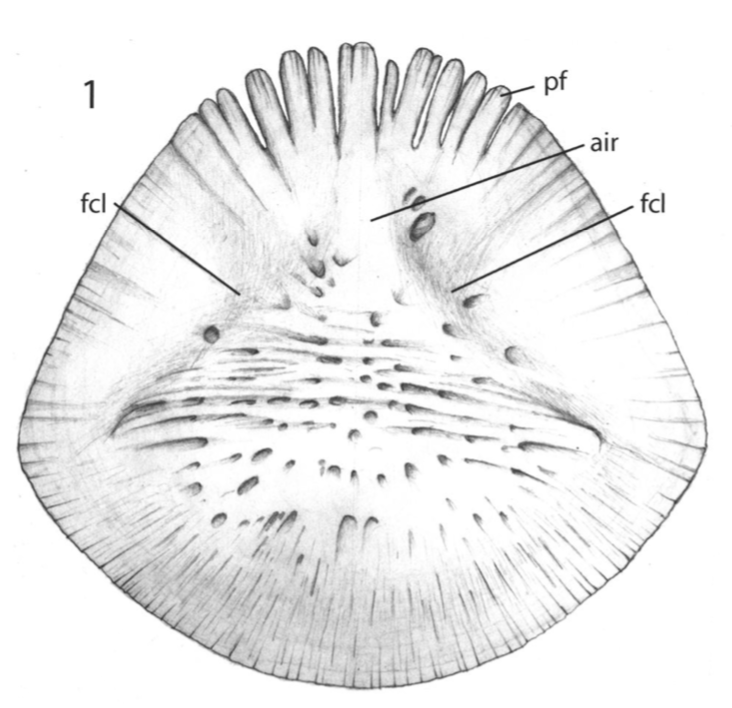

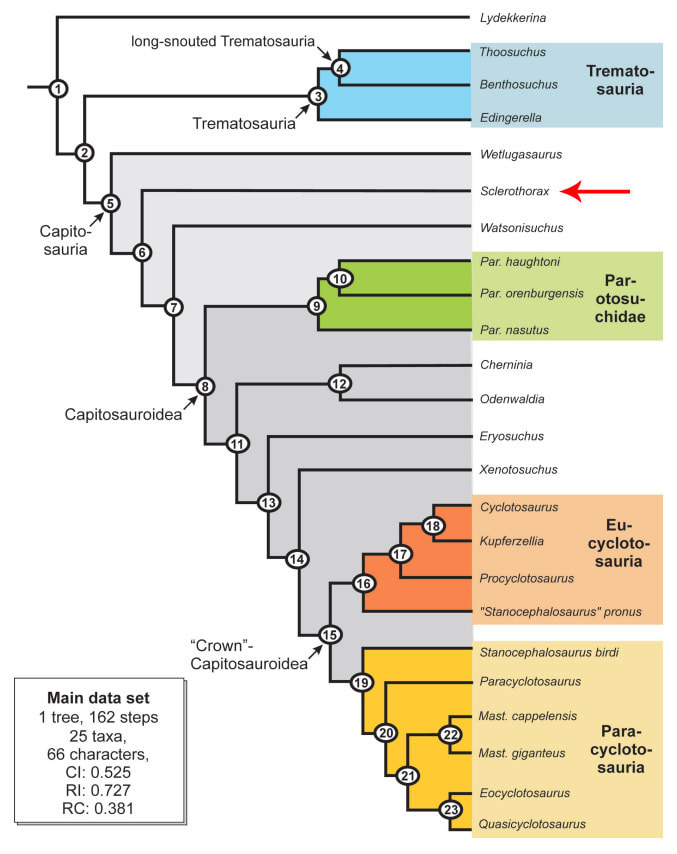

Cranial anatomy von Huene's original reconstruction wasn't that far off all things considered, and he got the general profile of the shape correct. The proportions (broad, short, and with a rounded parabolic snout) are not particularly close to any other temnospondyl, but the sutural patterns and the posterior skull conform very closely to those of capitosaurs. For example, comparing it with the early diverging capitosaur Wetlugasaurus (reconstruction from Schoch, 2008, below on left) reveals features such as an anteriorly extensive jugal ('j') that contributes to the orbital margin, a deep and well-defined otic notch with a well-developed tabular ('ta') horn, a disproportionately large prefrontal ('prf') in comparison to the postfrontal ('pf') and the postorbital ('po'), and a lateral (to the side) projection of the postorbital. Sclerothorax does have a frontal ('f') that enters the orbital margin; this isn't found in Wetlugasaurus, but it is found in many other capitosaurs. So in short, although the proportions run entirely counter to what every other capitosaur looks like, the sutural patterns are quite similar. This also holds true for the palate; although some features are extremely unusual for a capitosaur, such as a very broad cultriform process (shared with metoposaurids and brachyopids), the sutural patterns are again consistent Postcranial anatomy In contrast to the skull, the postcranial skeleton of Sclerothorax is far harder to corroborate with any stereospondyl. Arguably the most peculiar features of Sclerothorax are found in the axial column, such as its relatively elongate neural spines, which are more reminiscent of the condition seen in terrestrial Paleozoic temnos like eryopids and dissorophids than in stereospondyls, which often have poorly ossified and rarely preserved neural arches (compare the derived capitosaur Mastodonsaurus from Schoch, 1999, below on top with one of von Huene's specimens of Sclerothorax, below on bottom). The heightened spines throughout much of the axial column produce a distinctly hump-backed contour in contrast to the more or less consistently flat back seen in most Mesozoic temnospondyls. Another comparison below: on the bottom left is a figure from Warren & Snell's review of temnospondyl postcranial anatomy with Eryops (A), the capitosaur Parotosuchus (B), the metoposaurid Metoposaurus (C), the rhytidosteid Rewana (D), and the plagiosaurid Plagiosaurus (E); on the bottom right is the reconstruction of the vertebrae of Sclerothorax from Schoch et al. (2007). The pleurocentrum of Sclerothorax is also quite large for a stereospondyl; in many other groups, the pleurocentrum is entirely unossified or is at least distinctly smaller than the intercentrum.

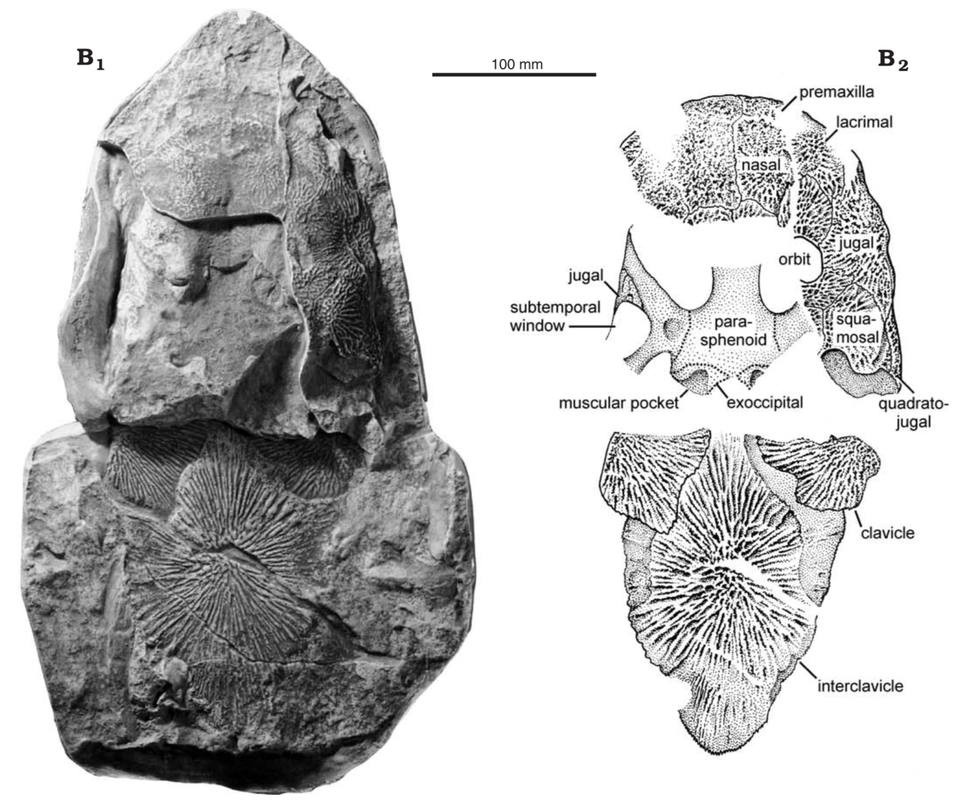

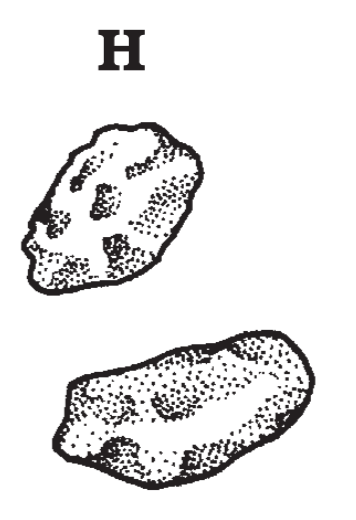

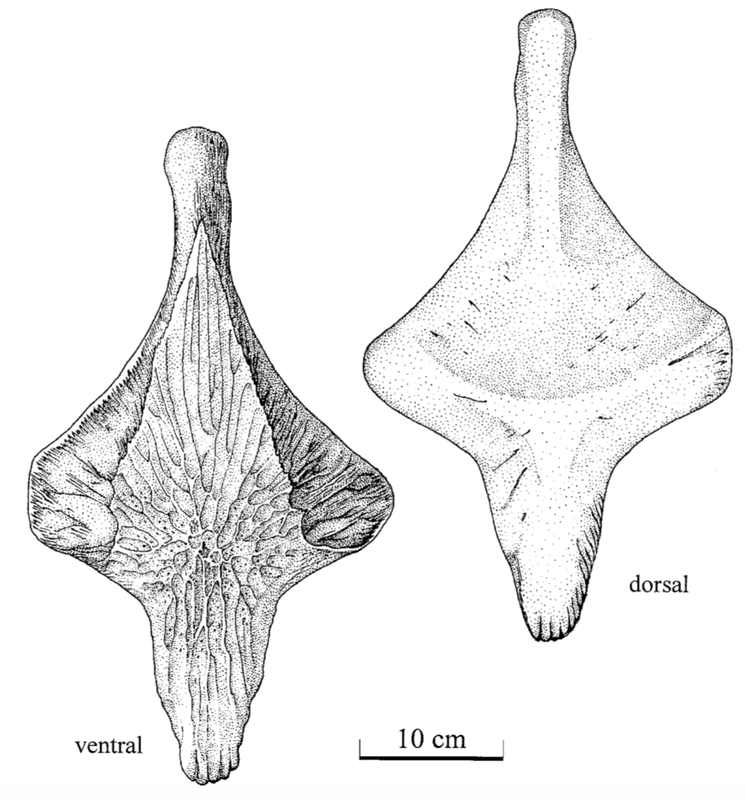

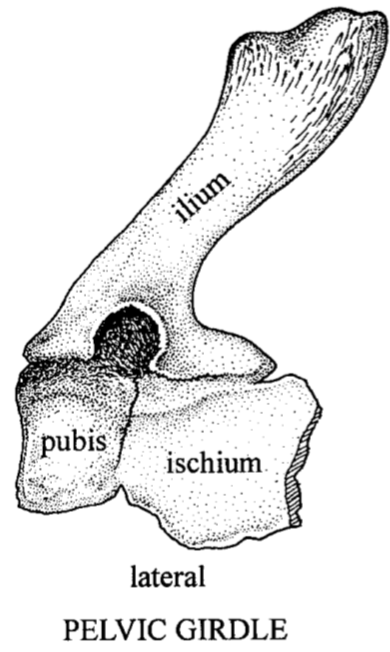

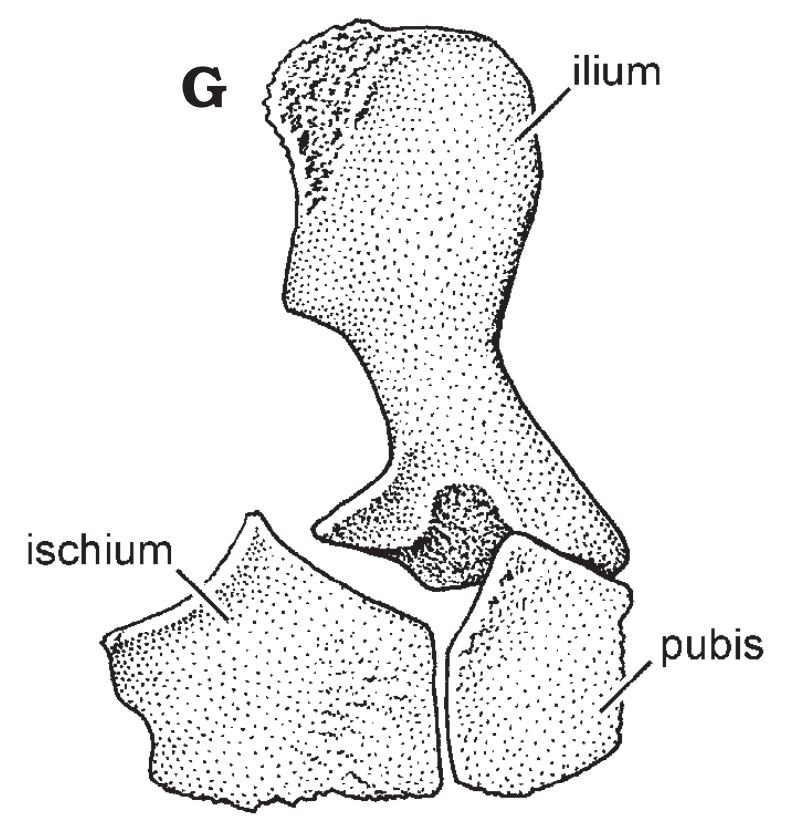

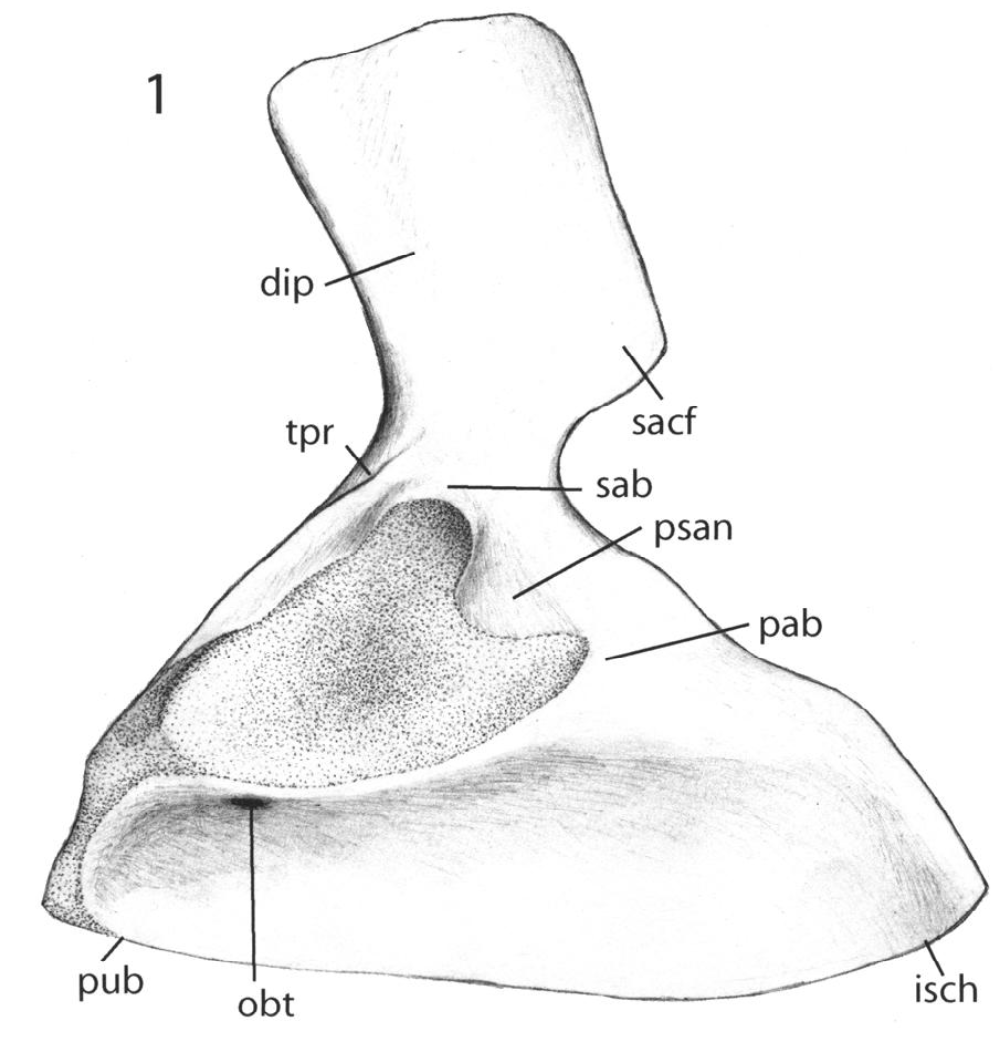

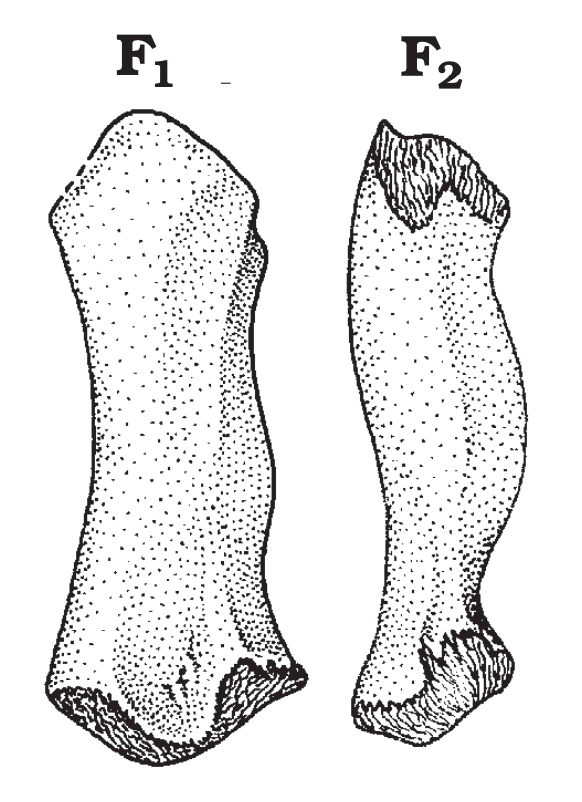

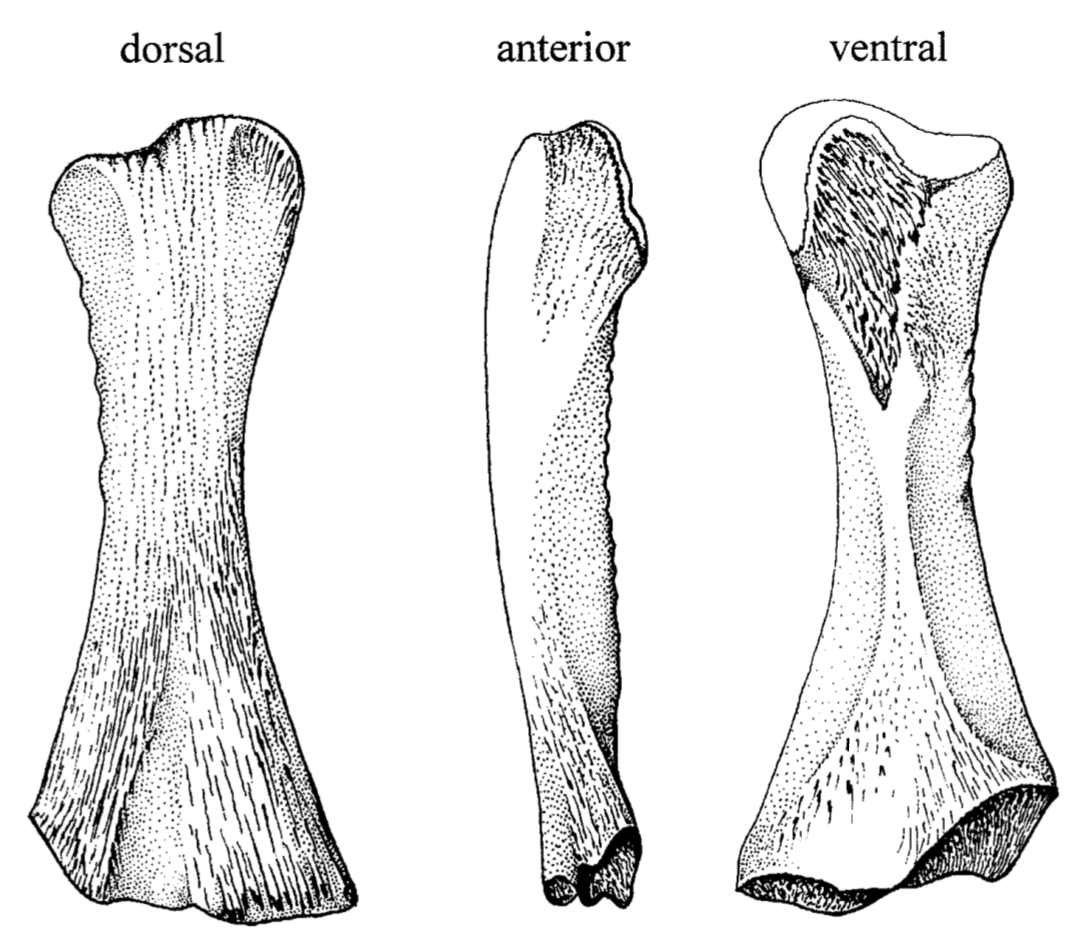

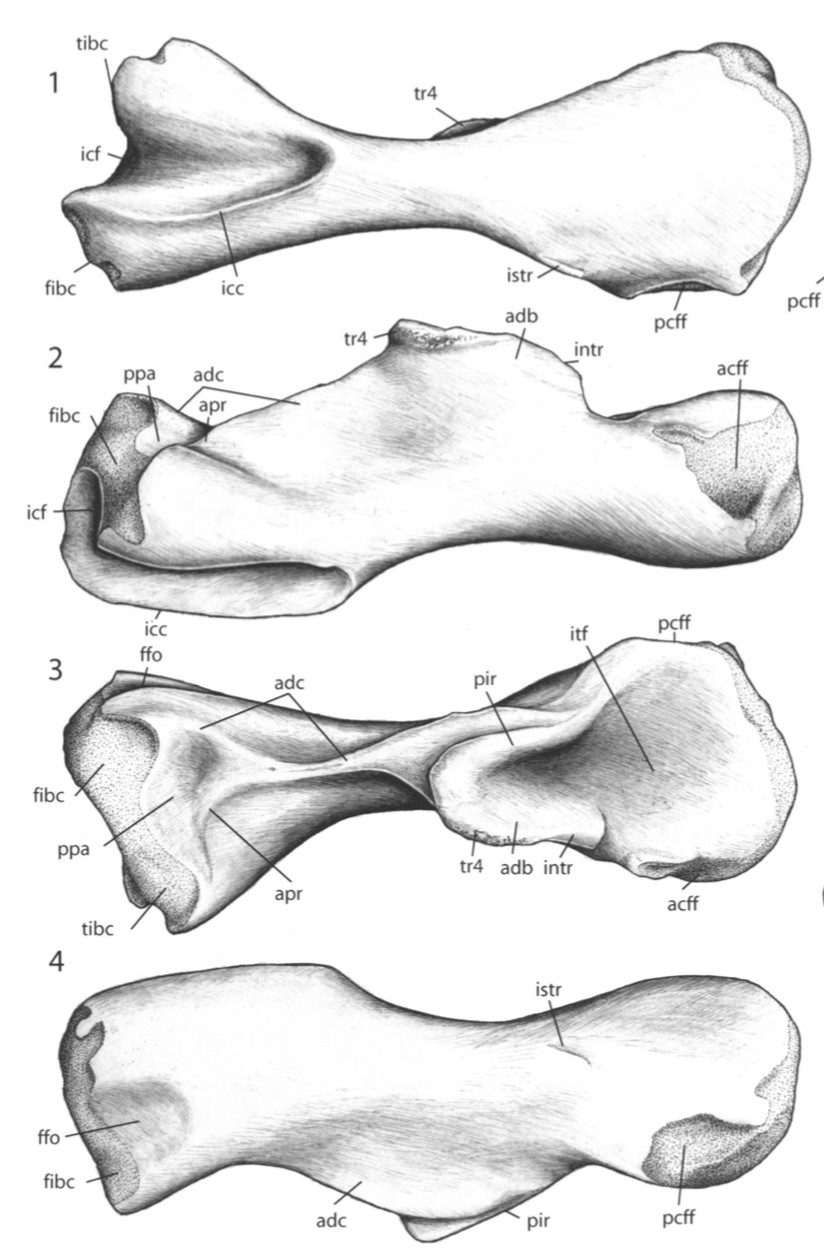

In spite of a number of features that are unusual for a stereospondyl, many of the features found in Sclerothorax do accord with the more typical stereospondyl anatomy. For example, the massive, ornamented pectoral girdle found in many Mesozoic stereospondyls is also found in Sclerothorax (below in middle) and compares favourably with that in other temnos (see Mastodonsaurus from Schoch, 1999, below on left) compared to terrestrial Paleozoic temnos like Eryops (below on right, from Pawley & Warren, 2006). Another example is the pelvis - well-ossified (i.e. all three elements are present) but with distinct sutures between all three elements (Mastodonsaurus from Schoch, 1999, below on left; Sclerothorax from Schoch et al., 2007, below in middle). Contrast this with the pelvis of Eryops (below on right; Pawley & Warren, 2006), which has a more developed ischium ('isch') and which lacks defined sutures between the various elements. It is worth pointing out, however, that the iliac blade (the vertically oriented part of the ilium) is broad and flat like what is found in more terrestrial temnospondyls, and there is a distinct projection ('sacf' in the Eryops pelvis on the right) that is not found in Mastodonsaurus. Comparisons of the femur also show more similarities to stereospondyls than to definitively terrestrial Paleozoic temnos like Eryops (below on right). The overall morphology and development of different features is similar to that of Mastodonsaurus (below on bottom left; Schoch, 1999), but it does have a more developed set of condyles for articulating with the lower leg, a well-developed adductor crest, and a bit of a curvature that are reminiscent of terrestrial temnospondyls.

Ecology of Sclerothorax Capitosaurs are regarded as classic examples of obligately aquatic, large-bodied temnospondyls, although histological work has suggested that at least some taxa could have been terrestrial (Mukherjee et al., 2010, 2019). Schoch et al. (2007) speculated that Sclerothorax was more terrestrially inclined than other capitosaurs based on the more unique postcranial attributes but also noted the development of lateral line grooves suggested that it could not have been fully terrestrial. Of course, these things are more gradational than black-and-white; often we tend to frame things as being rather binary. Dissorophids are a good example of highly terrestrial temnospondyls, while metoposaurids are a good example of undoubtedly waterbound temnospondyls, but like modern amphibians, at least some temnospondyls were probably quite capable of being amphibious and moving across the land-water interface at will or at least on a need-to-find-a-new-pond basis. Typically, paleontologists have relied on the external features of the skeleton as a guide for inferring the ecology of extinct tetrapods, but it gets complicated when a particular clade undergoes a shift in ecology, such as terrestrial to aquatic or diurnal to nocturnal. Those changes don't happen overnight, and so an animal with a leaning toward one ecology may still largely reflect the differing ecology of its ancestry. Doing comparative histology is certainly one way to approach the question in a different fashion, but development and microanatomy can be similarly constrained by phylogeny in the same way that the external anatomy can be, so it can still produce conflicting results. Capitosaur phylogeny (with Sclerothorax) suggests that capitosaurs were primitively aquatic, so any terrestrial adaptations acquired by Sclerothorax would have been secondarily acquired; this could explain why it converges on some morphologies found in Paleozoic taxa like Eryops or dissorophids but with many features that are found in more unequivocally aquatic stereospondys. I like to equivocate personally, so I'd like to think that Sclerothorax is somewhere in the middle, probably hanging out in water for most of the time but probably capable of moving around only partially submerged near the shore and moving between bodies of water as necessary. Refs

Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed