|

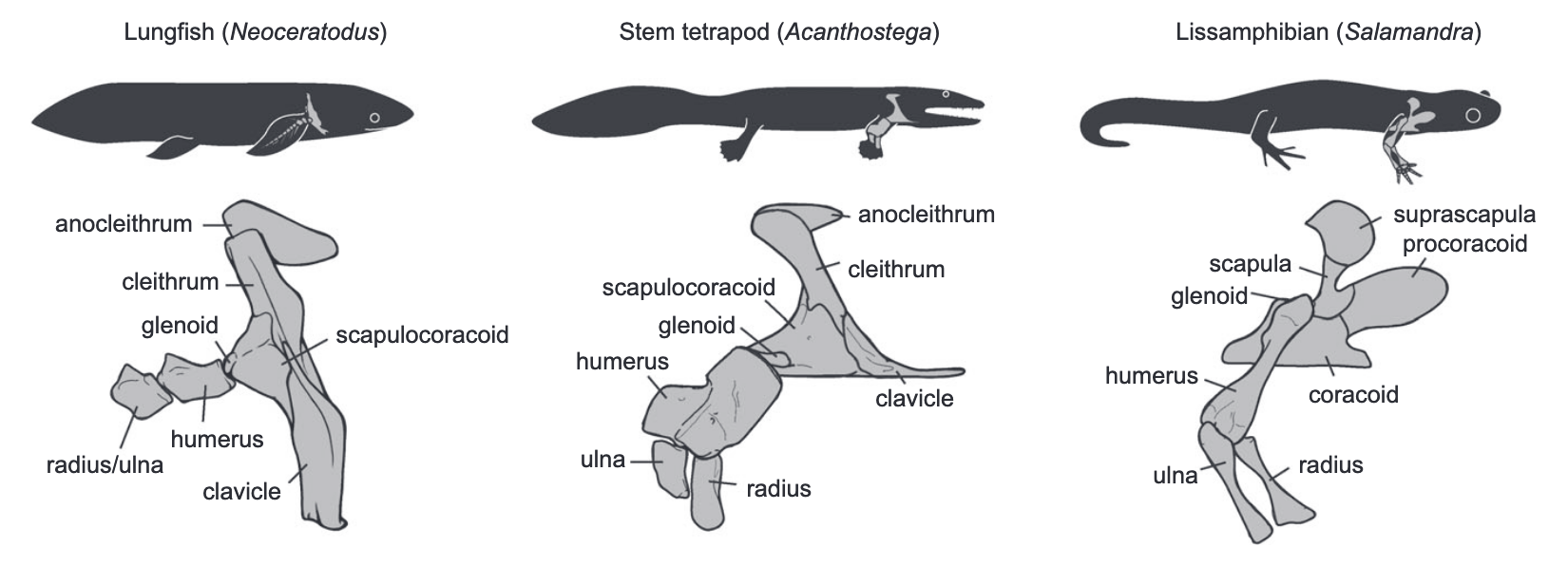

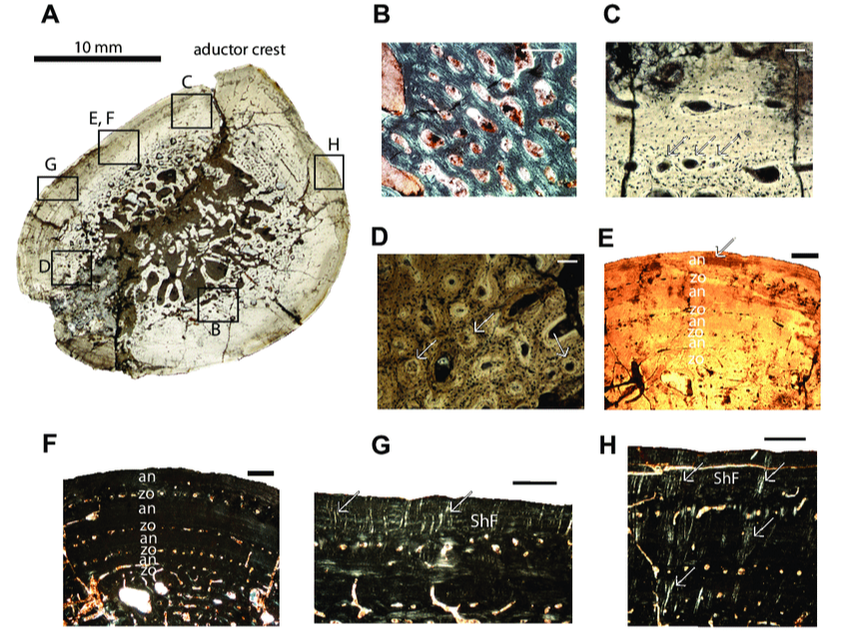

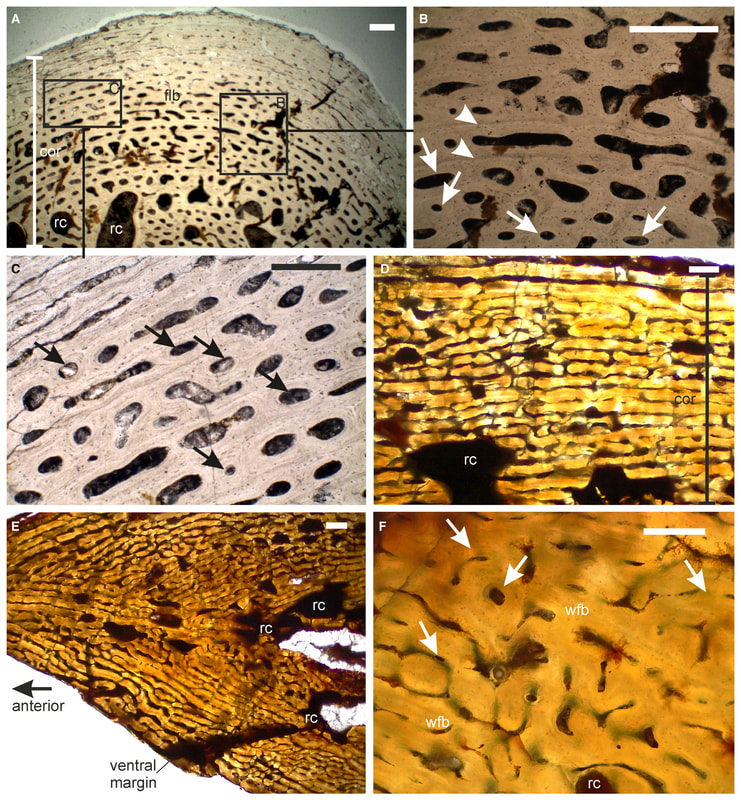

The limb gets a lot of attention because it's the part of the body in direct contact with the ground (or in the case of some animals, avoiding contact with the ground). But equally important is the apparatus that connects to the limbs - the girdles! What we call the shoulder girdle is scientifically termed the 'pectoral girdle,' while what we call the hip or the pelvis is termed the 'pelvic girdle.' This week's post will look at the pectoral girdle! Temnospondyls have four to five different elements in their pectoral girdle: the interclavicle, the clavicle, the cleithrum, and the scapula + the coracoid / a composite scapulocoracoid. Stem tetrapods (like Acanthostega in the middle below) have an anocleithrum inherited from our fishy forerunners, but this is absent in all temnospondyls. Conversely, some extra bones are found in modern amphibians (like Salamandra on the right below). Several of these will sound unfamiliar to people who only know mammals because we (and other mammals) lack cleithra and interclavicles. Last week, I covered the external anatomy of limbs, which is often one key datapoint used to infer the lifestyle of temnospondyls - after all, limbs change quite a lot depending on whether you need to walk around on land or merely paddle in the water. But external anatomy isn't the only useful thing about a fossilized limb. Thin-sectioning, or the process of slicing a fossil or bone and making a thin section out of it for examination under a microscope allows us to examine microscopic structures that offer insights into how that bone grew. This in turn can be extrapolated to how the entire animal grew and is a powerful source of data for testing hypotheses about lifestyle and ecology more broadly. In today's post, I'll be covering histology and microanatomy, the two main attributes of the internal bone that we can derive from fossils. Last week, I covered what the skull might tell us about an animal's ecology. The skull contains a lot of important sensory organs and is a major part of several major functions, like feeding and breathing, not to mention that skulls are very diagnostic in the fossil record compared to other elements. However, one important function that the skull typically does not fulfill is locomotion (the exception is animals that use their head to burrow into dirt or sand). Because locomotion is such a critical function, tetrapods have modified their limbs in a remarkable variety of ways to adapt to their local environment. Fundamentally, the same bones are present in the limbs of all tetrapods, but different ones have taken on drastically different shapes to best serve their function. For example, the limbs of swimming mammals (particularly the arms) have shortened drastically, while the fingers have become elongated, forming the distinctive paddle.

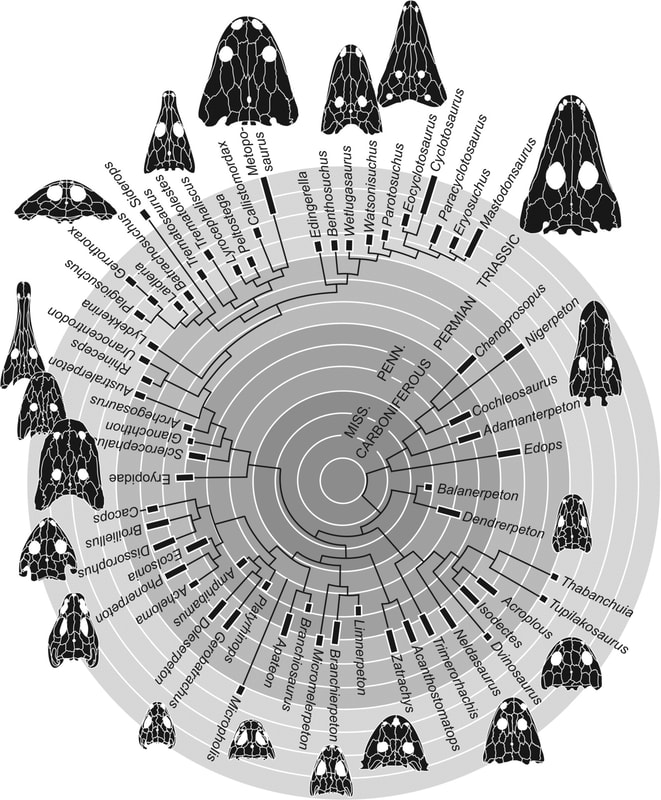

To kick off this topical series looking at how we know what we claim to know about temnospondyls, we'll start with the most recognizable part of any animal: the head! Lots of important things happen up at the head - breathing, eating, and plenty of sensory functions from smell to hearing. So it stands to reason that the skull might offer us a good deal of insight into the lifestyle and ecology of temnospondyls. Shapes and sizes

Overview New (school) year, new blog series! Now that society is crawling back towards some semblance of "normal," I'm making a valiant effort to get back to more regular blogging, and to try to keep myself accountable, I'm starting a topical series that I'm calling "How do we know...?" (for now anyway). In this first part of the series, I want to focus mostly on one of the most interesting yet cryptic (and thus often controversial) parts of temnospondyl paleobiology: their lifestyles! We'll start with the basics - how do we know what kind of environments temnospondyls lived in - and go from there. I'm also hoping to feature a lot of cool temnospondyl paleoart because there's more and more of it coming out! All of the above art is by Gabriel Ugueto (website here; Twitter here), who has done a ton of art for a book that hopefully will come out soon ("Journey to the Mesozoic").

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed