|

You've heard them called tusks; you've heard them called fangs. You've seen these terms with quotation marks and without quotation marks. They all seem to refer to these &#%!@*? big teeth in temnospondyls (and other early tetrapod friends). "But wait," you think to yourself. Aren't tusks like the things that elephants or warthogs have? And aren't fangs things that snakes have? Did extinct amphibians have features like that??

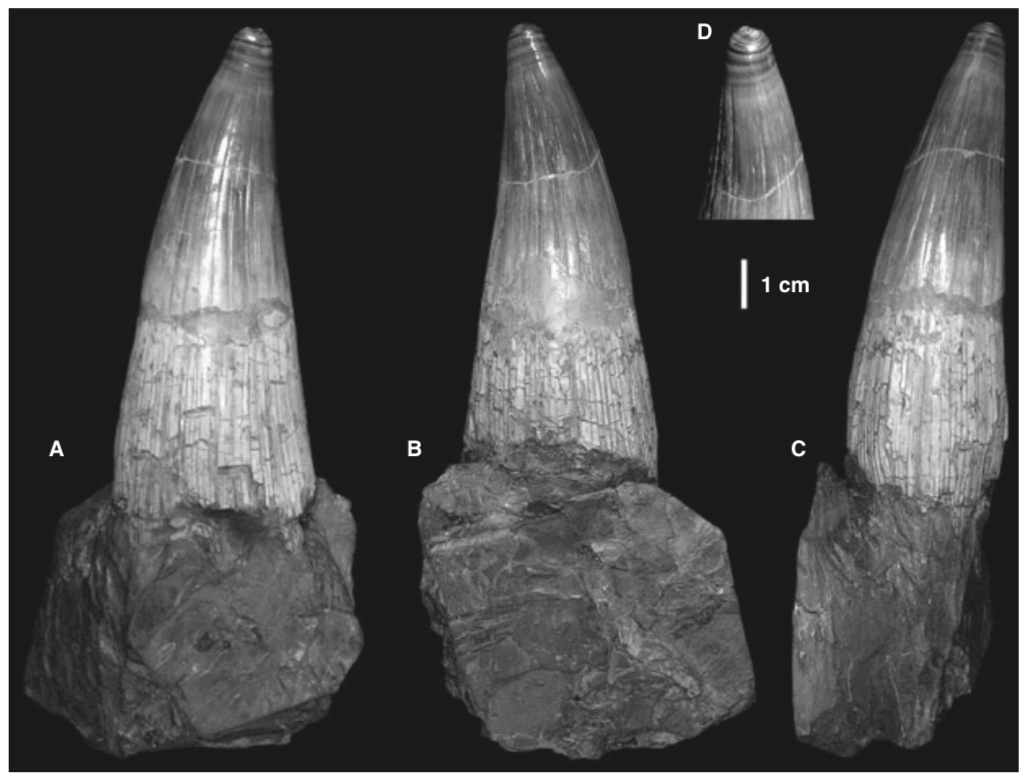

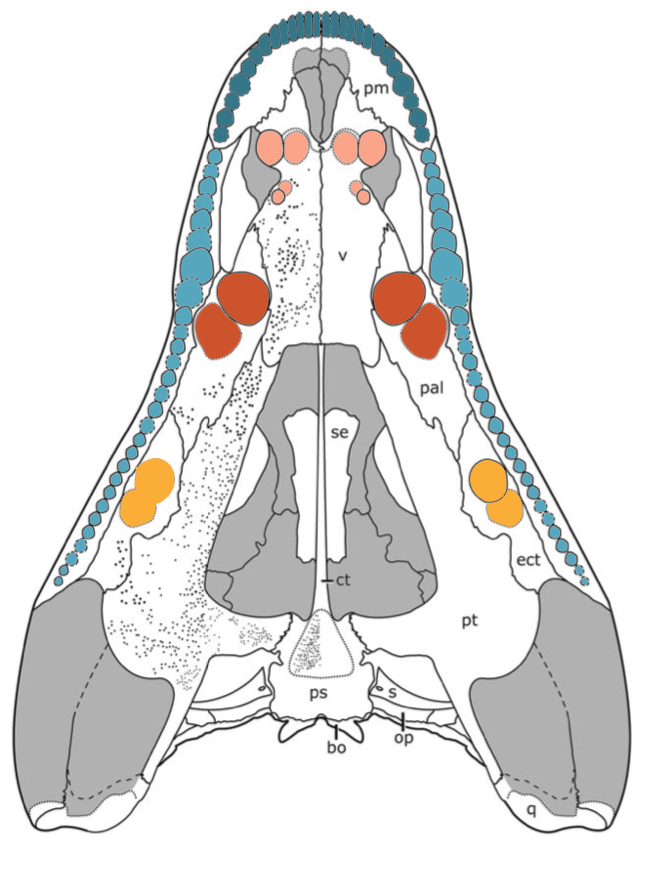

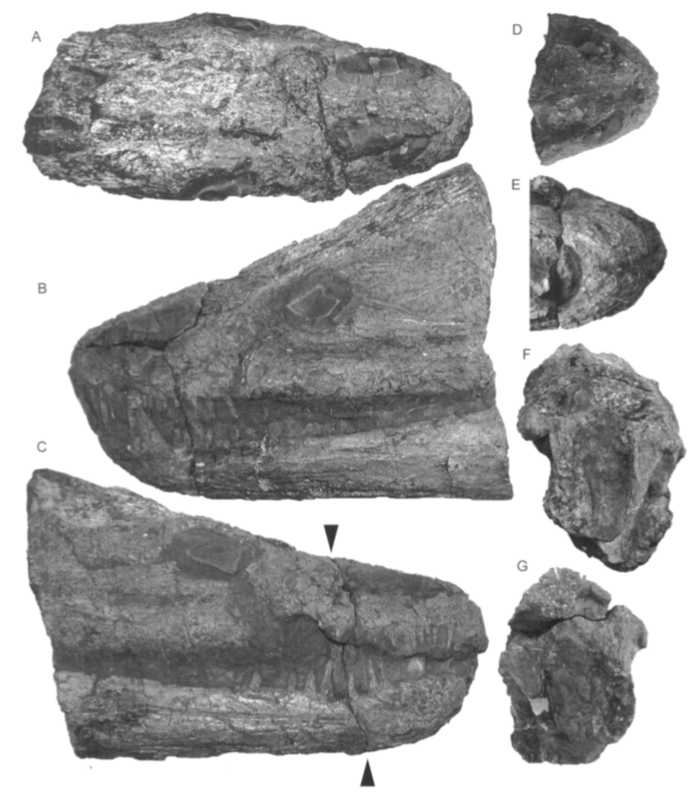

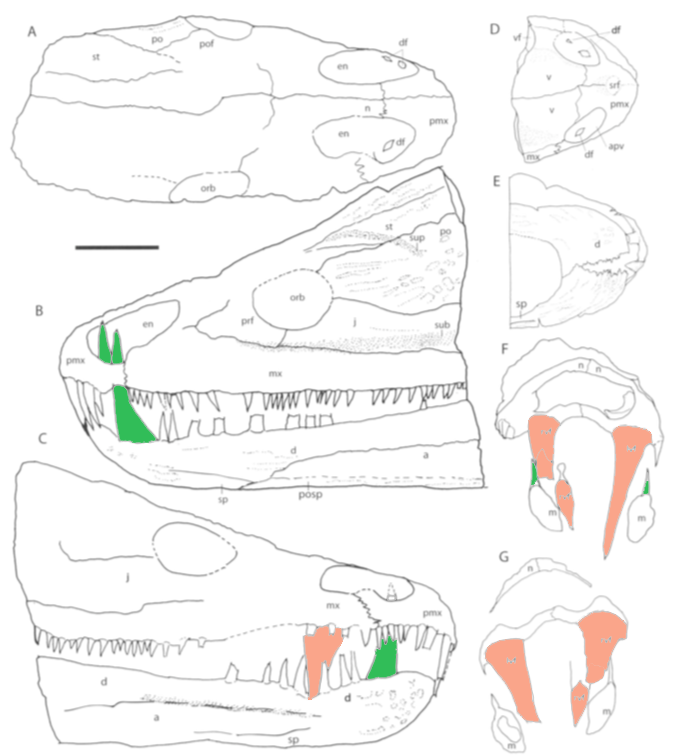

Why are these teeth so big? Presumably, the teeth are for prey capture, not for something like intraspecific competition (like tusks in warthogs, for example). How exactly they were used is a bit uncertain because feeding mechanisms of temnospondyls remain largely speculative and were probably quite varied (but see a lot of the work by Josep Fortuny; Witzmann & Schoch, 2013 for some non-tooth-specific examples). The fact that these enlarged teeth occur in temnospondyls of all sizes and across ecologies (e.g., aquatic versus terrestrial) might suggest some degree of phylogenetic conservatism (i.e. they retained it from earlier tetrapods and it wasn't sufficiently detrimental to be selected against) since there are major differences between vacuuming up fish in a river versus crunching hard-shelled insects on land. Similar to a lot of other animals with imposing teeth (like saber-toothed mammals and the narwhal), the most extreme (and usually the most mainstream) ideas are probably not very accurate (i.e. they're not crushing bone). The bone that the palatal teeth sit on in temnospondyls is very thin and probably couldn't handle major compressional stresses associate with jamming those teeth onto a hard surface. A lot of work left to do to sort this area of temno paleobiology... TusksTusks take a lot of strange forms, but they are typically regarded as a mammalian feature because they usually are modified canine teeth (modified incisors in elephants), a type of tooth used only with respect to mammals (the term 'caniniform' being used for canine-like teeth in other animals). Mammals (but also a number of reptiles and various extinct tetrapods) have more differentiated teeth (e.g., variable shape, function, implantation), often reflecting different feeding behaviours and processes within the mouth - this is referred to as heterodont dentition. For example, in humans, we have incisors, canines, pre-molars, and molars. Each tooth type is adapted for a specific and distinct function - incisors have thinner edges and are better for cutting, whereas molars have a broad surface for grinding and chewing (masticating). By comparison, many other animals, particularly "lower tetrapods" like fish and amphibians (including temnospondyls), have relatively homogenous teeth that differ mostly in size - this is referred to as homodont dentition. Virtually all temnospondyls' teeth are some permutation of cones with a single sharp point (monocuspid), which in part reflects the fact that their diets were much more restrictive than animals with heterodont dentition (e.g., omnivores). As a result, we don't have any categories for their teeth. We only differentiate them by their position (e.g., palatal [roof of mouth] vs. coronoid [an element on the jaw]). There are general size patterns correlated with position - palatal teeth are almost always distinctly smaller than marginal teeth, for example - but they're pretty vanilla compared to your average modern mammal. So as I noted above, calling the particular large teeth 'tusks' is one way to indicate which of the various teeth one is talking about in a temnospondyl. But are these actual tusks? Let's see what the internet dictionaries say about tusks (definitions only listed for the noun form):

Hmmm....so overall, no additional clarity gained. It should be noted that defining tusks as paired teeth isn't very good because that means that the tusks of narwhals and unicorns are not tusks. Narwhals occasionally have paired tusks, but it's quite rare, and I at least have never seen a unicorn with paired tusks. Someone should comment if they have (photographic evidence required). A recurring theme in a lot of these definitions is that the tusks are not just enlarged teeth, but that they project out(side) of the mouth. Because temnospondyl "tusks" didn't serve the same suite of functions as mammalian tusks, perhaps this is a good place to draw the line. WRONG! There's always some oddball out there, and in this case, there are a few temnospondyls whose mandibular "tusks" poke through openings in the skull. Yes, you read that right. The teeth are large enough to go through either the nostrils (Microposaurus, see below) or through extra paired openings in the snouth (some trematosaurs, mastodonsaurids). Probably the most helpful criterion is that tusks are constantly growing. They don't typically replace throughout life, although they can sometimes regrow if broken off provided the damage is limited to the crown (the exposed part) and not to the root (the embedded part). This is why tusks are typically more extensive (longer and sometimes more curled) in older mammals. As far as we know, temnospondyl "tusks" are replaced by just falling out and growing a new one, just like the rest of the teeth. FangsLike tusks, fangs are typically associated with particular animals, namely long and sharp teeth for prey capture in mammals, venom-delivering teeth in some snakes, and the things that look like teeth in spiders. In most cases, these are functions more readily associated with predation compared to tusks, which are primarily for almost anything else. Back to the online dictionaries:

Does it really matter what you call them? Does (did) the temnospondyl care? Unlikely. Does the average person? Definitely not. Linguistically speaking, there's no language police going around telling you what to use and what not to use - it would honestly be a lot easier to sort this all out if there was some arbitrary arbiter of terminology. From a practical standpoint, I do think it's important to be consistent in terminology when possible though, firstly because it implies homology (shared feature due to shared ancestry) to a certain degree (e.g., the femur is the same ossification in all tetrapods), and secondly because it makes it a hell of a lot easier for people unfamiliar with the system / structure to think they're comparing apples and oranges when it's really just different apples that are named as "apples" and "oranges." "Tusks" and "fangs" are pretty easy to sort out, but other names for specific parts of a certain element (e.g., semilunar curvature of the squamosal) can be harder to figure out when they're inconsistently applied and hard to discern from a label that could be pointing to some other structure or the element as a whole. Can't really do anything about the 18th-early 20th century when lots of fun and outdated terms were used (to say nothing of terms in languages other than English), but I do think it's something important to strive for. So what do I prefer? In my mind (and probably in a lot of other non-temno workers / non-scientists), fangs are primarily involved with prey capture, although that doesn't have to be primarily for inflicting serious physical injury (e.g., venom delivery in snakes). Seems about right with what we'd predict in temnospondyls. On the flip side, tusks are widespread in herbivorous, not carnivorous, mammals, and they are involved with a variety of functions that may be only tangentially related to feeding (e.g., digging) or totally unrelated (e.g., social signaling and competition) that often relate to the fact that they project outward compared to normal teeth. Therefore, I would say that 'fang' is more appropriate in terms of how we perceive the differences between these terms colloquially, since etymological origins and definitions are not going to help us out very much. To be honest, I've never paid much attention to which one I used in my publications, but after doing a quick check, that's apparently because I've only used 'tusk' once, and I put it in quotation marks, so my own notions of terminological consistency are apparently stuck in my psyche... Refs

David Marjanović

2/14/2019 12:14:09 pm

I did not know about Microposaurus. It leaves me speechless!

Andreas Johansson

2/14/2019 01:37:40 pm

I'm fairly sure that uniCORNs have horns, not tusks.

David Marjanović

3/7/2019 11:46:12 am

Unicorns are supposed to have horns, but they're generally modeled after narwhal tusks; the latter of course used to be sold as the former. Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed