|

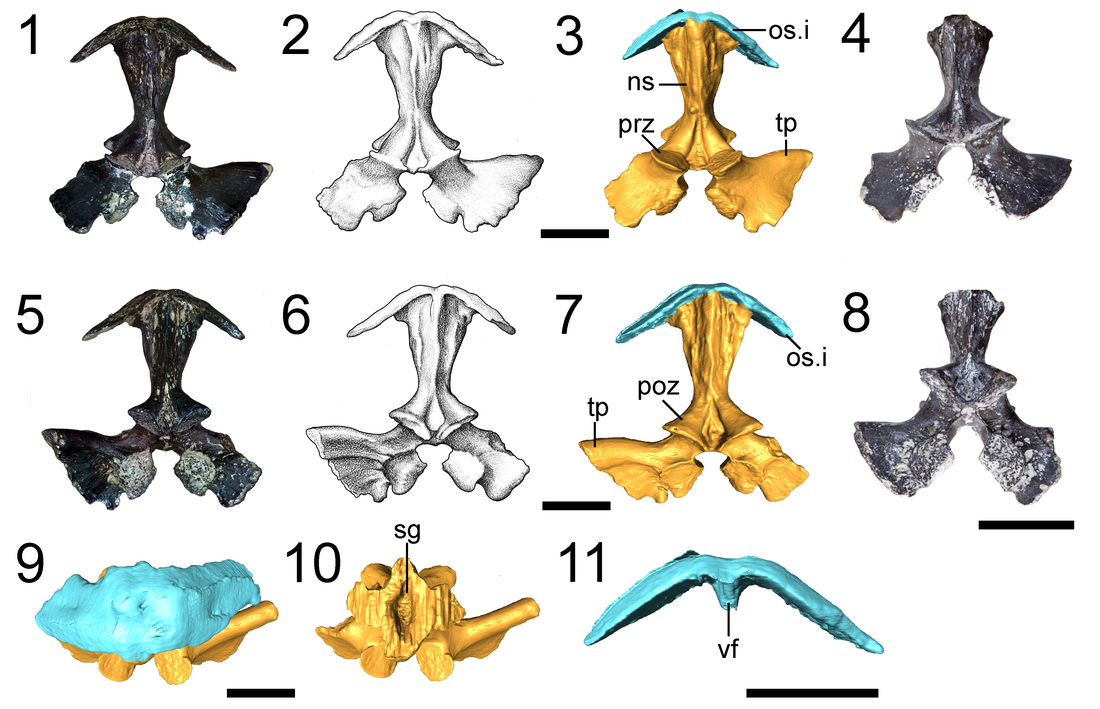

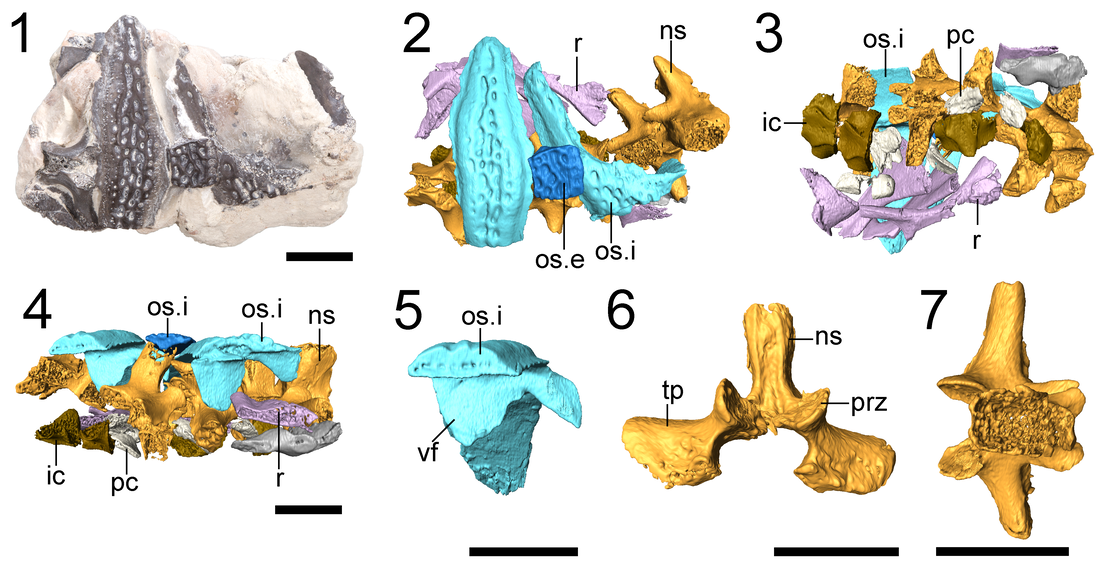

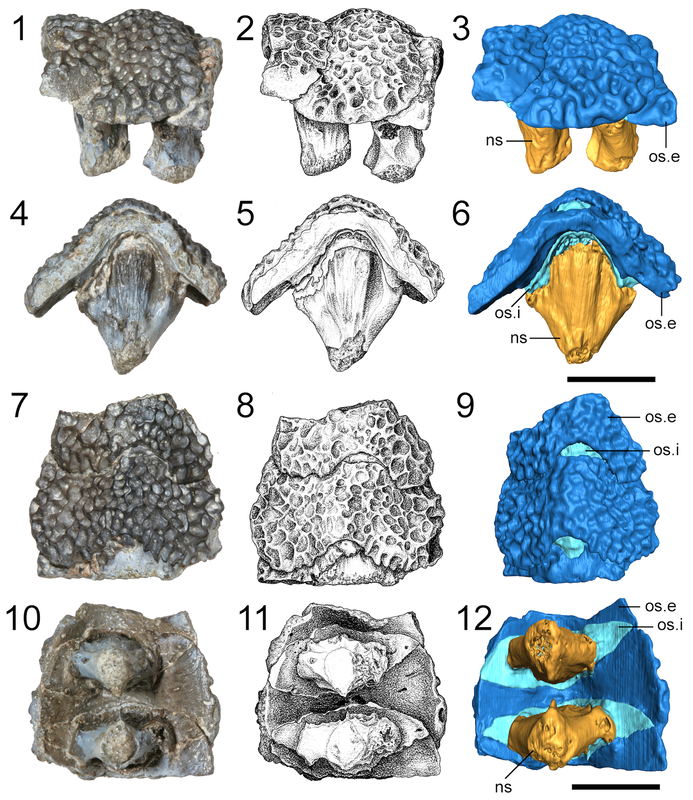

Title: Dissorophid diversity at the early Permian cave system near Richards Spur, Oklahoma. Authors: B.M. Gee, J.J. Bevitt, R.R. Reisz Journal: Palaeontologia Electronica, article 22.2.46 Link to paper - this is an open access paper than anyone can read! Summary for non-scientists Despite the above image including a lot of CT data, this is not really a CT paper. It is, however, a metaphorical smorgasbord of dissorophids - 21 specimens reported for the first time here, distributed across at least 4 genera, all from Richards Spur. Dissorophids are the ones with armour along their backbone, which you can see in the above image (os.i = internal osteoderm). We've got new skulls, new skeletons, and new data! The point of this paper is largely to summarize what we know and what we have from the locality, which is quite a lot (coincidentally we've got even more in the last few months since this paper was accepted). This plethora of new specimens gives us a lot of new anatomical information, including internal data that we gleaned from the CT data, and also expands the known diversity at Richards Spur by an additional two taxa that were previously only known from Texas. Even more Cacops... I think we find a new Cacops specimen every year that I've been here. The skull of Cacops morrisi with associated postcrania from the anterior part of the skeleton (below on left) is the sixth that we've published on (fourth for me) and the seventh in existence. Normally, it would be a pretty remarkable specimen in terms of completeness and the presence of articulated postcrania, but a comparably sized specimen that we previously published on (Gee & Reisz, 2018a; JVP) is even better preserved than this one, so it doesn't contribute as much new information as you might think. The Cacops woehri skull (below on right) is the third published one and somehow got perfectly sheared straight down the midline. I looked for that other half, but it might very well be 2" farther down (the block is about 6" thick), and there was too much other stuff that would have to be destroyed to even explore. This specimen is distinctly larger than the holotype (which is split in a similar fashion) and about the same size as the second specimen (which was just the back of the skull).

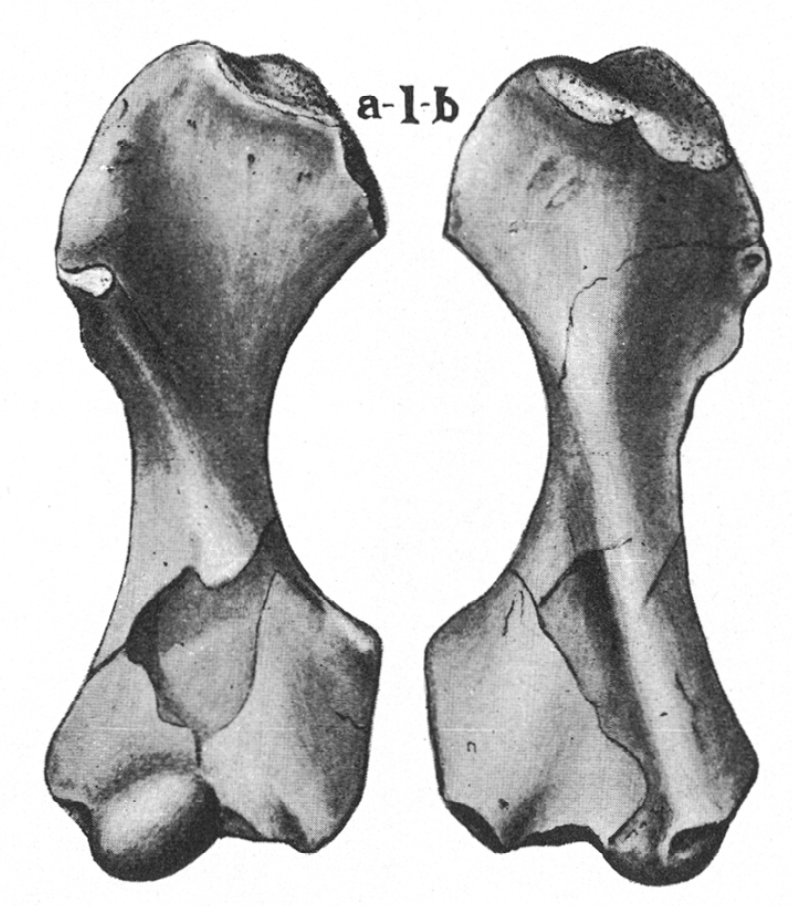

So conveniently, about a month after the paper was published, I was at the Field Museum and found Williston's specimen! Of course, it was sitting in one of those drawers way high up that stored random miscellaneous amphibian and reptile bits. Above you can see the photo of me holding the specimen up against the image of the Richards Spur animal. Unfortunately, nobody else has a precise idea of what the animal is either, so the precise taxonomy remains a mystery... We found a few more fragments that we think go to this animal from Richards Spur, so the Field Museum specimen is also included in there as a supplement.

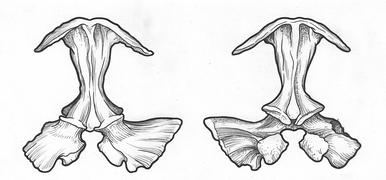

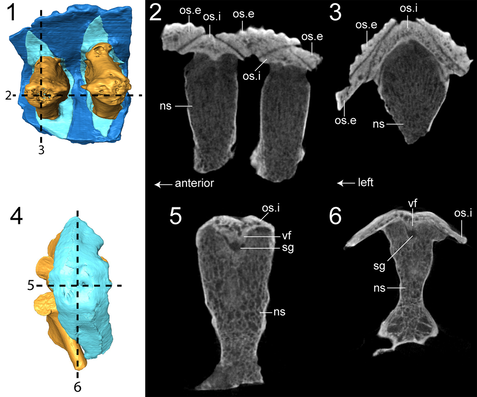

Furthermore, only dissorophines and derived eucacopines are supposed to have two series of osteoderms. This has led previous authors to conclude that the double series evolved independently in both of these dissorophid subfamilies (Schoch, 2012), which would explain the various differences between the osteoderms of these two groups. However, we also identified what appears to be a very clear double series in what is supposed to be an early diverging (basal / 'primitive') dissorophid, Aspidosaurus (see 1-3 in the first figure of this section). Compared to dissorophines and eucacopines, the internal osteoderm is disproportionately smaller than the external osteoderm and largely covered by it. This raises a lot of questions about whether this really is Aspidosaurus (by all other accounts it's indistinguishable from other Aspidosaurus material), in which case it could be that the double series wasn't identified by previous authors for any number of reasons (or doesn't occur in everything assigned to Aspidosaurus, or only occurs in part of the vertebral column, or....well there are lots of options) or if it is something very close to Aspidosaurus but not Aspidosaurus proper. Part of the problem here is that the type species of Aspidosaurus was only known from the holotype, and that was destroyed in World War II...  I also got a sweet tattoo out of one of the specimens we described for this paper (no I didn't get it just because it was a temnospondyl). The ink was done by E.K. Chan, who is a phenomenal person and artist; you can see the illustration they did for me to the left and check out their Instagram page here! TLDR: Lot of new dissorophid material from Richards Spur - (1) additional anatomical details that further inform on the taxonomy of previously known taxa; (2) new reports of taxa previously known only from other sites; (3) sweet CT data; (4) tattoo for Bryan. Refs

Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed