|

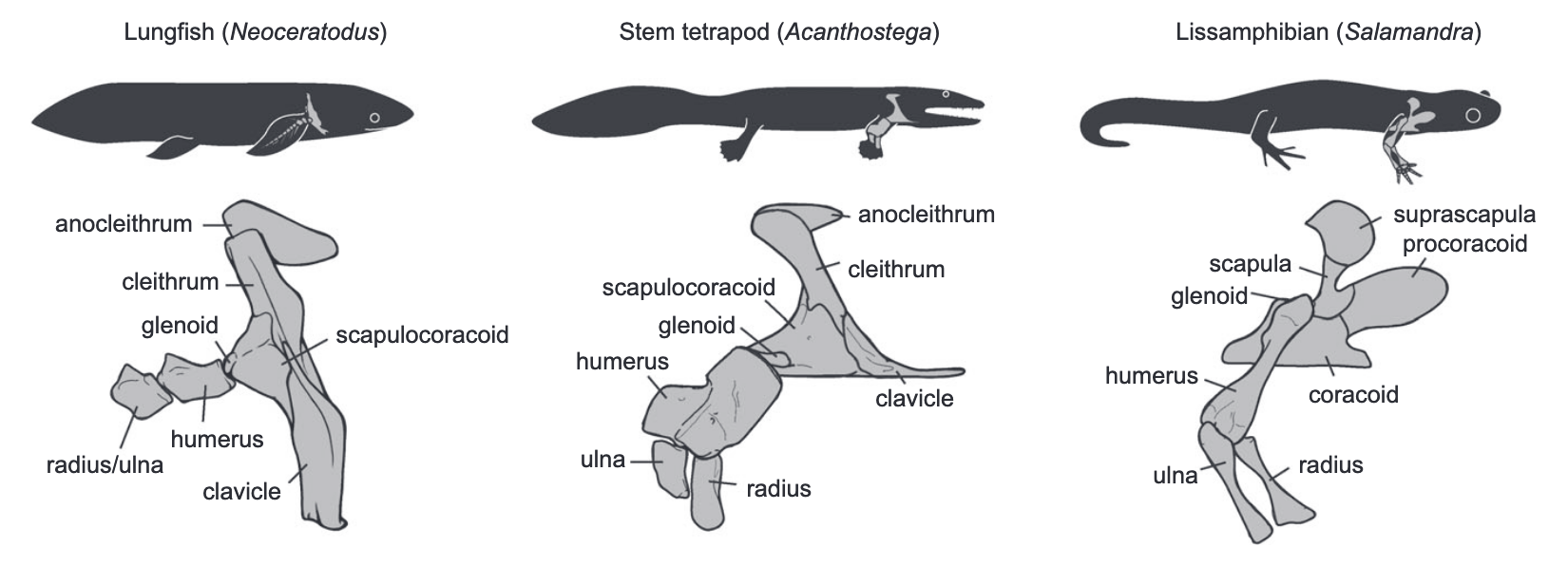

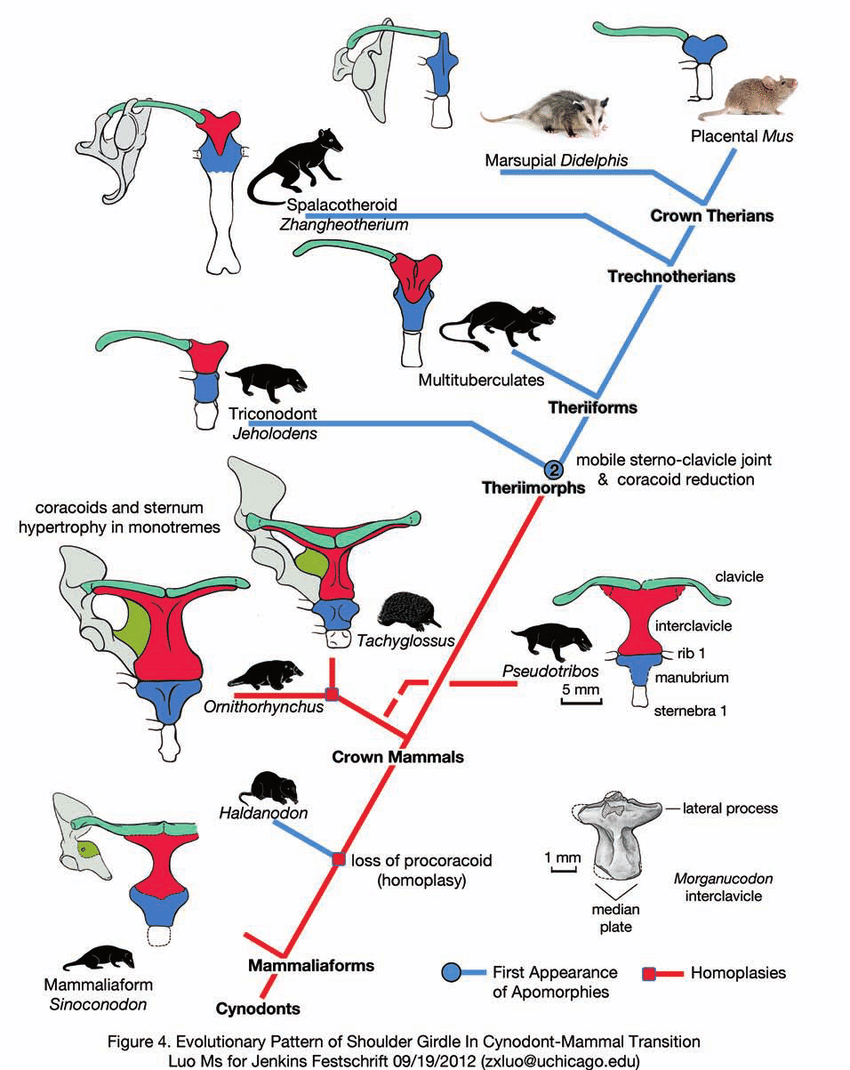

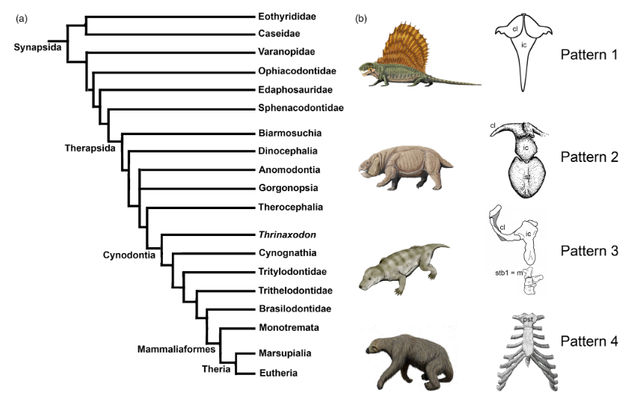

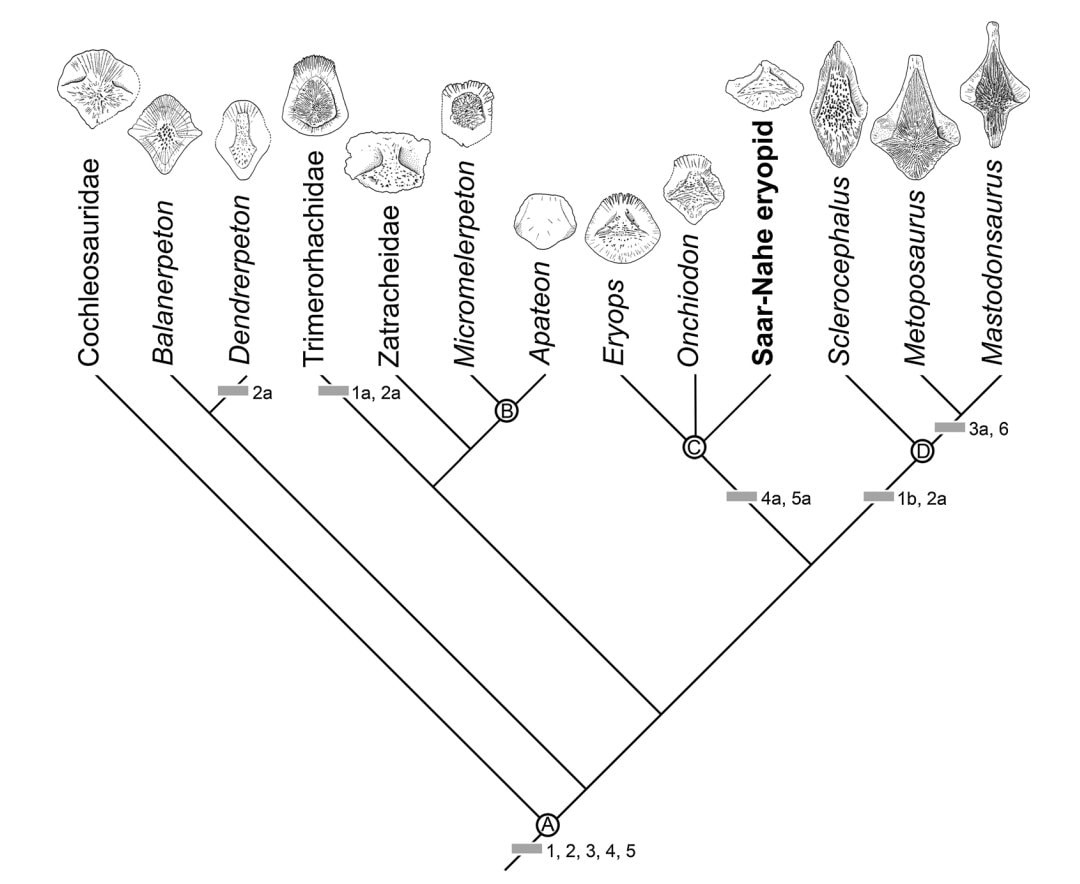

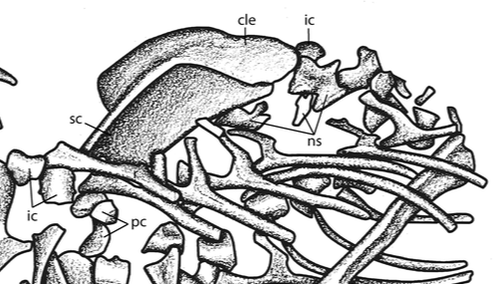

The limb gets a lot of attention because it's the part of the body in direct contact with the ground (or in the case of some animals, avoiding contact with the ground). But equally important is the apparatus that connects to the limbs - the girdles! What we call the shoulder girdle is scientifically termed the 'pectoral girdle,' while what we call the hip or the pelvis is termed the 'pelvic girdle.' This week's post will look at the pectoral girdle! Temnospondyls have four to five different elements in their pectoral girdle: the interclavicle, the clavicle, the cleithrum, and the scapula + the coracoid / a composite scapulocoracoid. Stem tetrapods (like Acanthostega in the middle below) have an anocleithrum inherited from our fishy forerunners, but this is absent in all temnospondyls. Conversely, some extra bones are found in modern amphibians (like Salamandra on the right below). Several of these will sound unfamiliar to people who only know mammals because we (and other mammals) lack cleithra and interclavicles.

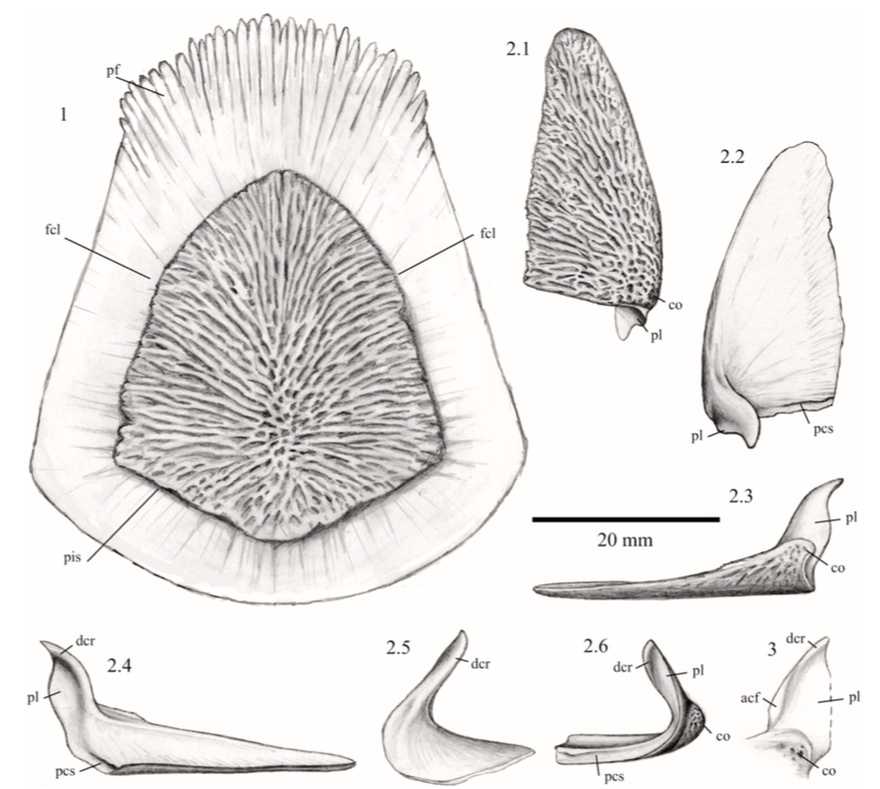

Clavicle The clavicle is one pectoral element still found in humans, but it looks nothing like what we see in temnospondyls. In humans, our collarbone is a long and slender bone with a slight curvature. The equivalent in temnospondyls serves the same function, connecting the shoulder (scapula) to the sternum/central part of the chest.

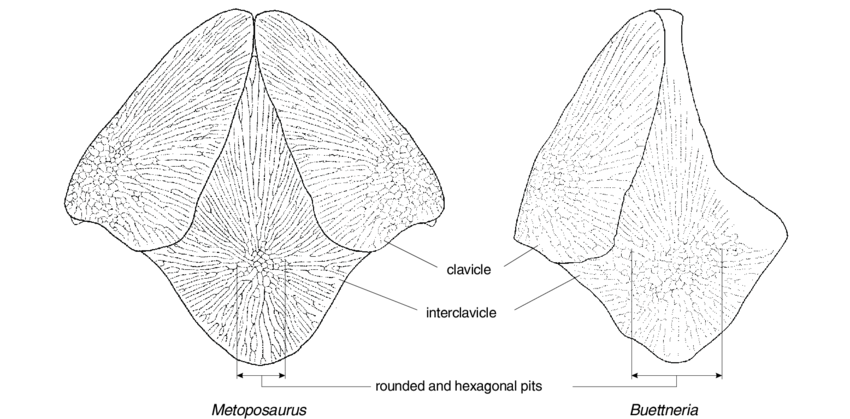

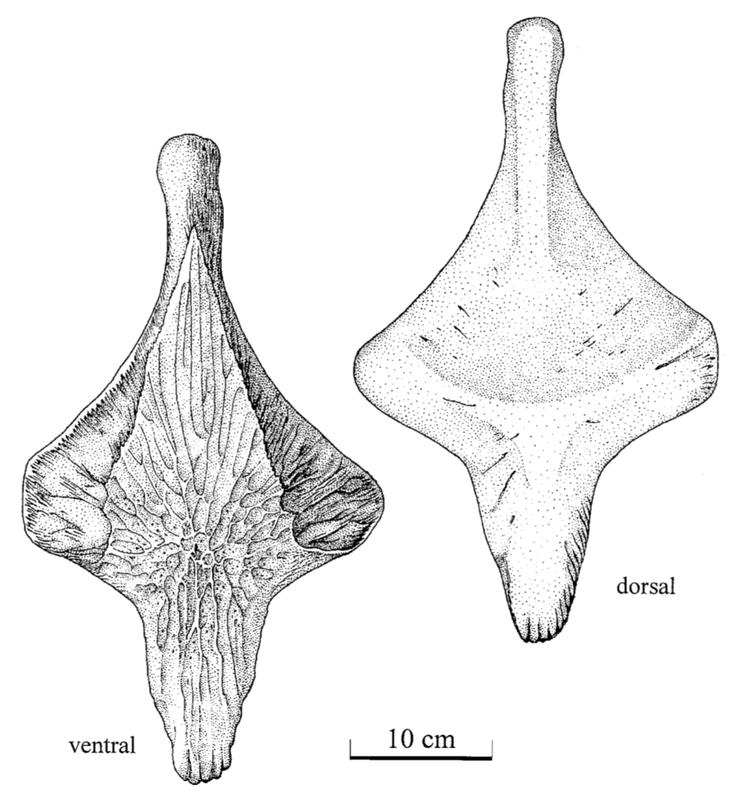

Interclavicle The interclavicle (which I'm told sometimes sounds like 'inner clavicle' when I don't enunciate) is the only unpaired element of the temnospondyl pectoral girdle. This is typically one of the larger elements and sits right under the chest in the position that we would call the sternum in humans. The interclavicle isn't super variable in shape, usually being diamond to rhomboidal, but it can be a little variable in whether there is a long process sticking forward or backwards. It is essentially entirely flat and plate-like. Because the interclavicle directly articulates with the clavicles, as seen below, any diagnostic features that can inform on the lifestyle of these animals are also likely found in the clavicle. These include the relative size and degree of ornamentation. While we often associate robust bones with terrestriality, too much weight can be bad on land, which is why terrestrial taxa tend to have proportionately smaller and lighter clavicles and interclavicles (the weight gets loaded on the scapula and the limb). Conversely, the massive (and often quite thick) elements of aquatically inclined taxa may have served as ballast, similar to how their internal bone structure is more dense (see last week's post).

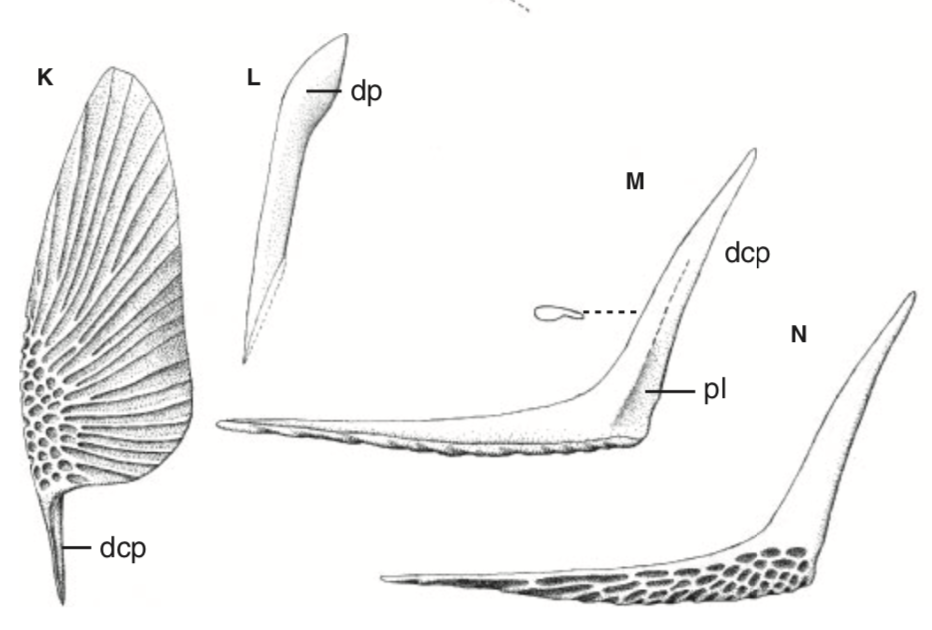

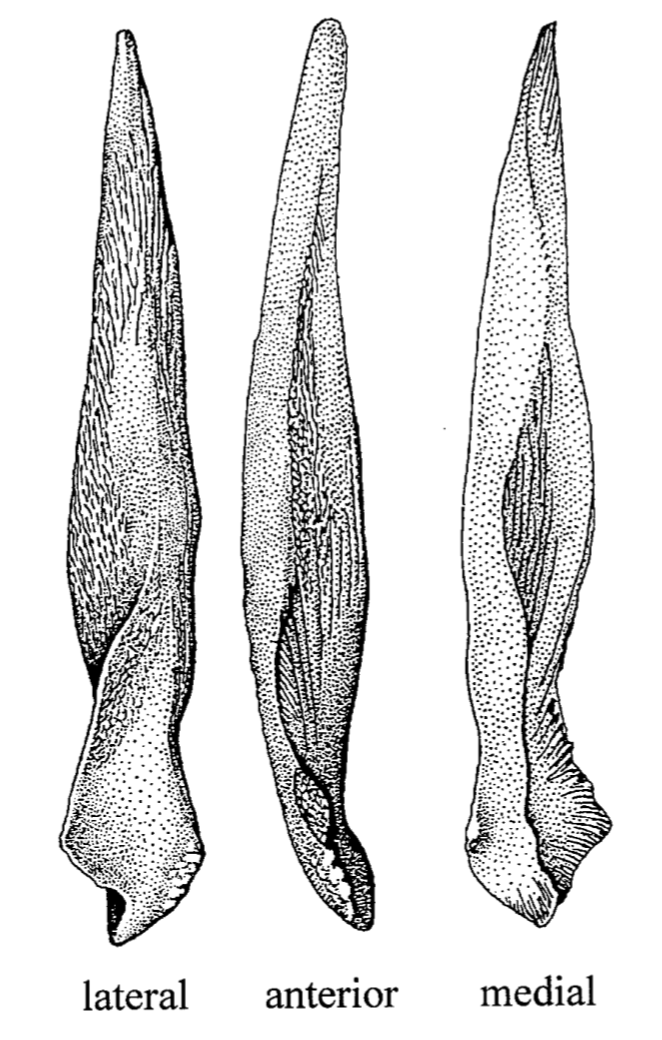

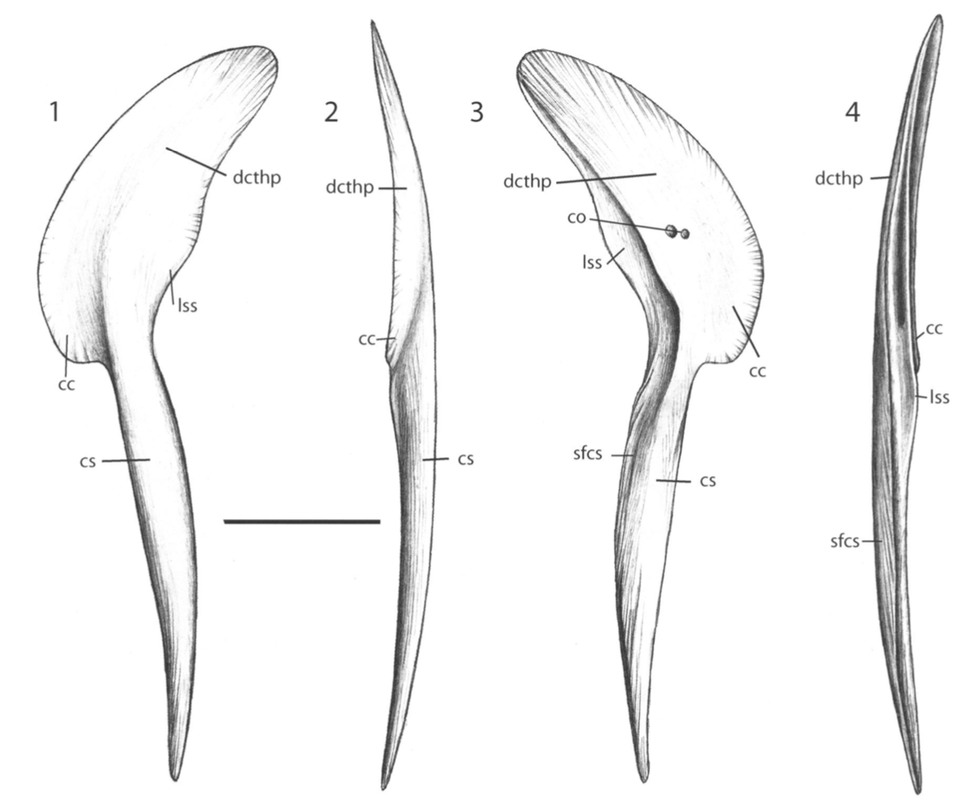

Cleithrum

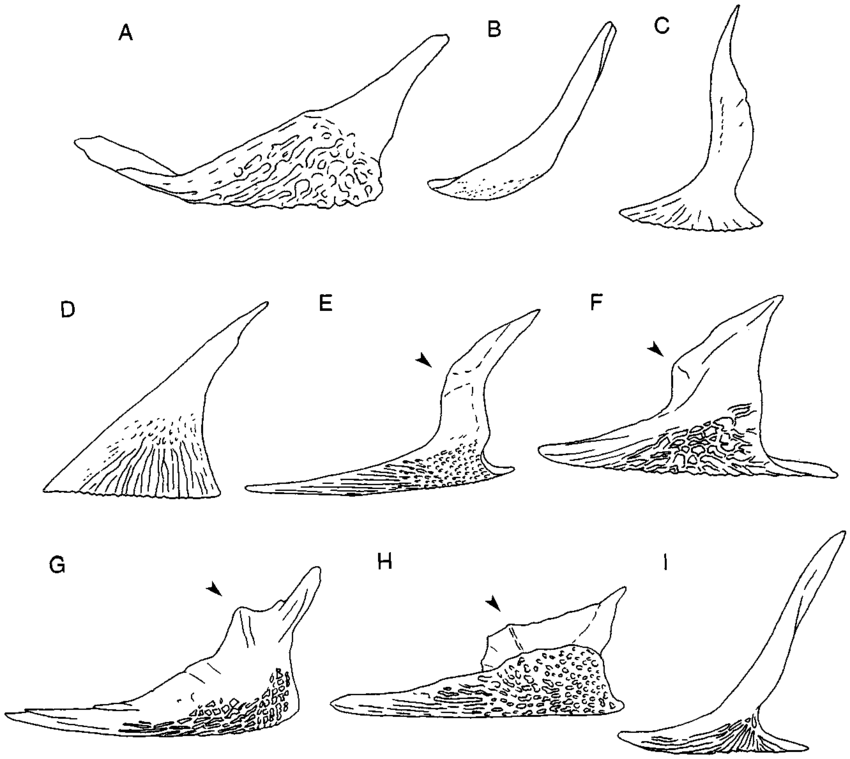

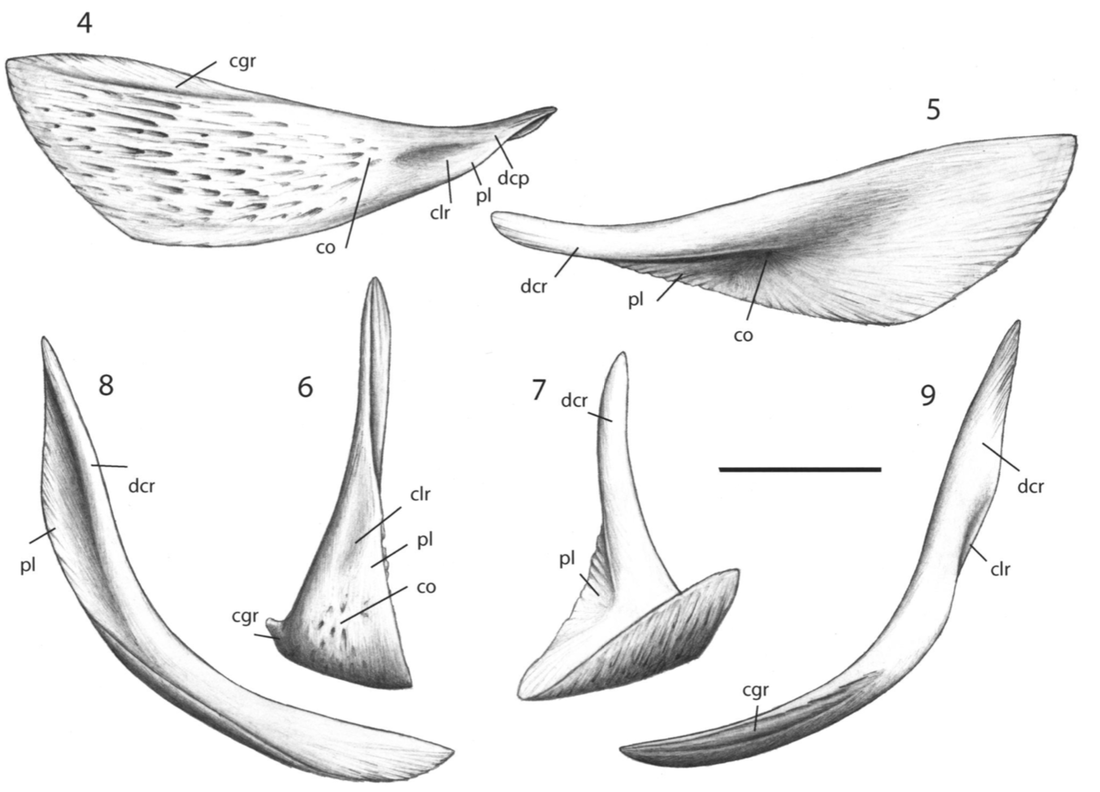

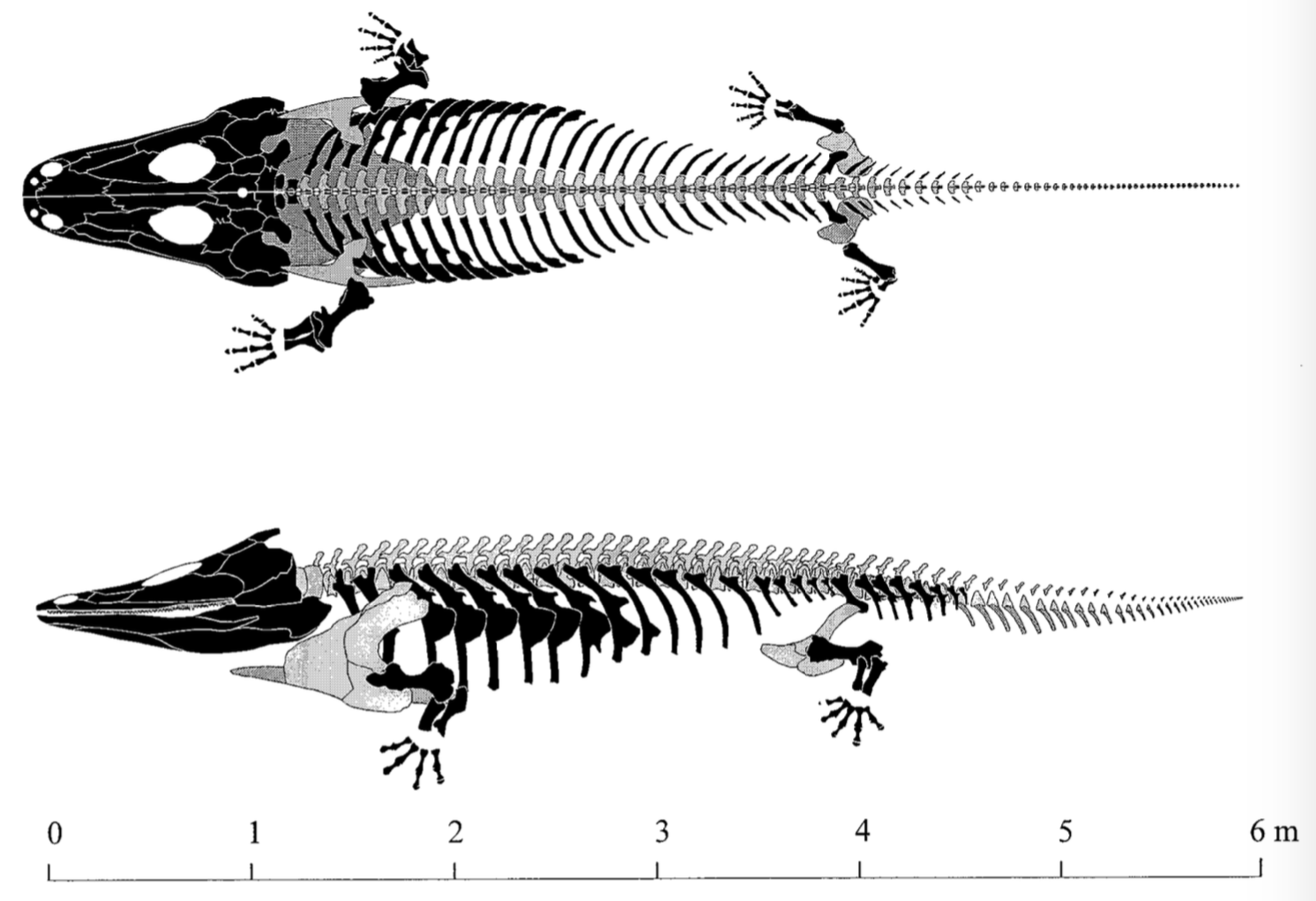

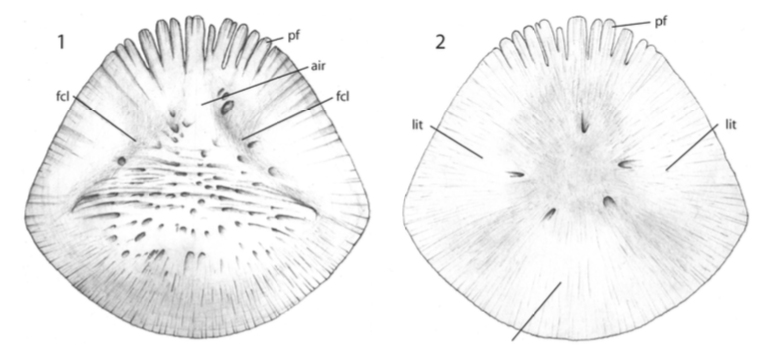

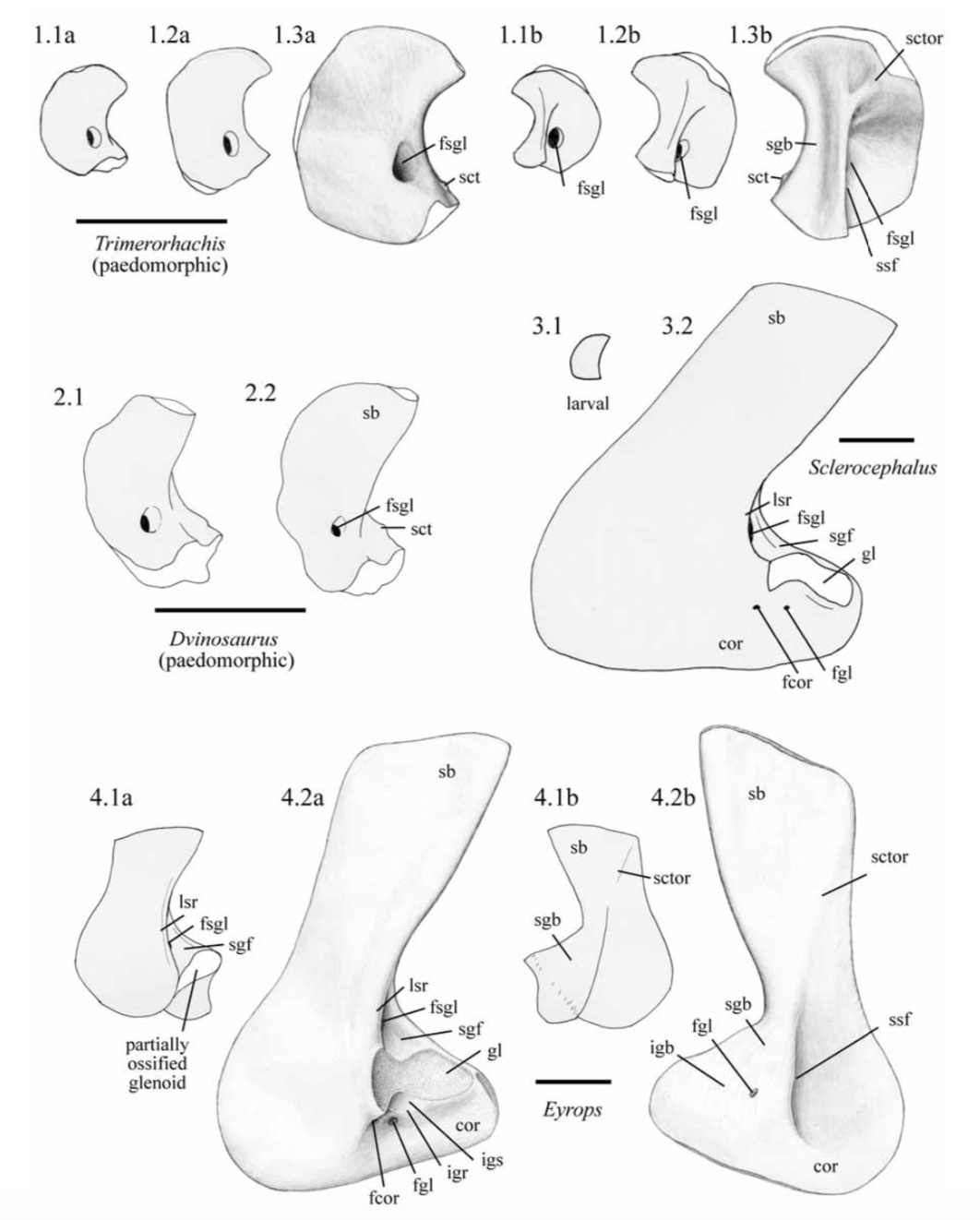

When you find a complete cleithrum, it is really easy to tell whether it belongs to a probable terrestrial temnospondyl or not. If it's a simple rod without substantial expansion, like Mastodonsaurus above, it likely belongs to an aquatic temnospondyl. Conversely, when the dorsal end is greatly expanded into a round plate-like process, like in Eryops below on the left (source: Pawley & Warren, 2006), or greatly expanded to form an L-shaped element that overlaps the dorsal margin of the scapula, like in an indeterminate dissorophid below on the right (source: Gee & Reisz, 2018), you probably have a terrestrial taxon. Whereas larger tends to correlate with aquatic lifestyle in the clavicle and the interclavicle, the cleithrum serves as both a support strut for the scapula and for muscle attachment, so a larger cleithrum is more important for moving around on land under gravity. Scapula + coracoid / composite scapulocoracoid

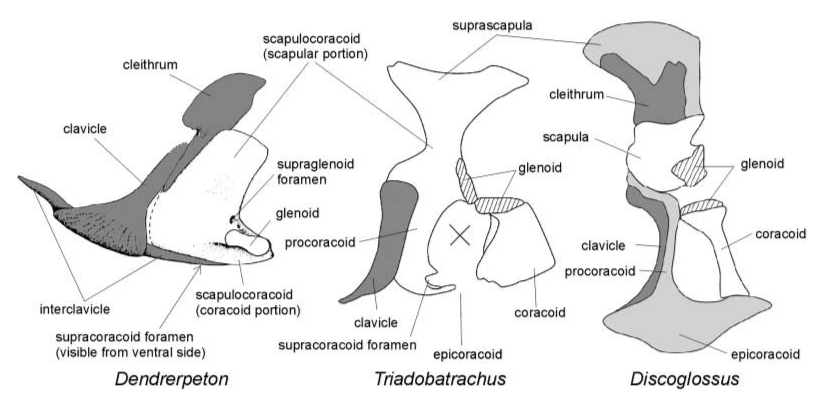

For reference, the temnospondyl anatomy is typical of early tetrapods but not of later tetrapods, and it's quite different in modern amphibians. In frogs, the scapula and coracoid are both ossified, like you can see in the early frog Triadobatrachus and the modern frog Discoglossus below (source: Havelková & Roček, 2006). Modern salamanders typically have distinct but contacting scapulae and coracoids. Caecilians of course have no limbs, so their pectoral girdle is similarly undeveloped. These are hardly the only differences either; there are other marked changes to other parts of this girdle. Summary The pectoral girdle shows a lot of the same signals that we see in limb elements, which is what you'd expect for something that sometimes has to hold up half of the animal's weight while moving about on land. Proportions are the easiest way to infer lifestyle, but especially the cleithrum and the scapulocoracoid can exhibit major morphological differences as well (if you can them). One big caveat, as it often is with postcranial bones, is that immaturity can accidentally be confused for underdevelopment, and those immature forms are not necessarily practicing a different lifestyle than the adults. This remains one of the big challenges in paleontology because the fossil record will always be incomplete, and some taxa are probably represented only by juveniles. How we differentiate them from adults that just happen to be similarly underdeveloped is a major part of my research. Up next week: the other girdle - the hips!

Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed