|

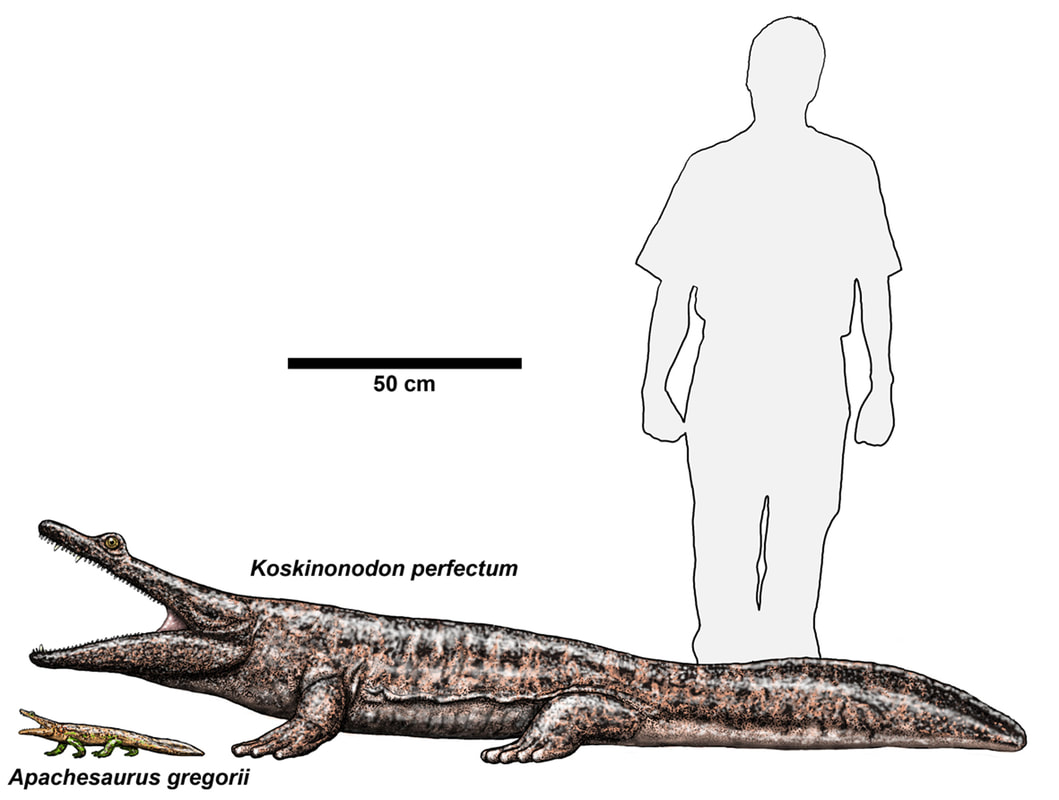

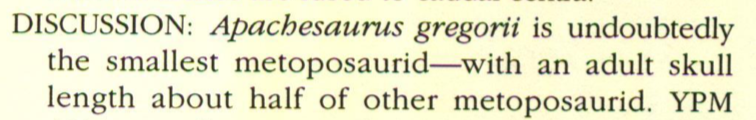

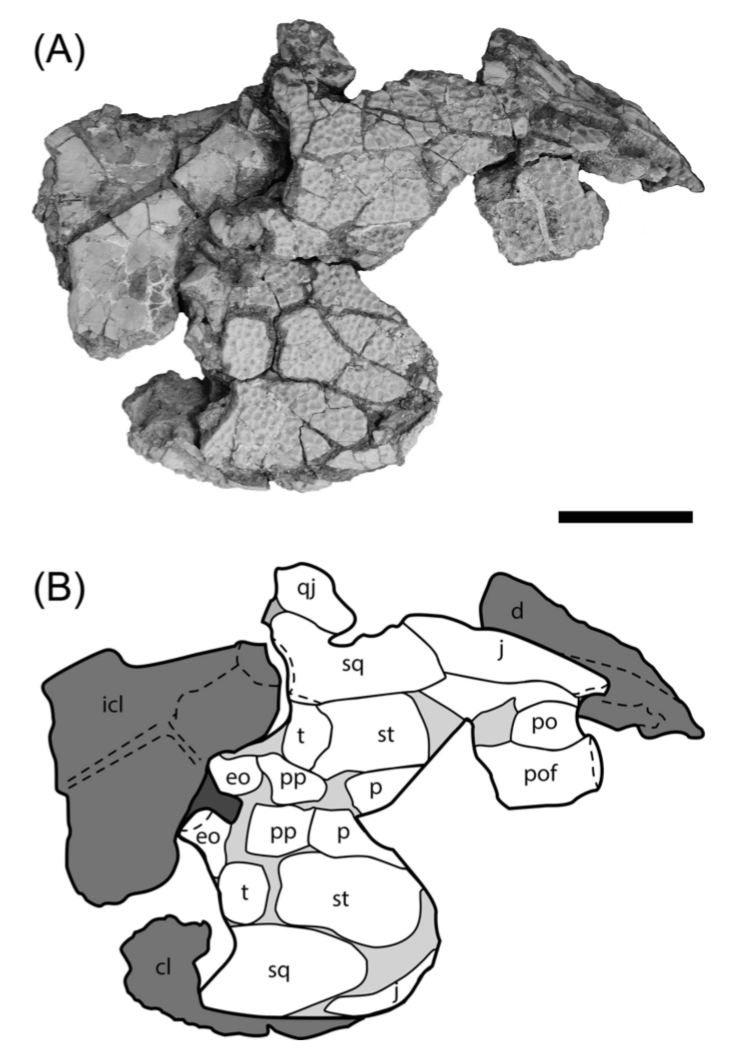

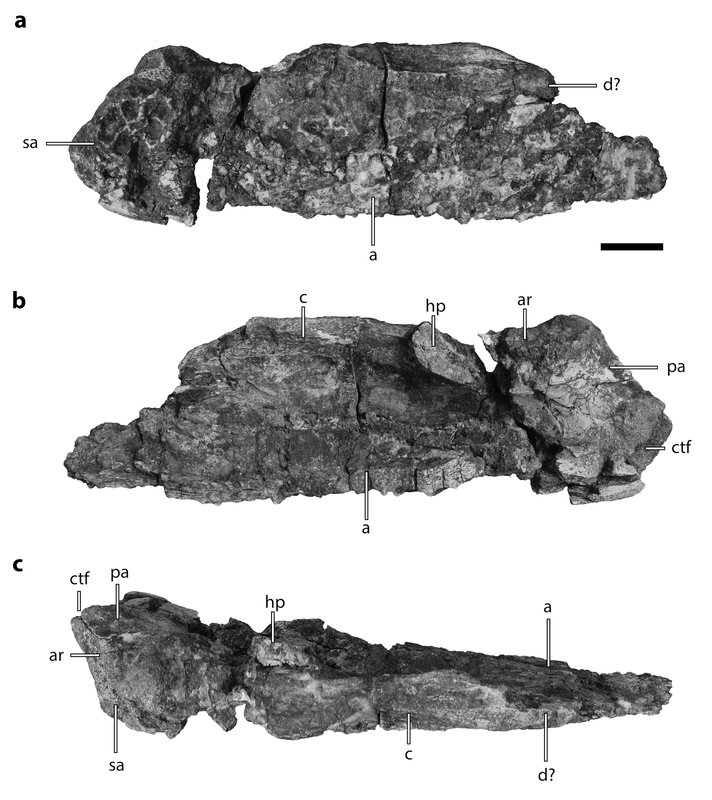

Had to skip last week because of a hectic last week of classes schedule, but I'm back this week with a blog post that's near and dear to my heart and that's been on my mind a lot between doing some collections work with Aaron Kufner (PhD student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison) a few weeks back and going out to Madison this week to give a talk on the subject matter at their student symposium. It's almost the two-year anniversary of my first paper too! For a lot of folks, you already know what I'm going to talk about, but for the uninitiated, I'll be talking about my favourite temnospondyls this week - metoposaurids - more specifically all the problems with a particular taxon, Apachesaurus. I've published several papers on this taxon and probably seem like I have a vendetta against it at this point... Because I didn't even have a website when most of these papers were published, let alone blog, this is also a great chance to read up on some of my existing publications outside of my dissertation work! Metoposaurids? Really everyone should know about metoposaurids, but for people who have been unfortunate enough to never cross paths with one, they are an extremely abundant Late Triassic freshwater temnospondyl found across much of North America and western Europe but also in northern Africa, Madagascar, and India. Their name comes from the position of their eyes, which are relatively far forward: 'metoposaurid' = 'front lizard.' They're in the medium-sized range (adults around 2 m long) for Mesozoic temnospondyls, but you still wouldn't want to run into one. They're probably one of the most common fossils in many Late Triassic deposits, but a lot of people sadly ignore them (or deliberately step on them *cough cough* archosaur workers). So Apachesaurus? As I noted above, most metoposaurids got appreciably large. The one apparent exception to this is Apachesaurus gregorii, first described from the Redonda Formation of New Mexico by Hunt (1993) (but mentioned by a number of other workers for over a decade prior). This taxon occurs relatively late in the Triassic and was apparently unique in being substantially smaller than all other metoposaurids, which led to a suggestion that in the last stages of their evolution, metoposaurids got really small in response to changing environmental conditions. I've included a literal screenshot of the page (Hunt, 1993:85) below because a certain someone told me at a conference that size diminution had never been claimed and that Apachesaurus was obviously just another regular ol' metoposaurid. The situation Hunt (1993) justified Apachesaurus as a new taxon, specifically of a small-bodied and definitely not juvenile metoposaurid, through four criteria:

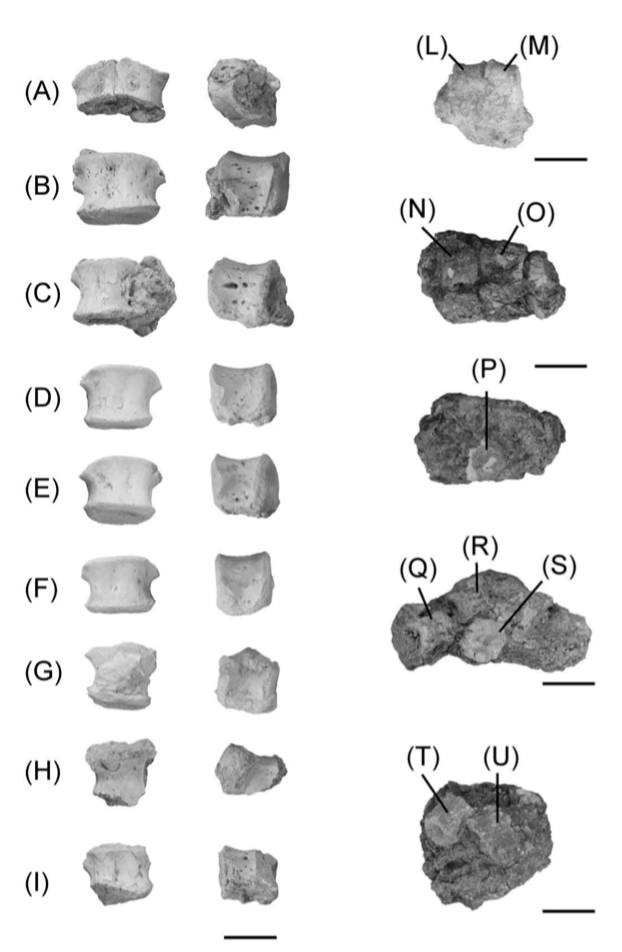

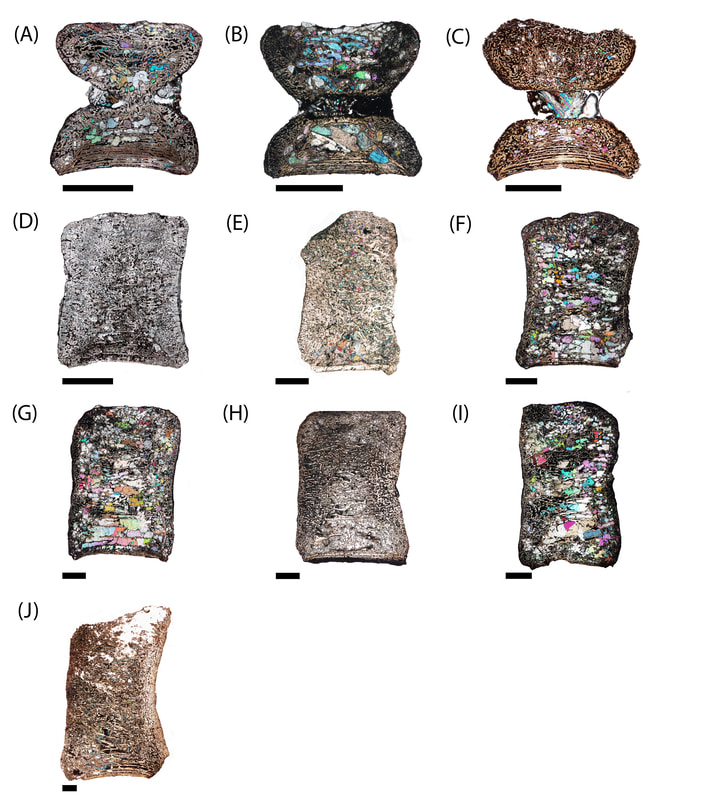

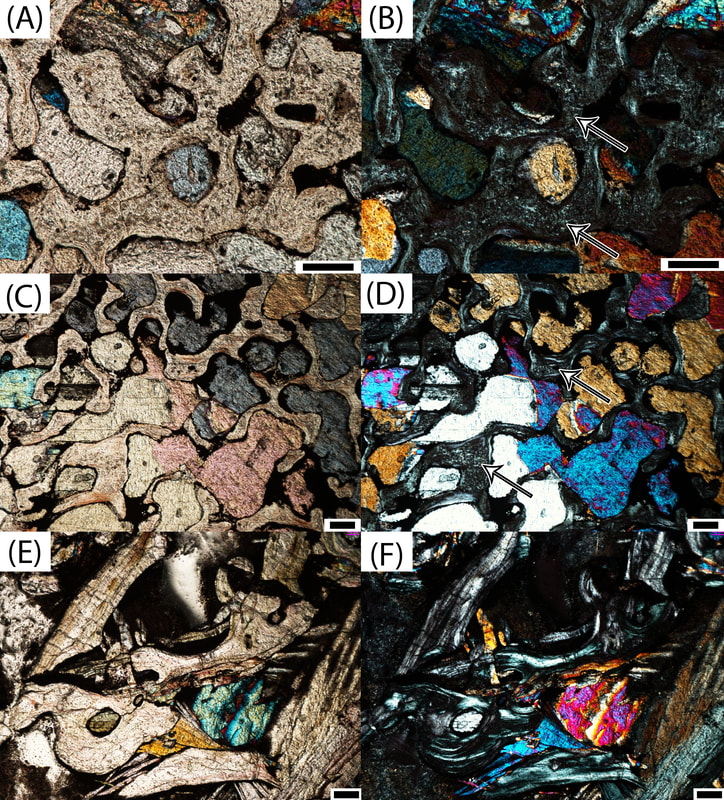

The problem(s) The above lines of evidence are not fundamentally bad justifications. But there are a lot of potential alternative interpretations that are equally likely. Considering that the sample size of metoposaurids is better than 95% of other extinct tetrapods, you'd think we actually know basically everything there is to know. FALSE. There are perhaps hundreds of skulls of large-bodied metoposaurids, including dozens that are complete. The sample size of small-bodied (either juveniles or small "adults') metoposaurids (#1) is around two dozen, and most of those are so incomplete or beat up that it can't even be determined which genus they belong to without relying on secondary support like which geographic region they occur in. This isn't unique to metoposaurids (in fact almost any extinct tetrapod is plagued by these issues), but it does mean that we still know next to nothing about metoposaurid development - which anatomical features change, when they change, how much variation there can be early in development, etc (#2, #4). Additionally, although the absence of large-bodied metoposaurids (#3) sounds compelling, it's important to remember that the fossil record is always biased. Almost never do we get even a half complete growth series of most extinct tetrapods, and major growth stages are entirely absent from the fossil record in many cases. For example, fossil amphibian larvae (i.e. tadpoles) are exceptionally rare (see Yuan et al., 2004 for an example). This doesn't mean that tadpoles didn't exist, but rather that they were not preserved for a number of reasons (e.g., no bones, not living in environments that get preserved, decay easily, etc.). As scientists like to say, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. The most important question is how do you prove that a taxon represents a diminutive form (implying a major developmental shift to substantially smaller body size)? I do want to point out that although a lot of people (including myself) use the term 'dwarfism' to refer to this purported phenomenon in Apachesaurus, you need a phylogeny to show that it's a trend from large -> small and not from small -> large (which gets all kind of complicated because dwarf taxa can screw up your phylogeny, and there is no good one for metoposaurids anyway...). So I'm just referring to it as size diminution here, as I did with my last paper on the matter (Gee & Parker, 2018b). Morphological observations may clue you in, but ultimately you can only make relative assessments of an animal's age and maturity from its skeleton alone. You can't look at someone's skeleton and know that they were born on August 23, 1978. This is naturally even more poignant for extinct tetrapods for which we know next to nothing about growth patterns. I've gone three different routes to try to better tackle this problem using specimens from Petrified Forest National Park (PEFO) in Arizona:

Primary conclusions

So how do we explain the patterns that we see and reconcile them with previous interpretations?

TLDR: There is no evidence that Apachesaurus is a small-bodied adult. P.S. I want to go on record as saying that I did not change the Wikipedia page for Apachesaurus, which now redirects to Koskinonodon (the large-bodied metoposaurid that co-occurs with Apachesaurus). I think it's funny, but don't believe everything you see on the internet. This misconception probably comes from my first paper in PeerJ where I suggested that Apachesaurus might be a juvenile of an existing metoposaurid taxon, the most likely candidate of which is Koskinonodon. I didn't formally synonymize anything though, didn't reiterate that specific claim in more recent papers, and don't currently think that that's true, and suffice to say, it's essentially someone overextrapolating from my work; frankly I have no idea who edits a lot of these Wikipedia pages... Refs

David Marjanović

4/28/2019 03:38:01 pm

"'metoposaurid' = 'front lizard.'" Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed