|

Title: Size matters: the effects of ontogenetic disparity on the phylogeny of Trematopidae (Amphibia: Temnospondyli) Authors: B.M. Gee Journal: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, no. 170 (Advance Articles) DOI to paper: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz170 General summary: Phylogenies represent our inference of the relationships between different organisms, and can be as broad-scale as all living things to as fine scale as species of rhinos. It is of course an inference because in very few instances can be observe or capture speciation in short time intervals, and reconstructing the relationships of long-extinct taxa, especially those without close living relatives, is even more complicated. Phylogenies are therefore very controversial because there are a slew of different ways that one can go about doing one, and different scientists have different preferences. Which taxa are included, which features are analyzed, and how each taxon is "scored" for each feature can vary widely across studies, which unsurprisingly produces very different results and in turn, very different scenarios of evolutionary history (e.g., temporal origin, rates of diversification, geographic origin, relation to modern taxa, etc.). The hot topic in early tetrapod research right now is early amniote phylogeny, particularly with respect to parareptiles, 'microsaurs,' and varanopids. That doesn't mean that there isn't a lot of work to do with temnospondyls though, which of course is what this paper is about!

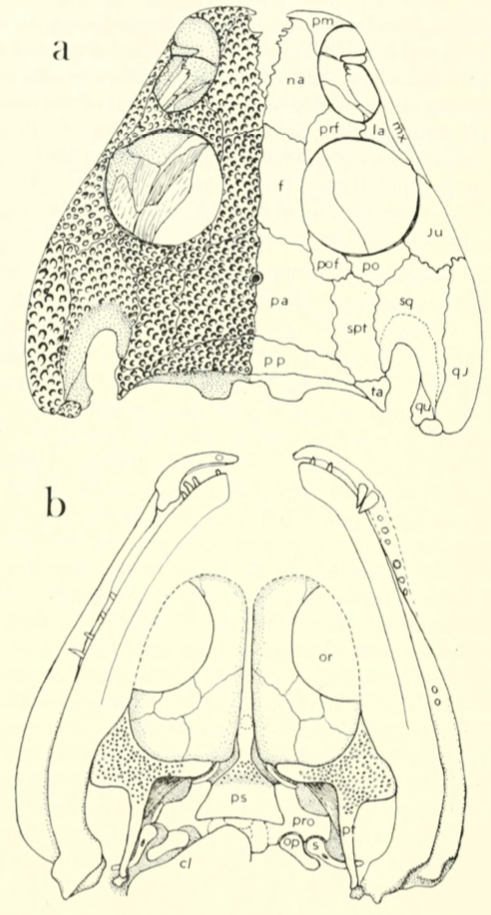

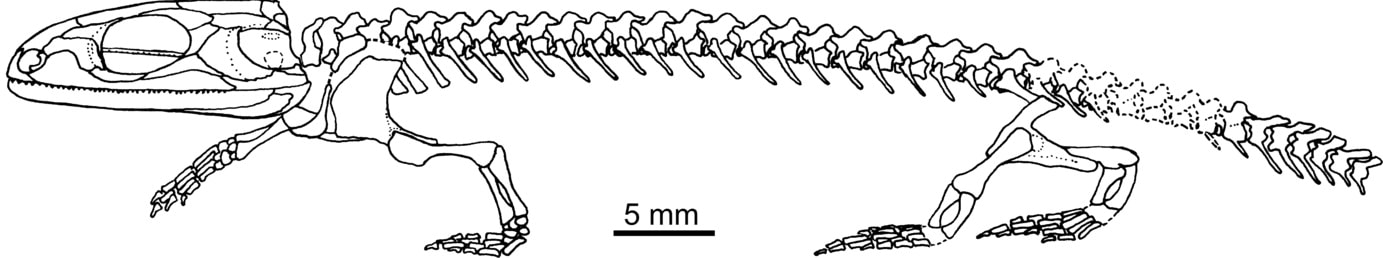

Title: A re‐description of the late Carboniferous trematopid Actiobates peabodyi from Garnett, Kansas Authors: B.M. Gee, R.R. Reisz Journal: Anatomical Record DOI to paper: 10.1002/ar.24381

Note: This was supposed to be out last week, but then the Kobe Bryant tragedy happened, and as a native Angeleno, that was a lot to deal with, so I put the post off to this week. The Land That Time Forgot is a classic 1918 trilogy (technically combined into a single volume in 1924 and itself part of the Caspak trilogy) in which a hardy bunch of Americans and Brits hijack a U-boat in the middle of WWI and find themselves in a weird island with a bunch of prehistoric creatures including various purported stages of human evolution living as distinct tribes. The trailer for the 1975 movie tells you that you can learn the "secrets of evolution." I have never seen the movie, but since I liked The Valley of Gwangi, which I watched on a mobile projector displayed on a bedsheet draped over the soccer mom van of the education department of the LACM, I am sure that it is of high cinematic quality in spite of its Rotten Tomatoes rating. These movies capture a certain affinity for the notion that pockets of animals thought to be long-extinct might exist, and indeed there are various cryptozoological monsters themed around this, like the mokele-mbembe, based on the notion of a sauropod-like beast living in the depths of the jungles of the Congo. For some reason, nobody's ever come up with a cryptozoological creation based on a temnospondyl, which seems like a real missed opportunity to put a 3-meter amphibian in the Mississippi River, and I am not proposing one now, although as I have told some people in person, I am amenable to the idea of donning a temnospondyl body suit and cruising around a body of water.

Temnospondyls are not forgotten by time - if anything, they are just forgotten, period - but there are a few records of lineages where one taxon shows up way after its compatriots were thought to have kicked the can. We call these "relict taxa," a name obviously referring to the remnant of something much more common or widespread in earlier days (which were usually better days if you were a temnospondyl, back when the world was warm and humid and probably humming with crunchy invertebrates). Edopoids, already regarded as one of the more primitive temnospondyl groups, are one of the few for which a relict taxon is known: Nigerpeton, aptly named for Niger from which it is known. |

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed