|

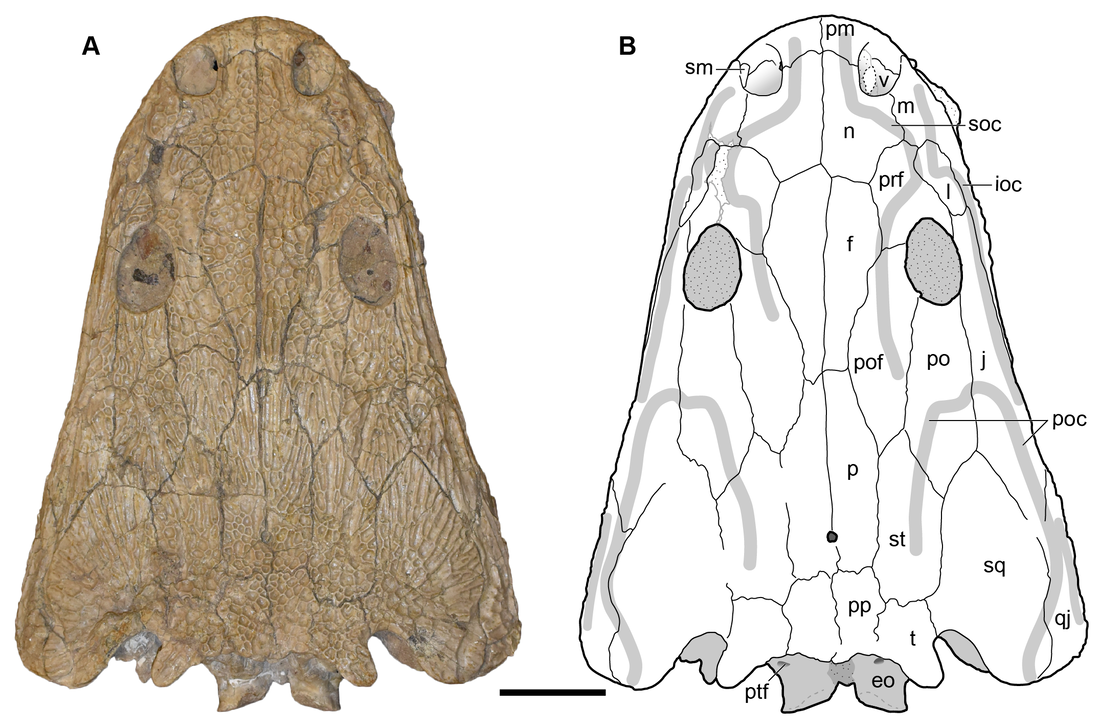

Title: Revision of the Late Triassic metoposaurid “Metoposaurus” bakeri (Amphibia: Temnospondyli) from Texas, USA and a phylogenetic analysis of the Metoposauridae Authors: B.M. Gee; A.M. Kufner Journal: PeerJ DOI: 10.7717/peerj.14065 General summary: Frequent readers of this blog are of course familiar with my love for metoposaurids, one of the most iconic groups of North American temnospondyls. It is no secret that metoposaurids were my "gateway drug" to the world of terrifyingly large and unrecognizable amphibians, and so they always have a special place in my heart. My previous research has largely focused on two of the three species, Anaschisma browni (ex. Koskinonodon perfectus, ex. Buettneria perfecta) and Apachesaurus gregorii, which are the two most common metoposaurids that we get in the Late Triassic of North America. If you go to a museum and see a metoposaurid (most major museums in the U.S. have a metoposaurid on display), it's likely Anaschisma browni, although the label may be two or three junior synonyms out of date. The third species, known only from two sites in Texas and one site in Nova Scotia, doesn't get as much press - it was last (re)described in 1932! Ninety years later, my buddy Aaron Kufner and I are pleased to produce a full redescription of this taxon, long referred to as 'Metoposaurus' bakeri, based on a reexamination of material from the type locality that now lives at the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology (UMMP) collections in Ann Arbor. With a thorough redescription spanning 134 print pages (probably too thorough, even by my own standards), we provide extensive documentation of the skeletal anatomy of this species (1930s-era drawings have their limitations), conducted more phylogenetics analyses to test the relationships of metoposaurids (this has gotten no better since the 1930s), and ultimately concluded that this species cannot be placed in an existing genus like Metoposaurus (otherwise only known from Europe). To that end, we created a new genus name, the mouthful Buettnererpeton, which honors a longtime fossil preparator at the UMMP, William H. Buettner, who worked extensively with E.C. Case, the museum curator who named the species in 1931. The suffix comes from -herpeton, meaning 'creeping animal' in Greek, which is a common component of names of early reptiles and amphibians. Our taxonomic act has implications for biostratigraphy (relating distantly situated rocks based on which taxa occur in them), both globally and within North America, and we discuss everything from future work needed on metoposaurids to why their phylogenetic relationships are so badly resolved. This is a 'boundary-crossing' project that originated when I was a Ph.D. student in the summer of 2019 and has only now made it to the finish line, so it is particularly memorable for me in that regard.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed