|

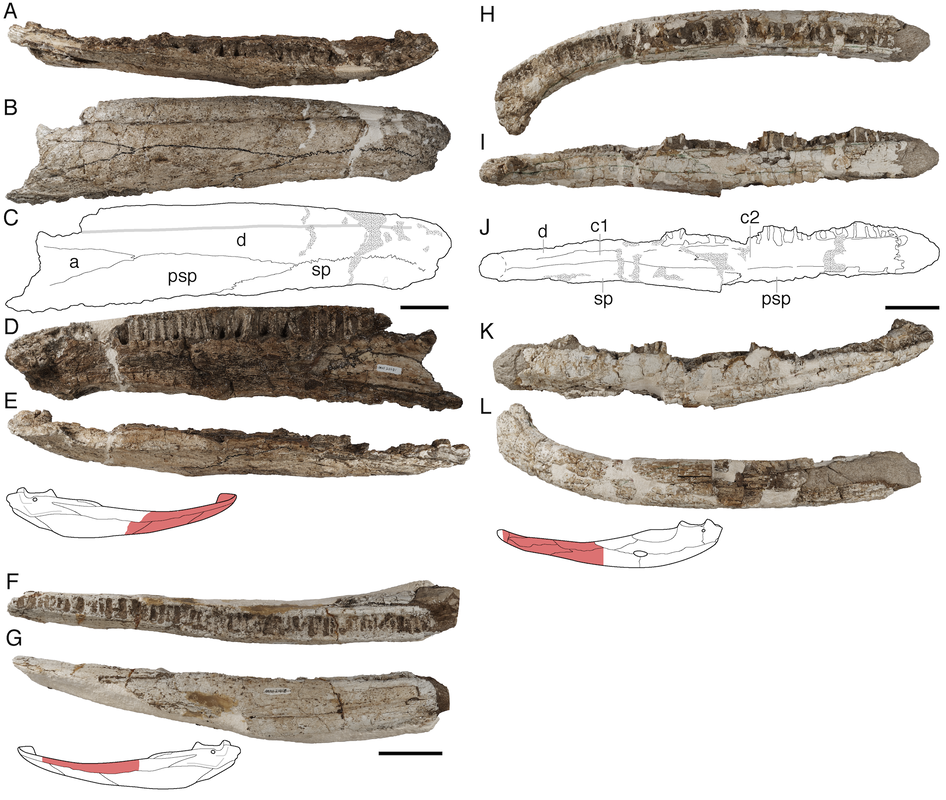

Title: Cold capitosaurs and polar plagiosaurs: new temnospondyl records from the upper Fremouw Formation (Middle Triassic) of Antarctica Authors: B.M. Gee; C.A. Sidor Journal: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2021.1998086 General summary: The Middle Triassic captures a diverse global record of temnospondyls, which is also when we start to see the pinnacle of the evolution of large body size, with many taxa routinely exceeding skull lengths of half a meter and body lengths of probably 2m or greater. A variety of different groups are present at this time, all of which appeared in the Early Triassic and which would also continue through the Late Triassic, and many ecosystems were host to several different species of no close relatedness. However, the Antarctic record of Middle Triassic temnospondyls has only comprised members of a single clade, the capitosaurs. Dated and brief historical notes suggested the possible presence of another clade, the long-snouted crocodilian-like trematosaurs, but this was never substantiated, and thus the Antarctic record, despite preserving at least three different species, captures an overall much lower diversity of temnospondyls than found elsewhere around the world. In this study, we took a look at some of this more ambiguous historical material, combined with more recently collected material of some very large lower jaws. While every single one of these lower jaws belongs to a capitosaur, there is a partial interclavicle (part of the shoulder girdle) that is very clearly not that of a capitosaur but instead that of a plagiosaurid, a peculiar short-snouted clade that has hundreds of records from the northern hemisphere but a mere two others from the southern hemisphere (both of those are from the Early Triassic). We speculate on some of the reasons why the Antarctic record, which is undoubtedly undersampled, might reflect real patterns of differing ecologies among large-bodied temnospondyls (i.e. 'big crocodile analogue' is a gross oversimplication).

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed