New publication: CT data on the 'microsaur' Llistrofus (Gee, Bevitt, Garbe, & Reisz, 2019; PeerJ)1/25/2019

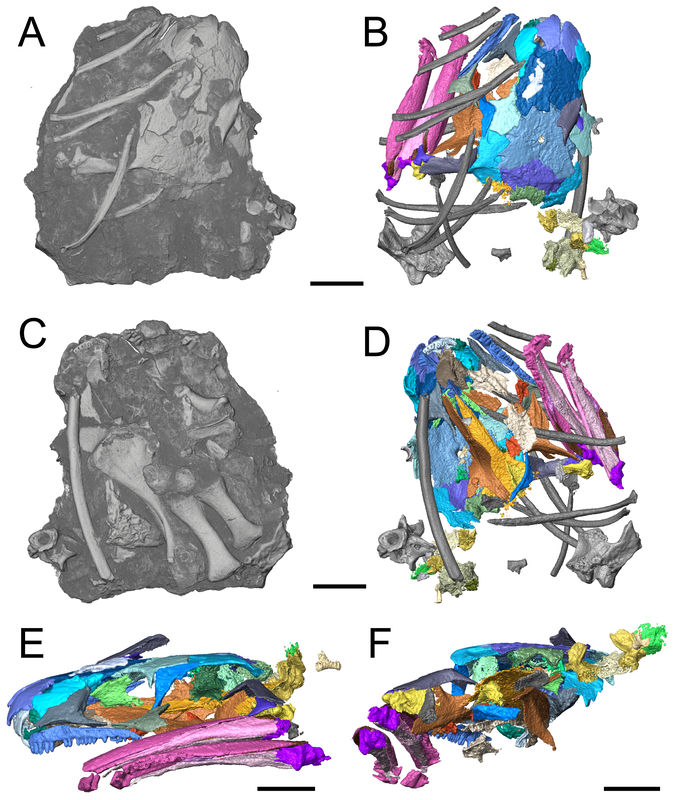

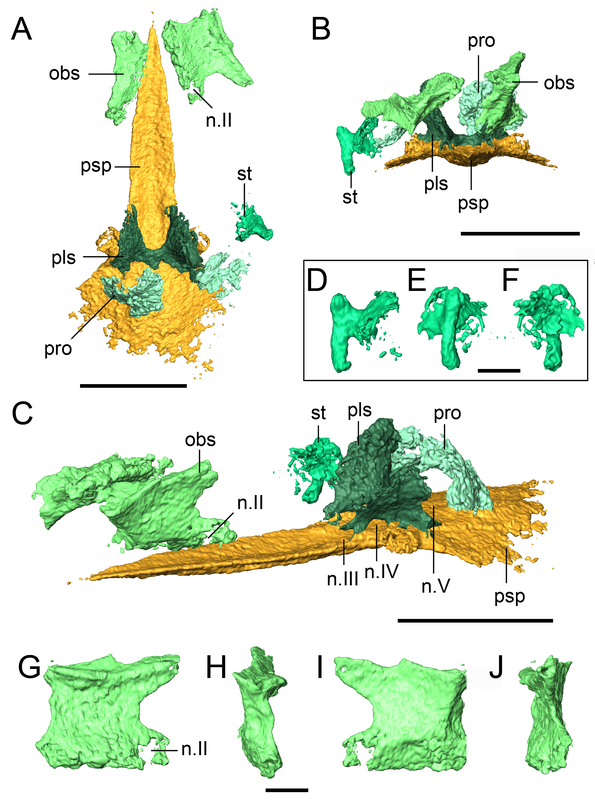

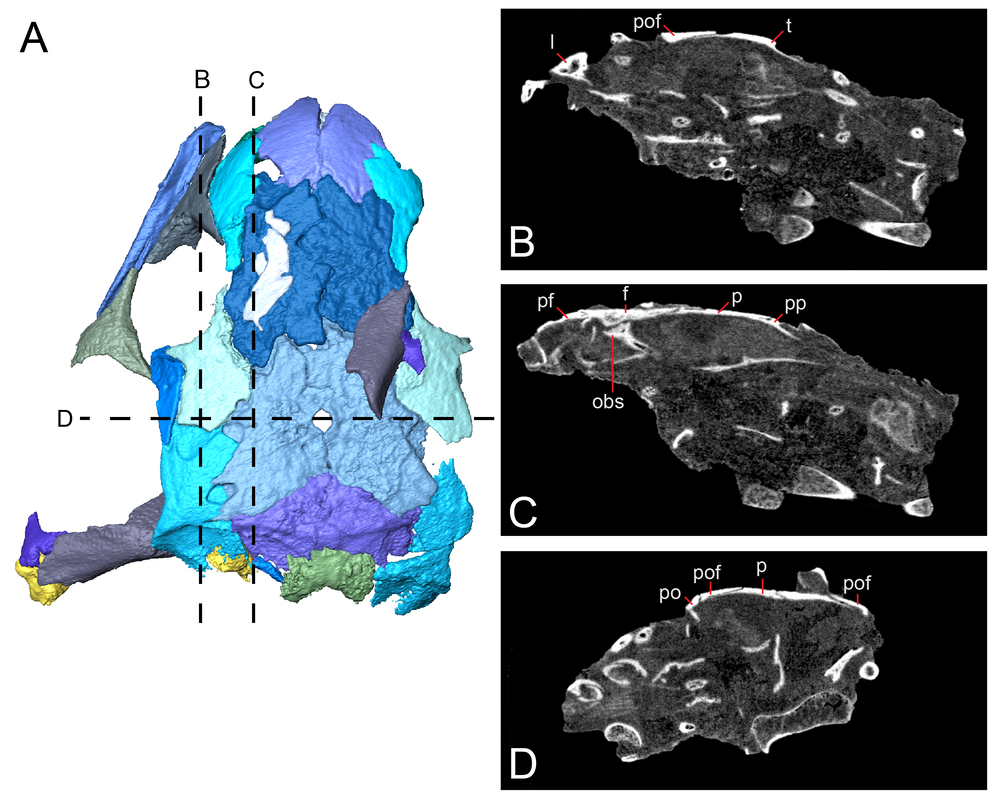

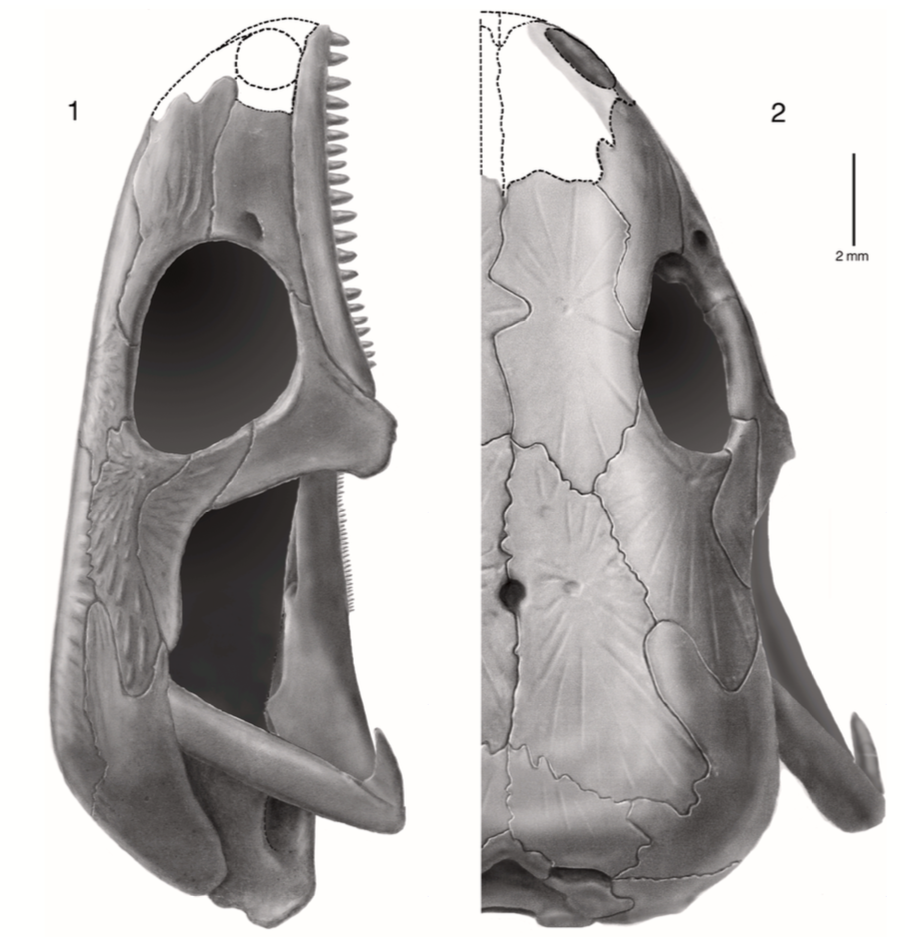

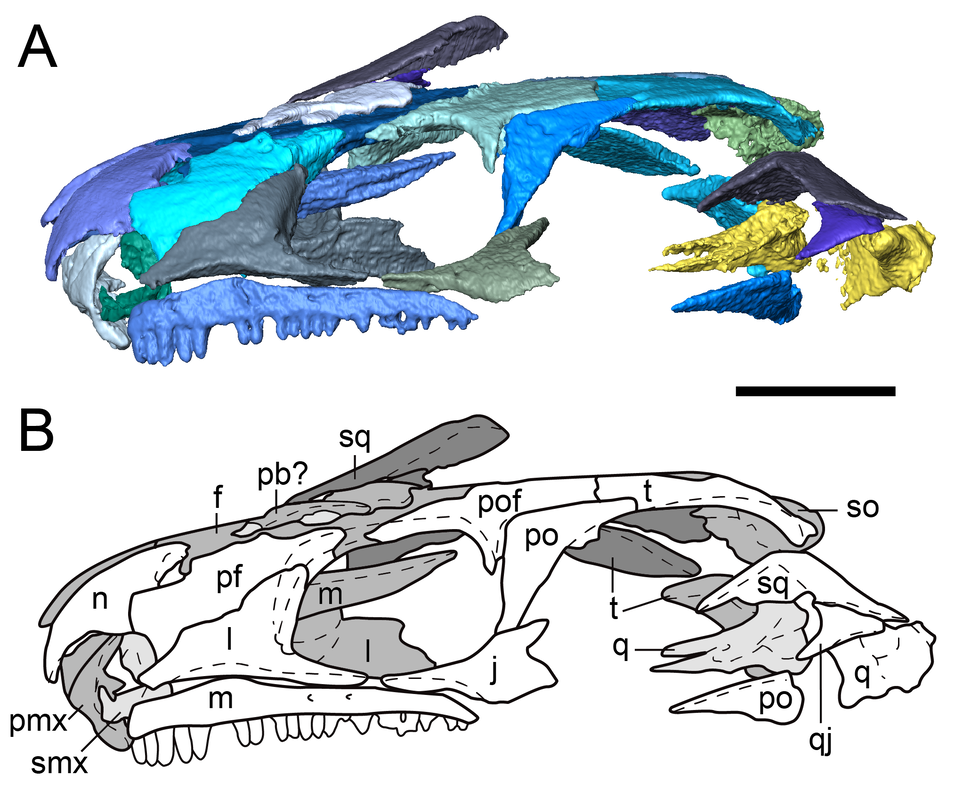

Title: New material of the ‘microsaur’ Llistrofus from the cave deposits of Richards Spur, Oklahoma and the paleoecology of the Hapsidopareiidae. Authors: B.M. Gee, J.J. Bevitt, U. Garbe, R.R. Reisz Journal: PeerJ, vol. 7, article #6327 Link to paper - this is an open access paper that can be viewed by anyone! Abstract (from paper) The Hapsidopareiidae is a group of “microsaurs” characterized by a substantial reduction of several elements in the cheek region that results in a prominent, enlarged temporal emargination. The clade comprises two markedly similar taxa from the early Permian of Oklahoma, Hapsidopareion lepton and Llistrofus pricei, which have been suggested to be synonymous by past workers. Llistrofus was previously known solely from the holotype found near Richards Spur, which consists of a dorsoventrally compressed skull in which the internal structures are difficult to characterize. Here, we present data from two new specimens of Llistrofus. This includes data collected through the use of neutron tomography, which revealed important new details of the palate and the neurocranium. Important questions within “Microsauria” related to the evolutionary transformations that likely occurred as part of the acquisition of the highly modified recumbirostran morphology for a fossorial ecology justify detailed reexamination of less well-studied taxa, such as Llistrofus. Although this study eliminates all but one of the previous features that differentiated Llistrofus and Hapsidopareion, the new data and redescription identify new features that justify the maintained separation of the two hapsidopareiids. Llistrofus possesses some of the adaptations for a fossorial lifestyle that have been identified in recumbirostrans but with a lesser degree of modification (e.g., reduced neurocranial ossification, mandibular modification). Incorporating the new data for Llistrofus into an existing phylogenetic matrix maintains the Hapsidopareiidae’s (Llistrofus + Hapsidopareion) position as the sister group to Recumbirostra. Given its phylogenetic position, we contextualize Llistrofus within the broader “microsaur” framework. Specifically, we propose that Llistrofus may have been fossorial but was probably incapable of active burrowing in the fashion of recumbirostrans, which had more consolidated and reinforced skulls. Llistrofus may represent an earlier stage in the step-wise acquisition of the derived recumbirostran morphology and paleoecology, furthering our understanding of the evolutionary history of “microsaurs.” Summary for non-scientists Llistrofus is an early Permian 'microsaur' (so not a temnospondyl) from the same locality that most of my dissertation is on, Richards Spur, Oklahoma. Previously, we only had a single specimen of this taxon, so not a whole lot is known about it. This is particularly important because 'microsaurs' are fairly well-studied but lack consensus on their relationships to other tetrapod groups. A particular subset of 'microsaurs' (called recumbirostrans because they have recumbent snouts) evolved to be specialized burrowers, and their braincases reflect this in being much more ossified (more hard, bony parts) than a lot of contemporaneous tetrapods (including most temnospondyls). However, we don't know as much about the early evolution of 'microsaurs' when they were presumably less specialized. In this paper, we describe two new specimens of Llistrofus, including one that was analyzed using neutron tomography, a pretty fancy method similar to x-ray-based CT (the typical approach in medicine for example). Through this, we get a lot more data on features that are normally hard to access in fossils (e.g., the braincase). Llistrofus starts to fill in some of the gaps in early 'microsaur' evolution because it's not typically regarded as a recumbirostran (and we still don't know if it had a recumbent snout). Even if it is a recumbirostran, it's an early one within the group and doesn't have the same specialization as derived recumbirostrans. It also has this peculiar feature - a giant opening (an emargination) in its cheek region - that more or less takes up the entire side of the skull behind the eye. What's it for? Not really sure, but we throw some ideas out there too. This is the first of many papers produced through collaboration between our lab and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) and really highlights the potential of neutron tomography for these fossils. If you want to learn more about neutron tomography, you can check out the general summary I wrote for my lab website. That's a weird name - what's it mean? Llistrofus doesn't "mean" anything because it's derived from the classical name for the locality - Fort Sill - spelled backwards and with a standard -us ending to make it scientific. The species name, pricei, is for Dr. Llewellyn Price, a well-known Brazilian paleontologist. This genus and species was named in 1978 by Dr. Robert Carroll and Ms. Pamela Gaskill. What's a 'microsaur?' And why's it always in quotes? 'Microsaurs' are pretty weird tetrapods. Most of them are pretty small (the skull of Llistrofus is less than 3 cm long), and a lot of them show specializations for some sort of fossorial (living underground) or burrowing behaviours, and their phylogenetic relationships within early tetrapods remain hotly debated. Historically they've been proposed to be everything from the early ancestors of modern amphibians to crown amniotes, which sort of illustrates just how little we know sometimes about early tetrapods when paleontologists can't even agree whether these animals are closer to amphibians or reptiles. The quotation marks refer to the consensus that this grouping as historically recognized is not monophyletic. 'Monophyletic' is a phylogenetic term that refers to the composition of a group, specifically a common ancestor and all of its descendants (this link and this blog post do a good job of explaining the basics). Non-monophyletic groupings can either be paraphyletic (last common ancestor and only some descendants) or polyphyletic (some to all descendants, common ancestor excluded). People aim for monophyletic groupings because they reflect our current understanding of the evolutionary history of that group. A lot of groups that were erected decades or centuries ago are not monophyletic because (a) computational methods for phylogenetics were not a thing and (b) features thought to be shared by ancestry and thus used to group organisms may reflect convergence in different evolutionary lineages (homoplasy) rather than shared ancestry (homology). For example, not all plants with red flowers are closely related to each other. This also happens with animals (e.g., not all animals with wings [birds, butterflies, bats] are closely related to each other). 'Microsaurs' are just one of many non-monophyletic fossil groups, which we recognize by the use of the quotation marks. How do you work with CT data?

Download link to a cool animation! Major highlights?

Where's your review history??? One of the more unique aspects of PeerJ is that authors are given the opportunity to publish the review history of their article. This includes previous versions of the manuscript, reviewer comments, and the authors' responses to those comments. My previous two articles (here and here) have included the review history because I think it's useful to have that information available (for a wide variety of purposes) and to be fully transparent in the spirit of open access. I didn't include the review history of this article because it is pretty complicated. The paper was originally submitted to another journal and "major revision-ed" after review by two reviewers (let's call them A and B). A month after submitting the revisions, the journal emailed me to say that the handling editor had not accessed the revised files, and that the journal was looking for a new handling editor. One month passed, during which they were unable to procure another editor, so I pulled the paper and submitted it to PeerJ, where I included this information and asked them to attempt to procure the same reviewers (A & B). After initial review in PeerJ by two reviewers (only one of them the same from the previous submission, so now we're at A & C), the paper was rejected but encouraged to be resubmitted. We made the revisions and resubmitted it again. After "initial review" by two reviewers (only one of them the same from the first PeerJ submission and not the same one from the very first submission, so now we're at C & D), it was "minor revision-ed" and then accepted after we submitted said revisions. The review history for this particular submission would thus reflect only the third of three rounds of revision of a manuscript that was examined by 4 reviewers and 2 editors in its entirety. The third version, understandably, was the most polished version, and the reviewer comments on it are very minor. It was not possible to attach the review history from the first PeerJ submission (rejected) to the second PeerJ submission (accepted), so I felt that it would be misleading to have this as the only record of review history for this paper - anyone looking at it would think that we had produced a nearly perfect paper when in fact it's undergone substantial changes in each iteration. I do want to give a big shout-out to Dr. Jen Olori (at SUNY Oswego; @Paleoswego), who gave us some of the most thorough and constructive reviews I've ever gotten! Refs

Interested in more CT studies on 'microsaurs' and friends? Check out the following papers:

David Marjanović

2/4/2019 01:06:38 pm

I've read the whole paper. It will be very useful! Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed