|

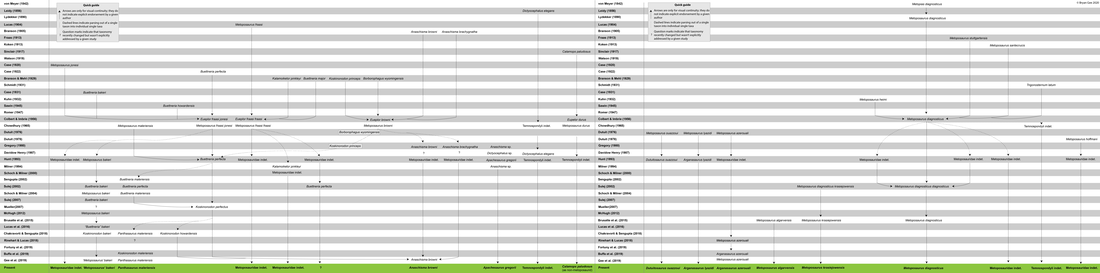

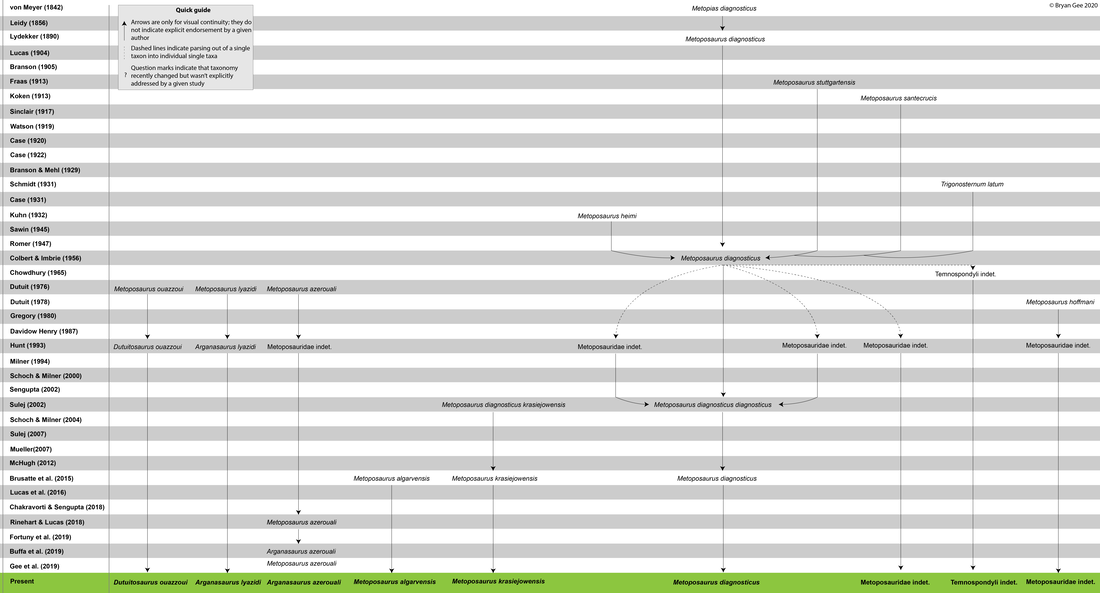

Having finished writing my thesis, I've been finding some weird ways to keep myself busy, and I spent all of yesterday putting together a genealogy of metoposaurid taxonomy over the years! This isn't really a blog post, but I may do a couple more of these in the next couple weeks on things that actually on groups that are related to my dissertation. Metoposaurid taxonomy is very complicated, and there's also this prevalence of subspecies concepts being used for them, so my goal was to make a visual that could be a useful guide for people who don't have it all memorized in their head like me! The full version is above, but as you can probably tell, you can't read anything because the entire image is 1.5 meters long (no typo) even though I'm using a pretty small font size. I think my website builder downsamples images when it uploads them, so you can find the full version here! This is still a WIP (and hypothetically I might use it myself for something at one point), so please do not use this without asking me first! This is the right half of the diagram, which is maybe marginally more readable than the full version (and also the way less complicated side of the diagram).

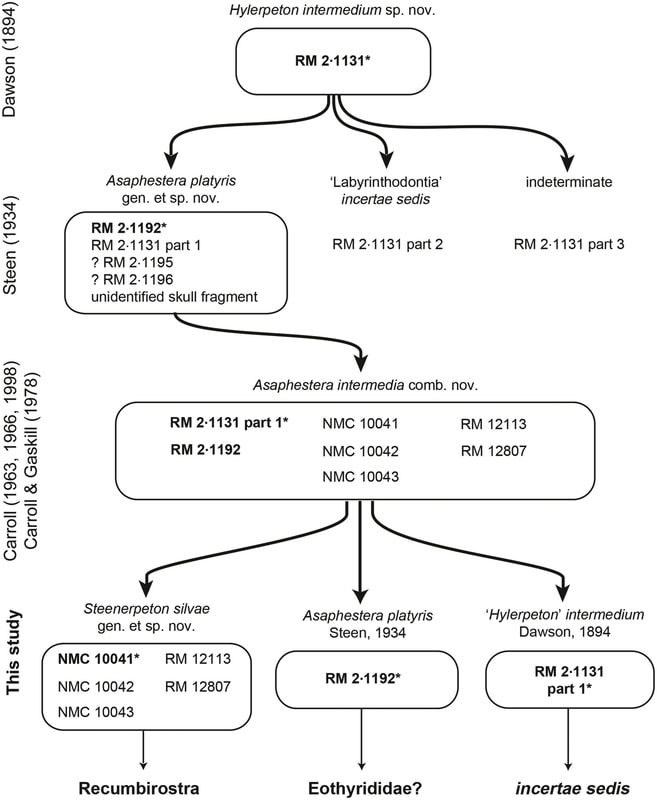

Title: Reassessment of historic ‘microsaurs’ from Joggins, Nova Scotia, reveals hidden diversity in the earliest amniote ecosystem Authors: A. Mann; B.M. Gee, J.D. Pardo, D. Marjanović, G.R. Adams, A.S. Calthorpe, H.C. Maddin, J.S. Anderson Journal: Papers in Palaeontology DOI to paper: 10.1002/spp2.1316 General summary: In what is my biggest collaboration to date with nearly all of the early tetrapod workers in Canada, here's probably my last paper of 2020: a very thorough revision of the 'microsaur' Asaphestera from Joggins, Nova Scotia! Joggins is one of the oldest sites with a well-preserved late Carboniferous tetrapod community (315-318 Ma), and it preserves a unique forest swamp environment in which animals are frequently preserved inside of logs (whether or not they lived in the logs is another question). Because of its age, Joggins is critical for exploring the early origins of many groups, as it often preserves the oldest members of many Paleozoic clades in North America, if not globally. For example, the temnospondyl Dendrerpeton from Joggins is the oldest known temnospondyl on the continent. There's a rich suite of 'microsaurs,' the ever controversial group of tetrapods of unclear affinities to either crown reptiles or to crown amphibians, that have been reported from Joggins, but many of the original studies are dated such that the interpretations are of limited utility for modern workers trying to elucidate phylogenetic relationships and other macroevolutionary trends. The frequent disarticulation and fragmentation of specimens also makes referrals of specimens to the same taxon somewhat suspect, with the potential for purportedly well-known taxa to be represented by a chimeric blend of multiple taxa. We spent a lot of time looking at historic specimens of one such 'microsaur,' Asaphestera, because we were particularly interested in exploring some of these very poorly known Carboniferous 'microsaurs' that are really important for understanding the evolution and relationships of the much better known early Permian taxa that everybody on this paper has studied to various degrees. Through this, we identified that the various specimens lumped under Asaphestera intermedia are actually a hodge-podge of different taxa, at least one of which is not even a 'microsaur,' but as we propose, is perhaps the earliest definitive synapsid! The oldest synapsid?

Microsaur math

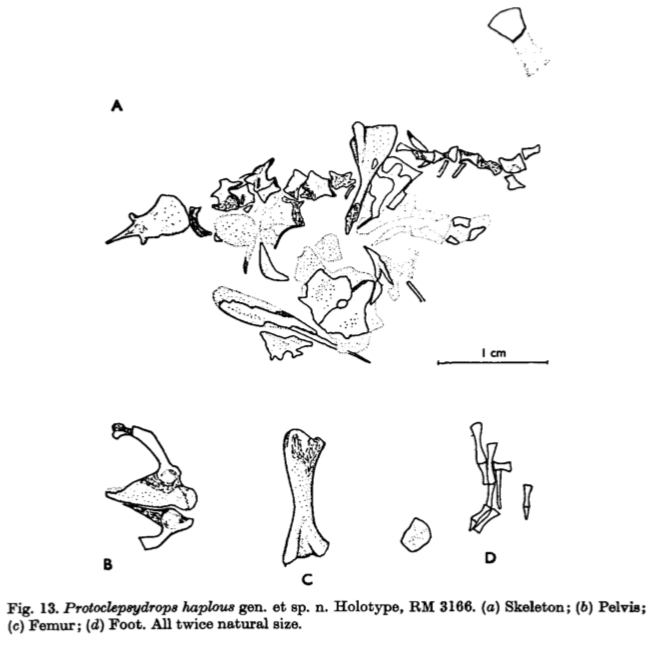

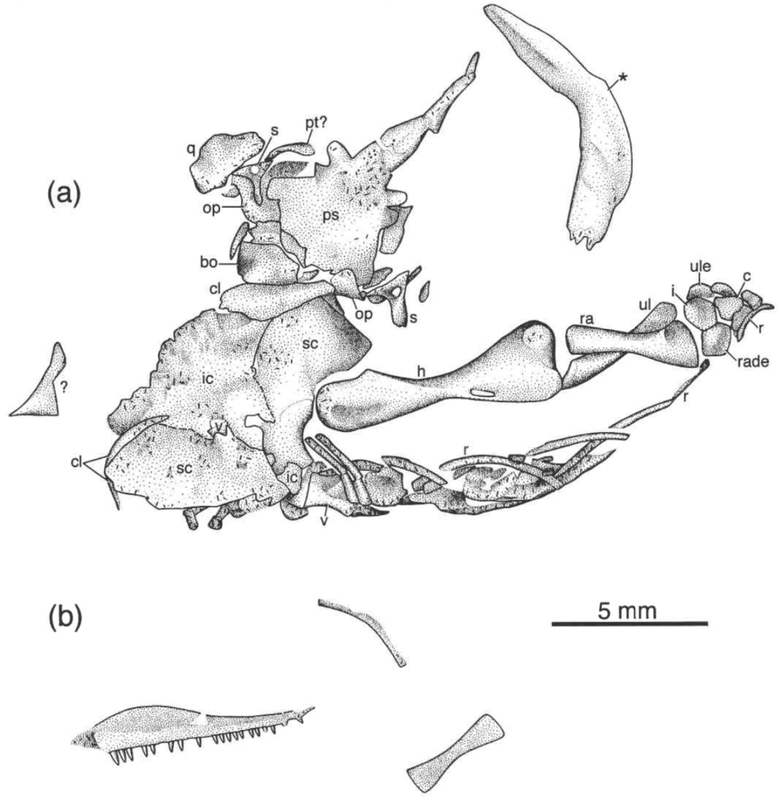

RM 2-1131 was the original holotype of Hylerpeton intermedium and became the holotype of the new Asaphestera intermedia. Here it is above on the right. If the figure does not look that impressive...that's because the specimen is not very impressive. We couldn't identify it to a particular tetrapod clade, let alone diagnose it as a unique taxon of whatever clade that might be, and we designated it as a nomen dubium ("doubtful name"), which is the fancy way of saying "this is not valid because it is not clearly unique." So at this point, we've killed one 'microsaur.' Net: -1 microsaur

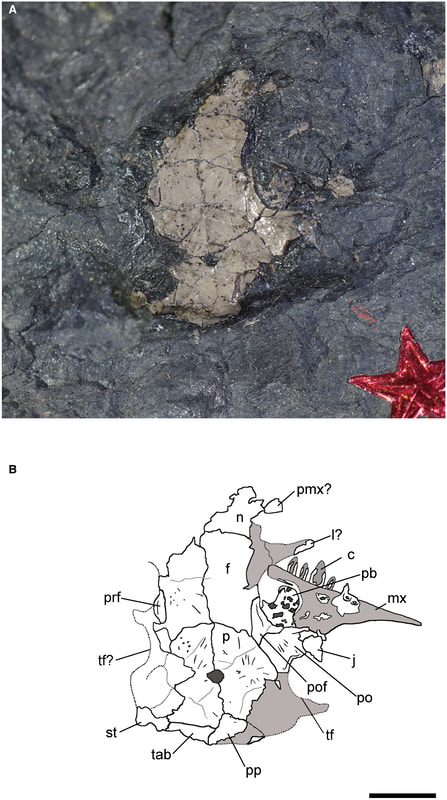

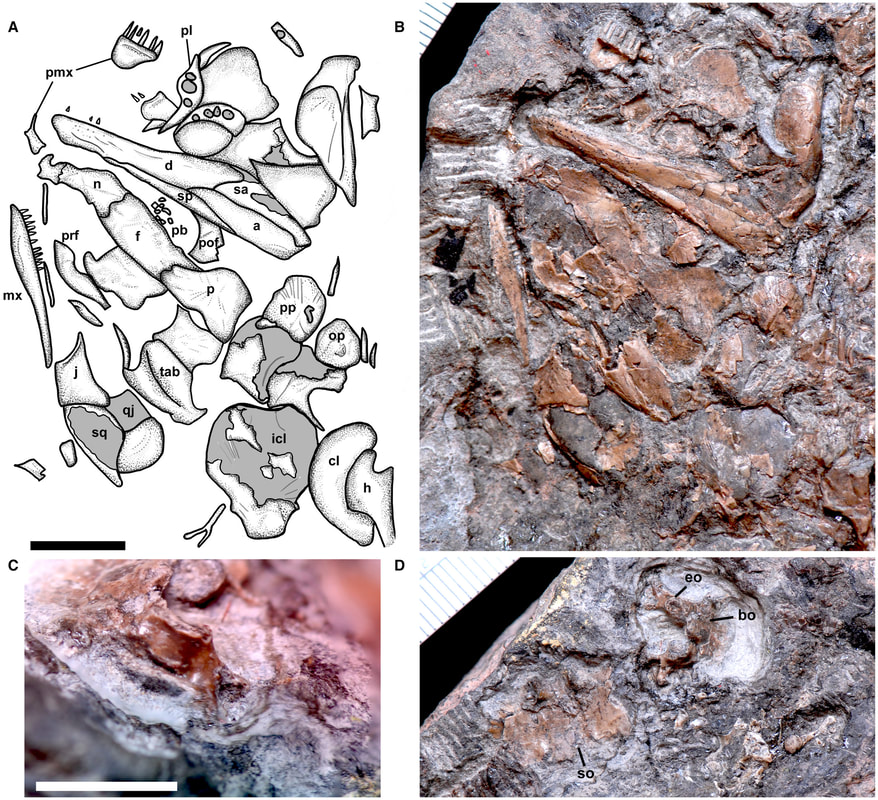

In any event, we then set about examining the referred specimens of "Asaphestera intermedia," at this point a sunk taxon, because some of them are much nicer. The one above was sufficiently complete to be diagnosed and differentiated from other taxa, and we made it a holotype of a new 'microsaur' taxon: Steenerpeton silvae, which we named for Margaret Steen, (the same Steen I keep mentioning throughout this post), and for 'of the forest,' referring to Joggins original paleoenvironment. So now we've added back one 'microsaur!' Net: +0 microsaurs Steenerpeton appears fairly derived already, in contrast to traditional interpretations of Asaphestera of any flavour, and we suggest that it may be a recumbirostran, the derived group of 'microsaurs' that host a suite of fossorial adaptations. This actually lines up well with the documented presence of other derived 'microsaurs' like possible pantylids and gymnarthrids at Joggins and provides more evidence that the origin and diversification of recumbirostrans begin earlier than has been historically conceived and probably occurred in an interval without substantial body fossils. The former point in particular is a real running theme at this point for most of the research that all of us do.

Avengers assemble!This is the biggest collaboration I've ever worked on (some might say the most ambitious crossover ever). It was born nearly 2.5 years ago at the SVP Annual Meeting in Calgary, which is where Arjan and I both gave talks on different 'microsaurs' (Arjan's turned into his published paper on the new Mazon Creek 'microsaur' Diabloroter, and mine turned into my published paper on new material of Llistrofus from Richards Spur). Jason Pardo (and Jason Anderson) had just had a high-profile paper come out that summer that recovered 'microsaurs' as crown amniotes, a paper I didn't stop hearing about from my advisor even though I spent the whole summer doing fieldwork in Arizona. We all ended up talking about future directions for 'microsaur' work and agreed on needing to reevaluate a lot of the earliest records of what are called "tuditanomorphs" to better characterize them for big tetrapod analyses to continue to sort out different relationships. This in turn spawned what's become a dynamic working group among the three of us and eventually led to us jokingly assigning ourselves as different members of the Avengers as this team of early career researchers doing early tetrapod work on basically every single clade that's out there. If you add up everything that we've collectively published, we account for actinopterygian and sarcopterygian fish, aïstopods (stem tetrapods), temnospondyls, parareptiles, seymouriamorphs, embolomeres, synapsids, and 'microsaurs.' You can see some of the other fruits of this working group in Pardo & Mann (2018), Mann, Pardo & Maddin (2019) and Mann & Gee (2020), with plenty of future work slated for the immediate future (or once things sort of go back to normal)! I will leave it to the readers' imagination as to which members we have self-assigned as... The final sumThe Joggins 'microsaurs' are the only taxa from Carboniferous localities that have experienced these sorts of "lump/split" boom-bust cycles, going from being remarkably taxonomically diverse to remarkably intraspecific variable and back again. The classic Joggins temnospondyl, Dendrerpeton, is another great example of this; the type species, D. acadianum, includes several defunct genera such as Smilerpeton (great name) and Dendryazousa. There are numerous taxa that have been named that weren't even assigned to the correct clade! A lot of this has been because of historic interpretations based on the often fragmentary and disarticulated specimens at Joggins; we don't get many 3-D specimens, and the distortions can affect interpretations of the anatomy. This means that there's a lot of room to go back and look at specimens that were often collected more than 120 years ago and that haven't been re-examined in detail in more than 60, 70, 80... years to assess the original interpretations. Particularly in light of new discoveries at other localities, updated taxonomy, and the recognition that a lot of clades have deeper origins than was often hypothesized in the early 20th century, exploring one of the oldest (crown) tetrapod assemblages in the world is essential for unraveling a lot of the mysteries of the origin of the modern tetrapod clades. When we started this project, there were seven 'microsaurs' recognized from Joggins: Archerpeton, Asaphestera, Hylerpeton, Leiocephalikon, Ricnodon, and Trachystegos. We added Steenerpeton (total: 8), but deep-sixed Archerpeton, recognized Asaphestera proper as a synapsid, and cast doubt on the Joggins records of Ricnodon (final count: 5). We've got plans for some of those other ones that didn't get addressed here...stay tuned for plenty more studies coming out on Joggins material and other Carboniferous faunas! Refs

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed