Temnospondyls are undoubtedly some wonky animals in general, as they look like a cross between a salamander and a crocodile and do all sorts of weird and wonderful things. Ned Colbert once referred to stereospondyls as "queerly proportioned beasts such as we might encounter in some mediaeval manuscripts," which is an excellent tagline for a LinkedIn page. Zatracheidids, though not stereospondyls, are "queerly proportioned" so to speak and have also inspired some really great quotes, perhaps not quite at the typical level of proper academic writing, that live in perpetuity in the literature. Below are some of my favourites:

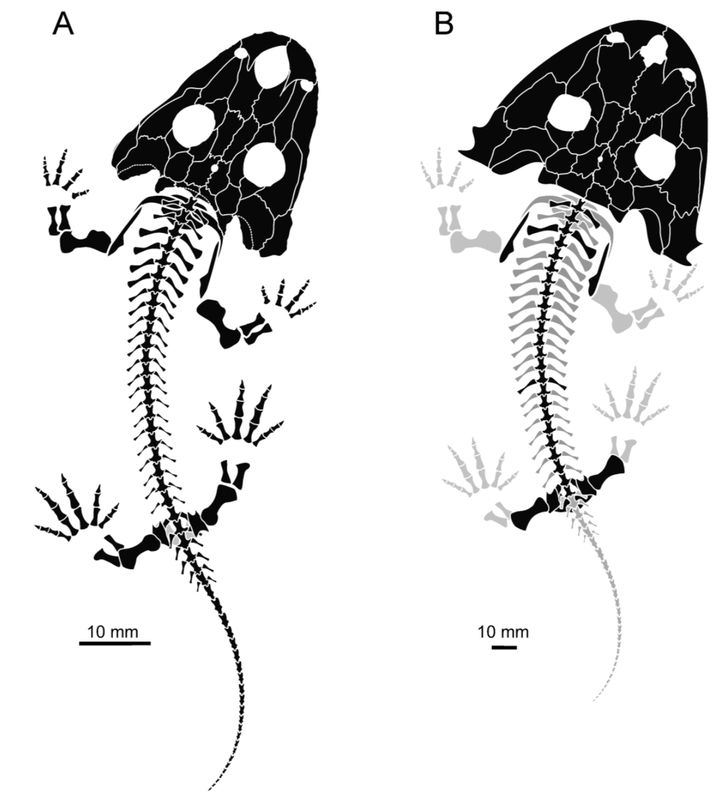

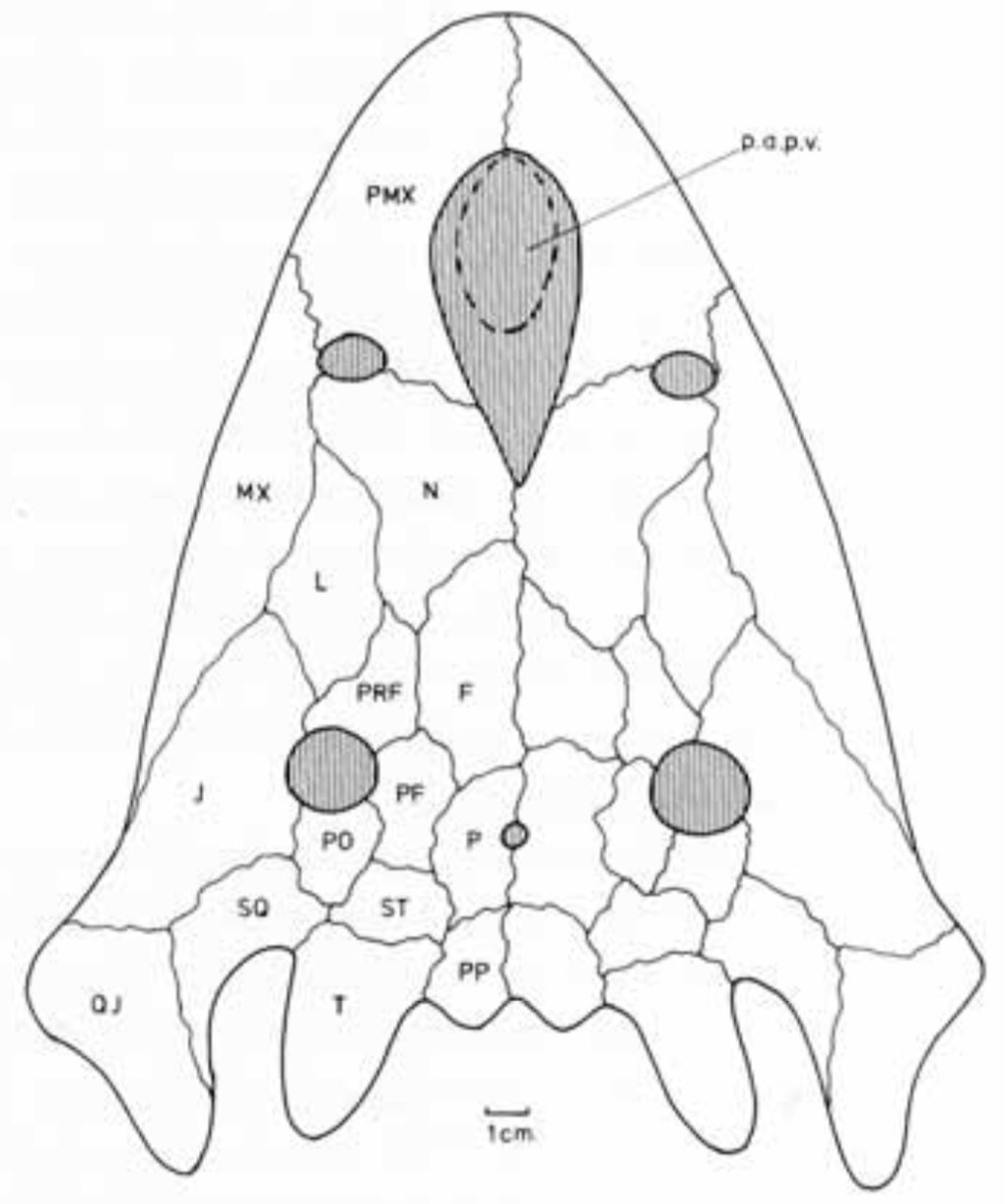

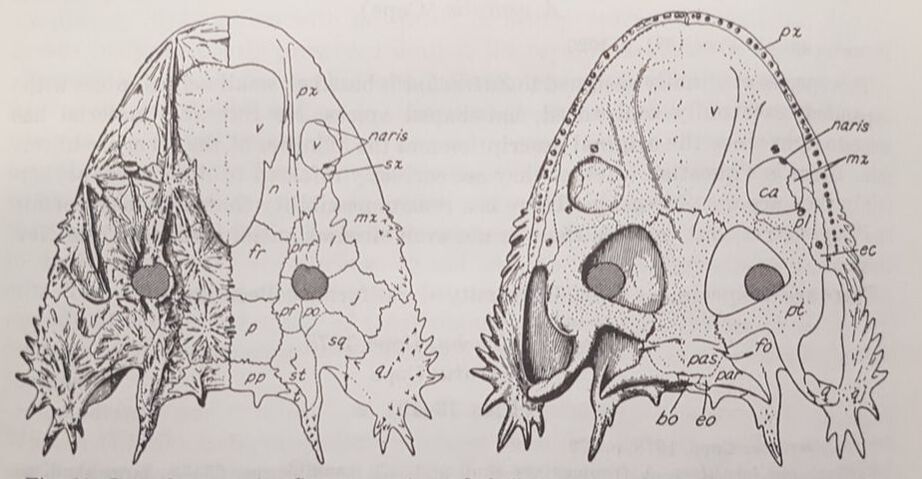

AcanthostomatopsAcanthostomatops is the first of two zatracheidids from Europe, being known from several dozen specimens collected from an early Permian locality near Dresden, Germany. Of the zatracheidids, it is the smallest, has the proportionately widest skull and smallest internarial fontanelle, and the best-known ontogenetic series (see below), described both by Boy (1989) and Witzmann & Schoch (2006). A larval specimen reported by Werneburg (1998) has been re-identified as a micromelerpetid by Witzmann & Schoch (2006). The genus was originally named Acanthostoma, with detailed descriptions being made by Credner (1883) and Steen & Brough (1937), but this name was already taken by some esoteric polychaete worm that got the name 70 years before the temnospondyl, so it changed in 1961 by German paleontologist Oskar Kuhn. Among the detailed ontogenetic information available through the large sample size is an apparent change in the hyobranchial apparatus from larval forms to adults. Witzmann & Schoch (2006) suggested that this might relate to the development of a complex tongue apparatus that would have been adaptive in terrestrial environments, possibly as an ambush predator. DasycepsDasyceps is one of the few Paleozoic temnospondyls from the U.K. It was originally described as a species of the genus "Labyrinthodon" (no longer valid, now a junior synonym of Mastodonsaurus) but was subsequently recognized as a distinct species by Thomas Huxley in 1859 and given its present name. It was redescribed (in German) by von Huene in 1910, and following the description of the other zatracheidids, also identified as such early in the 20th century by Case. At one point, it was regarded as synonymous with Zatrachys (Broom, 1913), but this opinion never really took off, and the possible juvenile-adult relationship between Acanthostomatops and Zatrachys has garnered more attention in recent history. Dasyceps is the largest known zatracheidid, with a skull length approaching 30 cm, and the skull is proportionately long compared to the shorter and more parabolic skulls of Acanthostomatops and Zatrachys. Its internarial fontanelle is a perfect teardrop and is preserved as such in the holotype - it's not a reconstruction that is artificially smoothed to look nice. Other features in which it differs from other zatracheidids include a narrower otic notch, relatively smaller orbits and nares, and broad, posteriorly extensive tabular horns (slender in Zatrachys). It also lacks the spiky projections from the lower cheek region that are found in other taxa, although it still has markedly expanded quadratojugals. Whether some of these features are associated with size (and possibly advanced ontogenetic maturity) is unclear. The first species of Dasyceps is Dasyceps bucklandi, named after the famous 19th century paleontologist William Buckland. A second species from the early Permian of Texas, Dasyceps microphthalmus, was originally described in 1896 by Cope as a species of Zatrachys; it was subsequently moved over by Paton (1975). This species is much more poorly known than D. bucklandi, being represented only by a poorly preserved holotype "covered in bean ore" (Cope, 1896), whatever 'bean ore' is, and two fragmentary referred skulls. If the generic assignment is correct (I have no reason to question it), this would be one of the most geographically wide-ranging genera of Paleozoic temnospondyls (ignoring the present-day separation of the U.K. and Texas); most taxa, particularly terrestrial ones, are fairly restricted. Milner et al. (2007) identified a small zatracheidid from the early Permian of the Czech Republic that they referred to Dasyceps sp. ZatrachysZatrachys is one of the more iconic North American Permian temnospondyls if only because zatracheidids generally look weird. The first species, Z. serratus, was named in 1878 by E.D. Cope for material collected from Texas, but the material was relatively fragmentary, which led to reconstructions that more closely resembled Dasyceps. Additional, seemingly by random chance, the holotypes of Z. serratus and 'Z. microphthlamus' (now in Dasyceps) are lost, as is that of 'Zatrachys conchigerus,' which is now a nomen vanum. None was ever very clearly illustrated either. The neotype of Z. serratus is just the back half of a skull, which is badly weathered, thus preserving little of the cheek spines and none of the internarial fontanelle. The best-known material is thus that described from New Mexico by Langston (1953) and Schoch (1997), which includes complete skulls of several growth stages and which captures a range of intraspecific variation. A number of other species have been named under Zatrachys, but most of these are now regarded either as indeterminate temnospondyls or more specifically as some kind of aspidosaurine dissorophid, and it has also been confused with the dissorophid Platyhystrix on account of erroneous association of skeletal remains. Among them are Zatrachys apicalis and Zatrachys crucifer, which are both placed in Aspidosaurus now.  Photo of the Pinocchio Frog; © Tim Laman/National Geographic Photo of the Pinocchio Frog; © Tim Laman/National Geographic So what's the giant hole for? The popular suggestion of the time, which is arguably still the popular suggestion of today, is that the fontanelle of temnospondyls housed a gland at least similar to, if not homologous with, the glandula intermaxillaris in modern amphibians (e.g., von Huene, 1910; Säve-Söderbergh, 1935), which is what produces the sticky secretion that then gets adhered to the tongue for snagging insects. This does explain why many terrestrial temnospondyls have a fontanelle, with a corresponding intervomerine depression just below it on the roof of the mouth, but it fails to account for the massively enlarged fontanelle of zatracheidids - what would compel an animal to need so much of that secretion compared to other animals of a presumed similar ecology? It's not even clear, as noted in the above quote by Paton (1975), whether Dasyceps could sustain itself on insects given its size (though sticky secretions can probably help snag small tetrapods too). If the gland was indeed much larger and produced a much larger volume of secretion, then it would probably have to be a very situational thing, perhaps akin to how hagfish exude thick coats of mucus to clog a predator's mouth, otherwise the amount of water required to produce that much mucus would be prohibitively costly for the animal. So the TLDR is that it doesn't seem very likely that the gland would be orders of magnitude larger than in any other temnospondyl. The better, although hardly substantiable, suggestion is that of Paton (1975), who provided a detailed re-description of Dasyceps from England. She suggested that the fontanelle in zatracheidids housed an expandable sac that would inflate as a defence mechanism. There is admittedly no real justification for this, but it does vaguely remind me of the Pinocchio Frog (discovered in 2008, described in 2019), which can inflate that little trunk it's got sticking off its face. What about the spikes? Other than Langston's (1953) suggestion that the spikes made Zatrachys less palatable to sharks, there isn't a clear function of the spikes, which are also absent in Dasyceps. Langston compared them to those of phrynosomatids, more commonly called 'horned toads' (but they're lizards). There is also an appreciable amount of variability in the development of the spines within Zatrachys; they may have only been ornamental structures. The presence of spikes in the Carboniferous-age Stegops has long been cited as evidence for affinities of that taxon with zatracheidids, but it more commonly comes out as an early dissorophoid. Updated Wikipedia articles! I don't publicize this much, but I go through from time to time, usually when I'm procrastinating my dissertation, and touch up (i.e. massively expand) the articles for early tetrapods that I have some familiarity with (I actually don't do metoposaurids much because of a concern, probably unfounded, that I'm too close to the subject matter to be unbiased in how I present certain information). Most of the "lower tetrapods" only have a single sentence, so there's a lot of work to be done. That was the case for all of the zatracheidids, so I've updated those pages along the lines of the content I wrote above: Refs

David Marjanović

1/15/2020 12:58:10 pm

"Updated Wikipedia articles!" Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed