|

"The labyrinthodonts" might sound like the name of one of those weird fantasy monsters from Pan's Labyrinth, but it's actually a widely used (and nowadays disused) scientific term that refers to a large grouping of early tetrapods. Anyone perusing classical literature may notice that this term often comes up a lot more than 'temnospondyl' (in addition to other terms like 'batrachomorph'). But the name is pretty rare outside of the scientific literature, so what's it mean?

The oldest reference that I can find of the term 'labyrinthodont' is a publication by von Meyer in 1842. It was quickly picked up by other workers (e.g., Burmeister, 1849) before being formalized as the name of a taxonomic group by Owen (1860). The name derives first from the temnospondyl genus Labyrinthodon, which is no longer a valid name (being a junior synonym of Mastodonsaurus). This in turn derives from the labyrinthine (resembling a labyrinth or maze) structure of the teeth that was recognized quite early on in the general history of paleontology (1830s), let alone the study of temnospondyls. The term has largely fallen out of favour with respect to taxonomy (discussed below), although it still occurs sporadically throughout the literature in the 21st century (e.g., Martin & Merriam, 2011; Pledge, 2013) and remains widely used to describe the tooth structure that gave the group its name. During last week's cold snap, I covered the temnospondyls from the South Pole. This week is covering the temnospondyls from the North Pole! Particularly appropriate after this part of North America got buried by a giant snowstorm last night. As with Antarctica, the modern-day Arctic isn't exactly the most hospitable area for amphibians (although there are a few species that live there today), but it was evidently a much nicer place to live 250 million years ago. The temnospondyl record in the Arctic is primarily confined to Greenland and Norway (and that's all I'm covering here), which were also home to a substantial number of important fish and early tetrapod taxa (e.g., Acanthostega from Greenland) during earlier geologic periods. Some of the northern regions of Russia are of a comparable paleolatitude but will be covered in future post(s) once I track down more literature / translations.

P.S. some of this week's images are not exactly high-quality because they're phone pictures of print copies that are too fragile to be scanned / my university's closed until noon today anyway, so I don't have a scanner even if I wanted one. New publication: CT data on the 'microsaur' Llistrofus (Gee, Bevitt, Garbe, & Reisz, 2019; PeerJ)1/25/2019

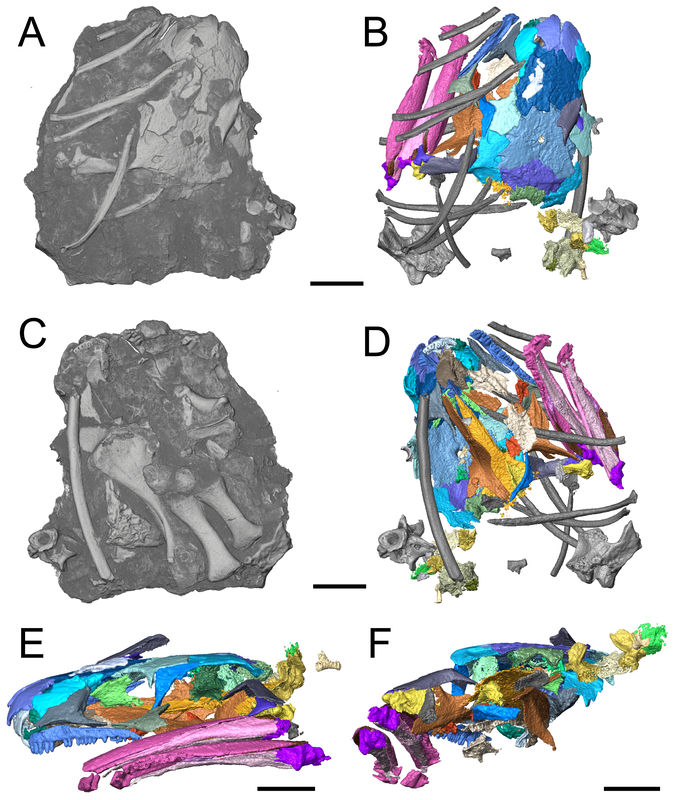

Title: New material of the ‘microsaur’ Llistrofus from the cave deposits of Richards Spur, Oklahoma and the paleoecology of the Hapsidopareiidae. Authors: B.M. Gee, J.J. Bevitt, U. Garbe, R.R. Reisz Journal: PeerJ, vol. 7, article #6327 Link to paper - this is an open access paper that can be viewed by anyone! Antarctica todayIn the 21st century, Antarctica is an icy landscape, largely known for its harrowing survival stories of early adventurers, charming birds, and the harsh winters. It's not until Antarctica permanently separated from South America, forming the circum-Antarctic current, that it reached the glaciated state that persisted to today (e.g., Kennett, 1977). But for much of geologic time, Antarctica was in fact much more habitable, at least for some parts of the year, with extensive forests and a much more diverse set of tetrapods. And that includes temnospondyls!

The cold snap this weekend (driven by Winter Storm Harvey and the polar vortex), inspired me (sitting in my house without functional internet but with functional heat) to write this week’s blog post about temnospondyls from the South Pole. Harvey originated from a low-pressure system off the coast of the Pacific Northwest, which is particularly apropos for this week’s blog because much of the recent work on Antarctic temnospondyls has been done by paleontologist Chris Sidor at the University of Washington / Burke Museum over in Seattle. If you look at a temnospondyl skull, it is decidedly not smooth like our own. Instead, it may be covered by any (or all) of the following: pits, grooves, ridges, tubercles, or nodules. Don't confuse this for pebbly or bumpy skin texture like in some modern reptiles that are formed by separate scales or osteoderms that sit on the skull (or other parts of the body) - these bumps develop as part of the skull! This week's blog post is covering dermal ornamentation, naturally with a focus on temnospondyls. A lot of this week's blog is derived / inspired by work by Florian Witzmann at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin who has done lots of very cool work on temnospondyls in general but also with respect to their bones. |

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed