Mesozoic temnospondyls

|

|

Perhaps equally, if not more, peculiar than Paleozoic temnospondyls are their Mesozoic cousins. These were predominantly large (often 2+ meters), fully aquatic taxa that roamed freshwater (and perhaps a few marine) environments, vacuuming up whatever could fit in their mouths.

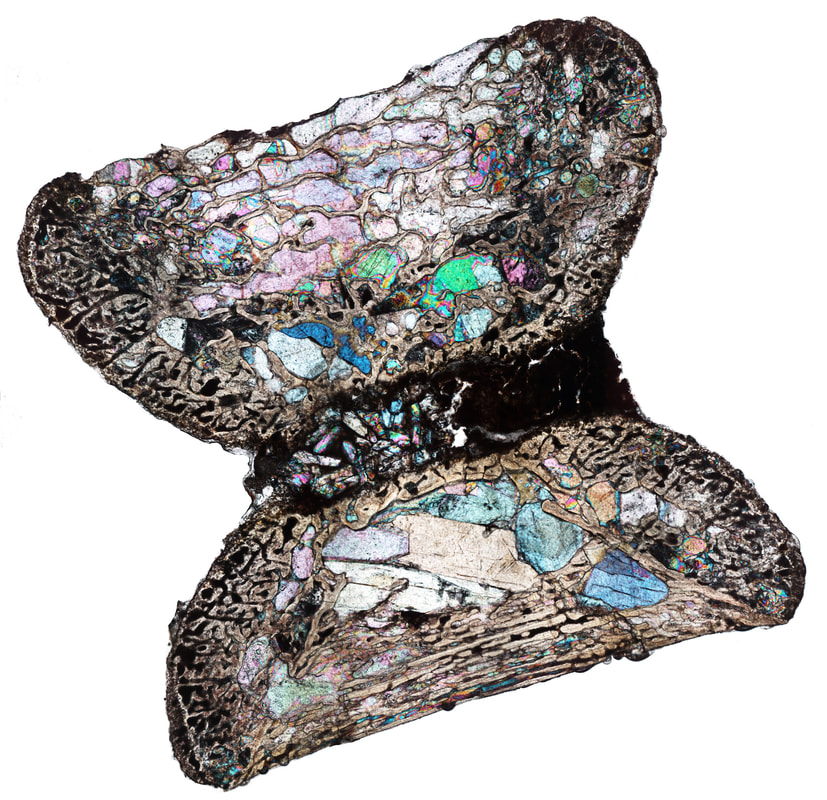

Most of my research on Mesozoic temnospondyls is related to a group known as metoposaurids, which were widely distributed across what was then (and mostly now) the northern hemisphere - North America, northern Africa, western Europe, and India. Like many other temnospondyls of their time, they had mostly flat skulls and probably raised their head (like a toilet seat) rather than lowering their jaws (like most other vertebrates) to open their mouths. They were probably ambush predators that lurked on the bottom of rivers and lakes, waiting for fish and other animals to swim overhead (think like a flounder). Metoposaurids are incredibly abundant components of Late Triassic ecosystems, and in North America, they are the only large temnospondyl known from the entire time period (excepting a single jaw of a close relative). Often times, they are preserved in mass assemblages with dozens of individuals, representing some combination of ecological and environmental factors that led to their post-mortem aggregation. Metoposaurids are unusual among temnospondyls (and other tetrapods in general) in being very morphologically conserved - that is to say that all of the known species are quite similar to each other, more so than is seen in other groups. As a result, elucidating their evolutionary relationships remains an ongoing challenge because of the absence of a large number of features by which to differentiate them. Most of my work to date has been addressing a proposed trend of size reduction in metoposaurids (in a taxon called Apachesaurus) using bone histology, which so far has yielded a lot of evidence that it is simply a juvenile of a typically large taxon, not a smaller species. |