|

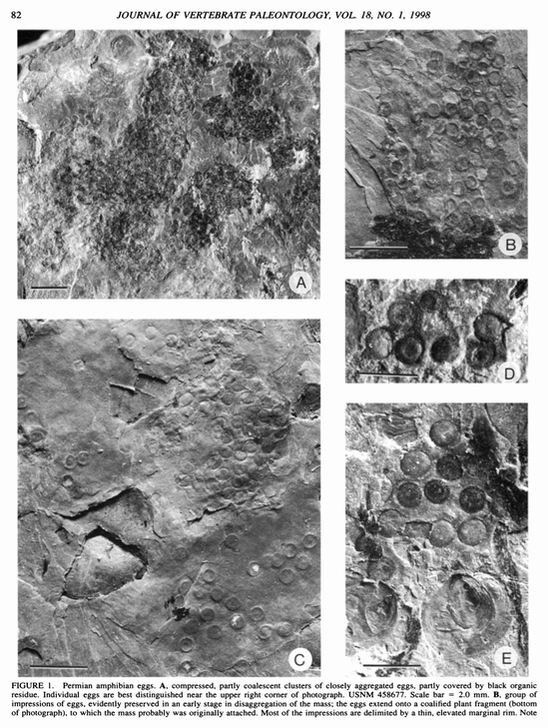

With Easter just behind us, eggs (usually the chocolate variety) are surely on most people's minds. So are things that hatch out of eggs, such as chickens. Eggs are a pretty fascinating biological structure if you think about it long enough - they're basically a mini life support system. Eggs have a long fossil record as well; they're known from many dinosaurs for example, as well as other animals that lay hard-shelled eggs. But what about temnospondyl eggs? Well unfortunately, temnospondyl eggs were almost certainly like the eggs of other "lower vertebrates" (fish + amphibians), which today, fall into the category of "soft tissues," which is to say that they don't have any mineralized components like in bones, teeth, or eggshells. Instead, they look more or less like gelatinous blobs with the developing embryo inside. Because most fossilization occurs through permineralization where the original minerals formed by the animal while it was alive are replaced by other minerals that follow the original structure, the absence of mineralized tissues in structures such as hair, feathers, skin, and in this case, some eggs, makes them unlikely to preserve. Of course, it's important to note that the absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence. For example, shelled eggs probably appear far earlier than is apparent from the fossil record, so although eggs of early amniotes are unknown, that doesn't automatically imply that they had soft, unshelled eggs (also, many reptiles have rather leathery and not-quite-hard eggshells). The most accurate way to say it is that we simply don't know much of anything about temnospondyl reproduction. BUT, we do have evidence of a single occurrence of putative temnospondyl eggs (to get back to the original question).

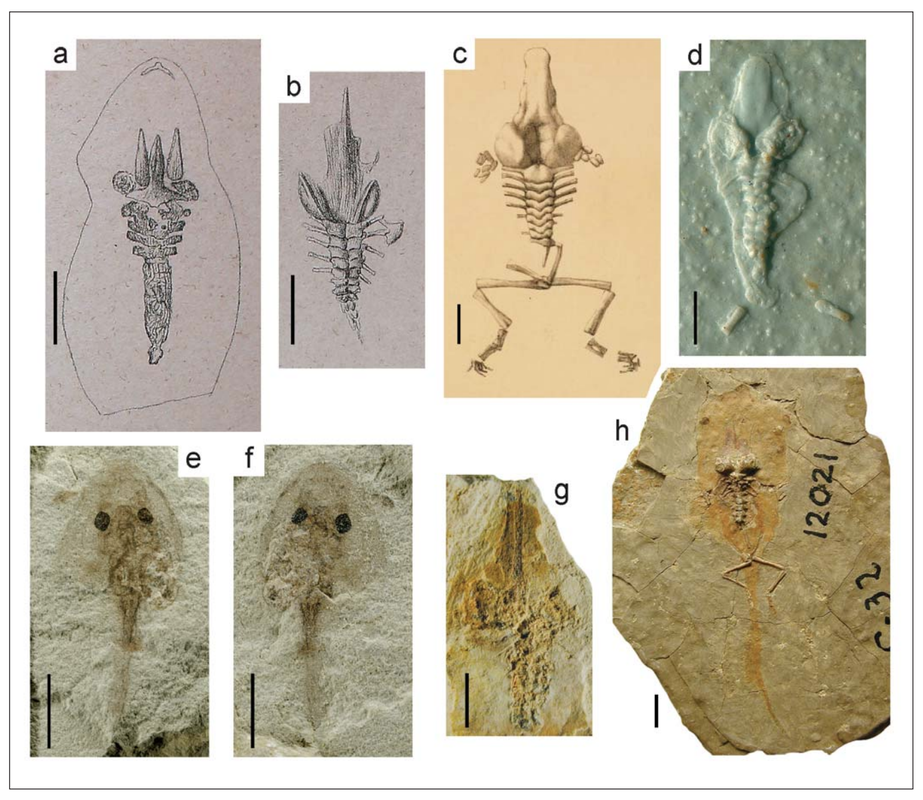

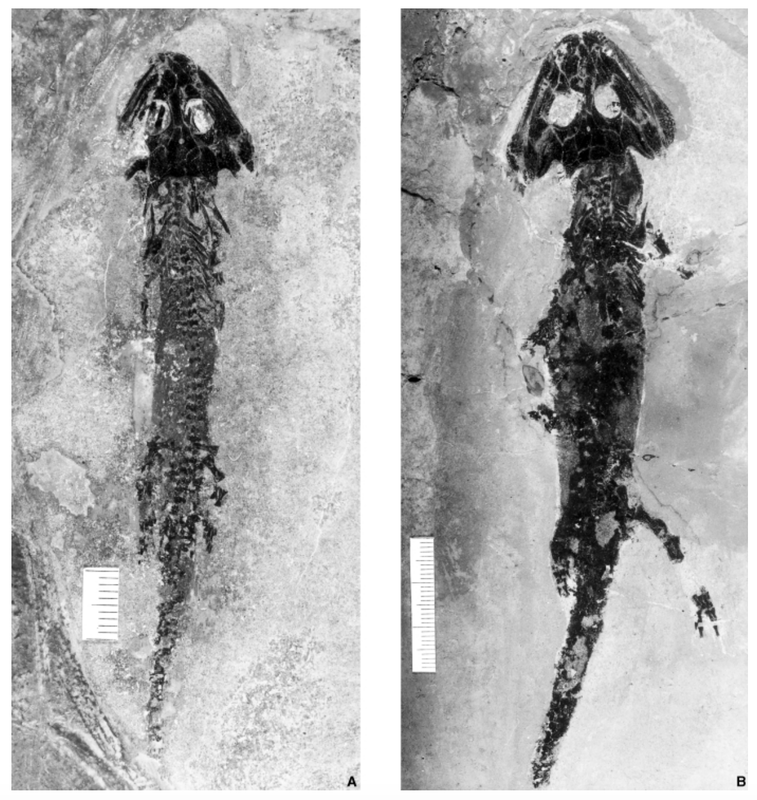

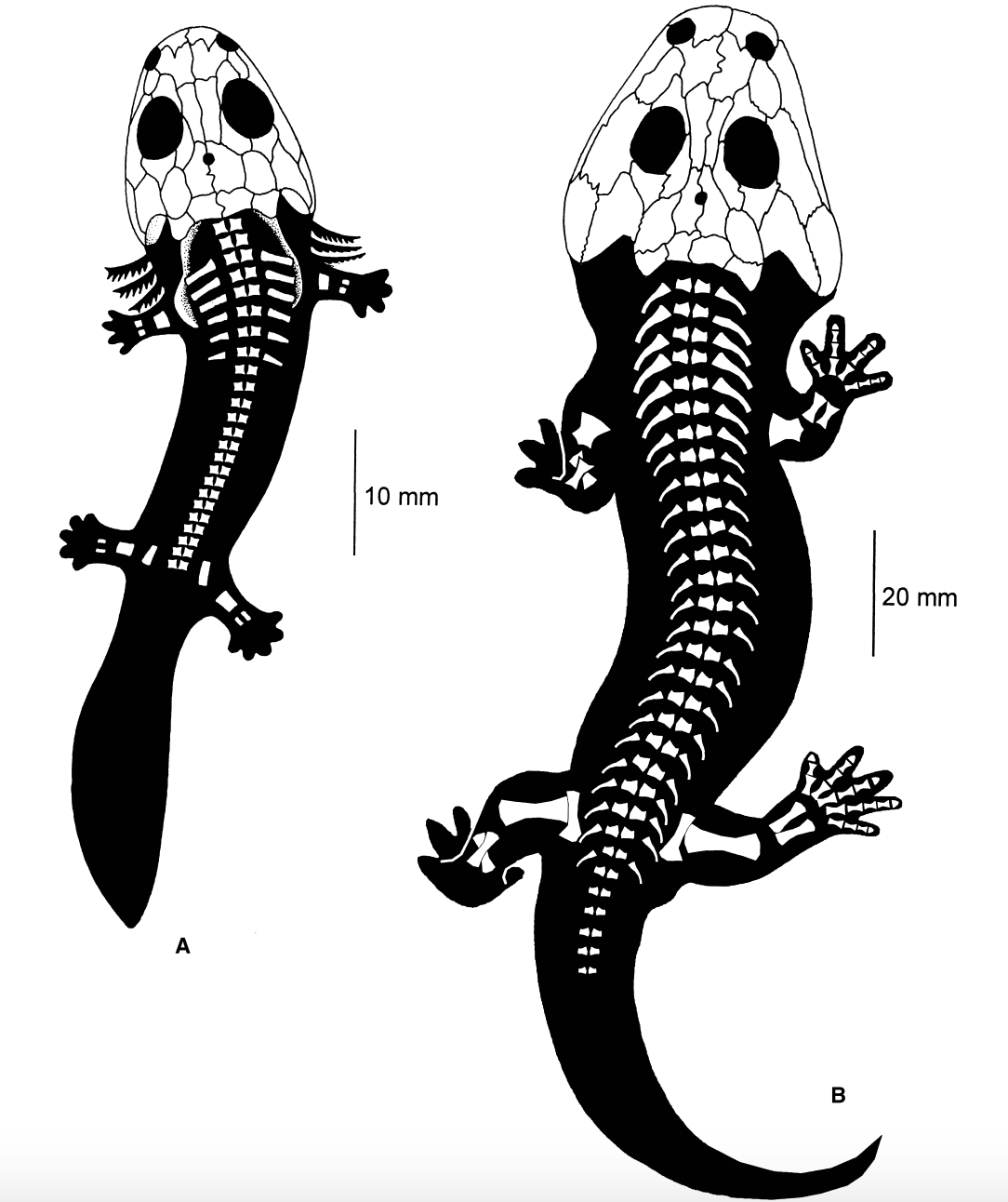

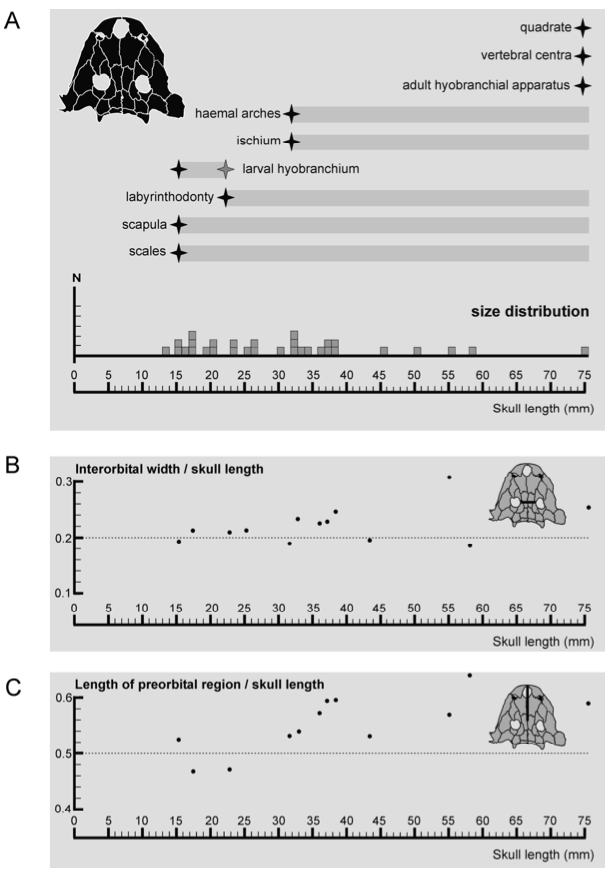

These authors presented various lines of evidence to claim that they could both identify all of the typical features of anuran (frog + toad) eggs and rule out everything other than temnospondyls, from invertebrates to other tetrapods, as the probable maker of these putative eggs. They then went on to get even more specific, suggesting that it was most likely to be dissorophoids, long thought to be of some relationship to anurans and commonly found in the early Permian of Texas. Now I am not an expert on amphibian eggs or on trace fossil interpretation. The environment is right for this type of remarkable preservation, and it's not too often that you get a bunch of perfectly circular impressions en masse in a freshwater deposit. They do look compellingly like organic structures, although I spent enough time doing geology to see a lot of structures that look biological in origin and in fact are not. Nobody has really made much of anything about these early Permian eggs (the paper only has 3 citations), but it would be interesting to revisit some of these late Paleozoic ichnofossils in light of advancements made in terms of taphonomy, community assemblages, etc. of tetrapods. There are, for example, some interesting "eggs" reported from the Carboniferous Mazon Creek locality in Illinois by Godfrey (1995). A related question I sometimes get and that I figured I would also discuss here is whether we have any record of temnospondyl tadpoles. The answer is really defined by what you consider to be a "tadpole." Tadpoles are the larval (=juvenile, pre-metamorphic) life stage in amphibian development. With a few exceptions, virtually all living species' tadpoles share an aquatic lifestyle that is accompanied by a lack of limbs, small mouths for feeding on plant matter, gills, and a number of other features that are then subsequently transformed during metamorphosis. If the question is whether we have any tadpoles that look like modern tadpoles, the answer is no. There is no evidence for anything with a round body, developed tail, mostly cartilaginous skeleton, or spirally arranged intestine that we ascribe to temnospondyls. The record of modern amphibian tadpoles in the fossil record is also quite poor; Gardner (2016) provides an updated discussion in which he indicates that there is no unequivocal tadpole fossil prior to the Cretaceous. However, it again bears reminding the reader that the absence of tadpole fossils does not equate to an absence of tadpoles but rather an absence of environments that were conducive to preserving them. There are also other options for temnospondyls. Metamorphosis occurs in a great number of different fashions across living animals, ranging from butterflies to tunicates, and it is not restricted to a transformation that always features aspects associated with amphibian metamorphosis such as a water-land transition or a change from having no limbs to having four. Butterflies, for example, go from squishy caterpillars with many legs to butterflies capable of flight and with exoskeletons (amongst other features not found in caterpillars). So it is quite possible that temnospondyl development does not look much like that of modern amphibians, particularly in groups that are not closely related to the modern groups. Larval temnospondyl specimens are well-known in the literature, although a number of them have often created longstanding confusion over whether they are truly the larvae of much larger temnospondyls (regardless of whether they move onto land) or whether they are relatively mature sub-adults to adults that remained small throughout their lives (this is called the "branchiosaurid problem" and will addressed at a later date). For example, seen above are photographs (on the left) and reconstructions (on the right) of larval individuals of the temnospondyl Sclerocephalus haueseri from Germany (Schoch, 2003). Adults reached a body size around 1.5 meters, whereas the entire skeleton of both of the individuals shown here was shorter than the skull of an adult. Large sample sizes that capture incremental size and morphology changes allows for us to get a better idea of when certain features appear or disappear during development (assuming, of course, that all specimens in the putative growth series actually belong to the same animal).

So from the perspective of having a larval form that lacks most of the ossifications found in adults, yes, there are temnospondyl "tadpoles," but they are not tadpoles in the sense that we see in modern amphibians, and there is no clear evidence that they underwent metamorphosis in the exact same fashion. Metamorphosis and other ontogenetic aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology will be covered in more detail in the future (maybe next week honestly). TLDR: yes there are temnospondyl "tadpoles," but they do not look like tadpoles of modern amphibians. Refs

David Marjanović

4/28/2019 01:36:28 pm

Tadpoles in any but the very widest sense are limited to frogs/toads: they represent a very early stage in development that has been expanded into a feeding and growth stage with a very elaborated cartilaginous skull, and is followed by a metamorphosis that is more drastic than in other extant amphibians. We do have some very early stages in the development of a few temnospondyls, but they're more like salamanders/newts at comparable stages than actual tadpoles. Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed