|

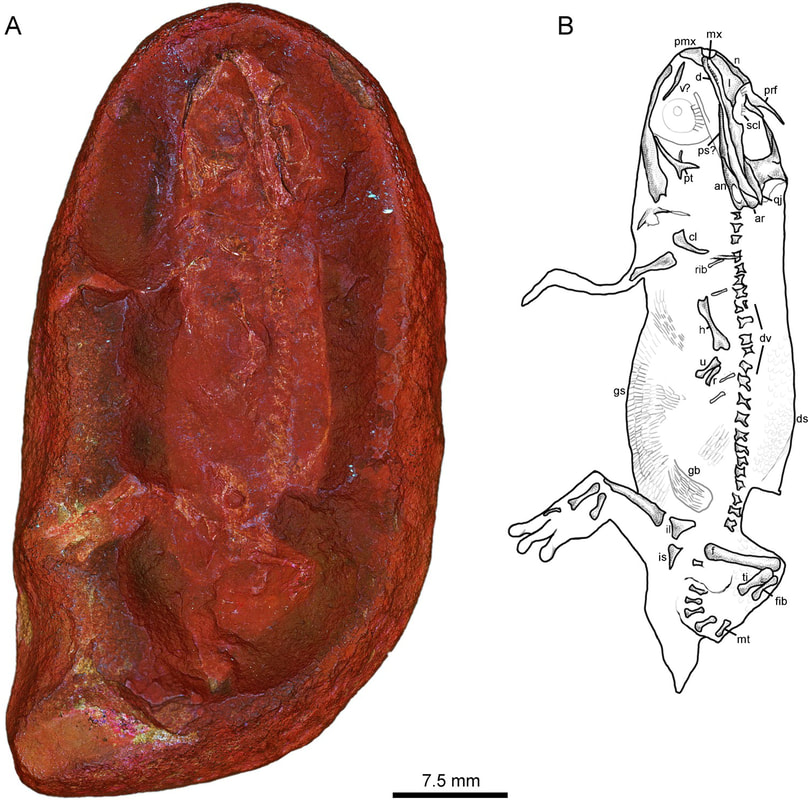

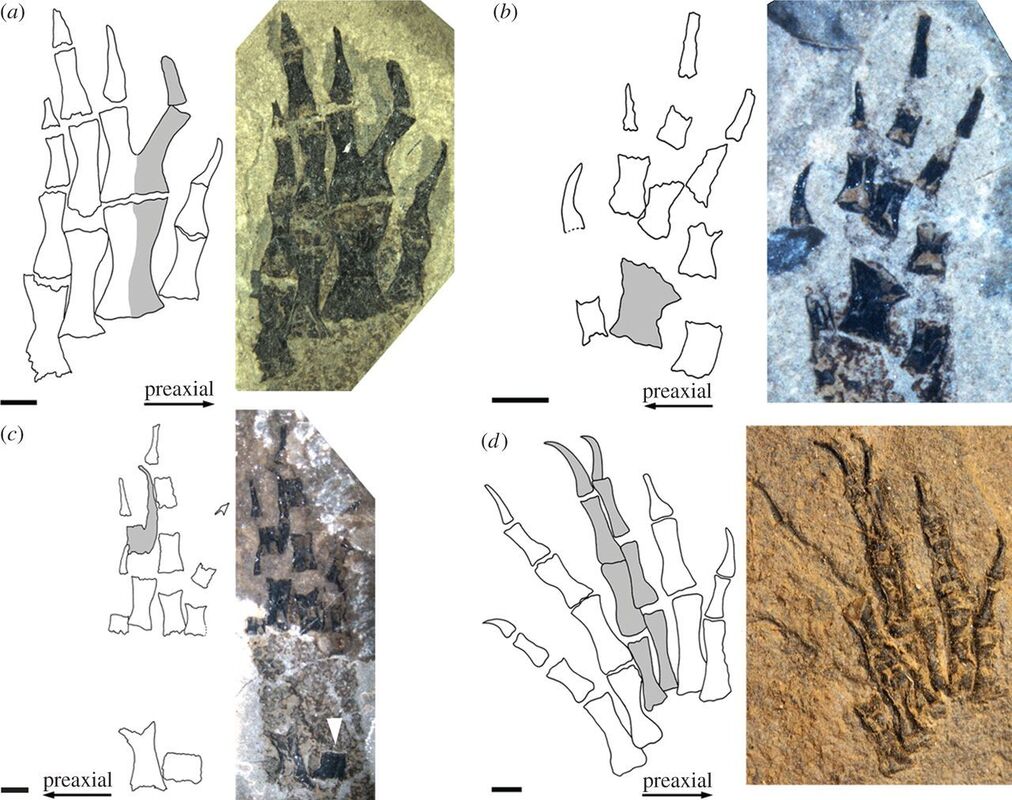

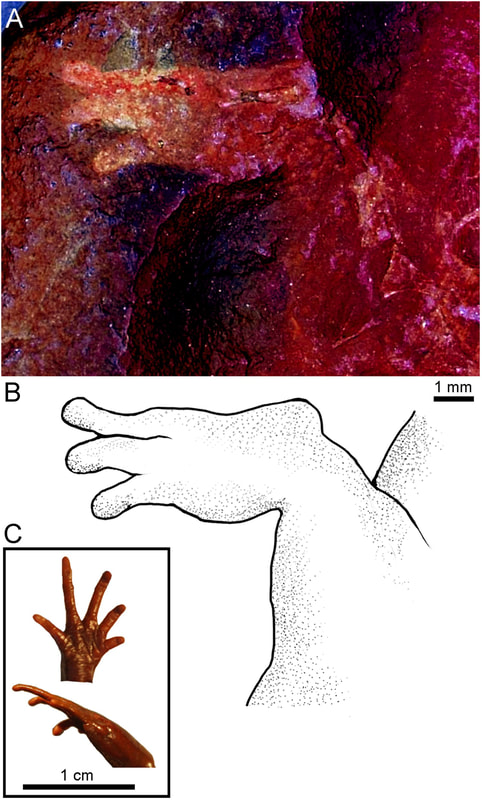

Title: Lissamphibian-like toepads in an exceptionally preserved amphibamiform from Mazon Creek Authors: A. Mann; B.M. Gee Journal: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology e1727490 DOI to paper: 10.1080/02724634.2019.1727490 Note: this paper came out on Wednesday, but it took a little while to get around to the blog post. As you can imagine, it's a little hard to write a blog in the middle of a pandemic. I actually plan to try to rev things back up in a week or two after I finish a bunch of problem sets for my stats classes, so stay tuned... General summary: Late Carboniferous Lagerstätte (fossil sites with remarkable preservation) are incredibly important for our understanding of the early evolution of many tetrapod clades. Mazon Creek in Illinois is one of the most famous Lagerstätte in North America and has produced a slew of both vertebrates and invertebrate material of great interest to paleontologists across the board (this is also where the famed Tully Monster comes from). The tetrapods have been studied by some of the most preeminent Paleozoic workers, including Moodie, Gregory, Watson, Westoll, Olson, and Baird, as well as by living paleontologists such as Jason Anderson and Andrew Milner. Preservation at Mazon Creek occurs in nodules that can be cracked in half to hopefully reveal a marvelous fossil within (or just a boring clay ball). Not only do these nodules often preserve complete, articulated skeletons, but they often preserve soft tissue structures (which is how we get a lot of records of squishy invertebrates). Here we describe a nice amphibamiform specimen (recalling that amphibamiforms are widely hypothesized to be on the lissamphibian stem) that preserves the oldest (quite possibly the only) record of toepad ('toe pad' with a space?) structures in a temnospondyl that superficially resemble those of lissamphibians. Arjan's doctoral dissertation is on Mazon Creek (the amniotes mostly); talk to him (arjanmann[at]cmail[dot]carleton[dot]ca) if you wanna know more about the exciting stuff going on!

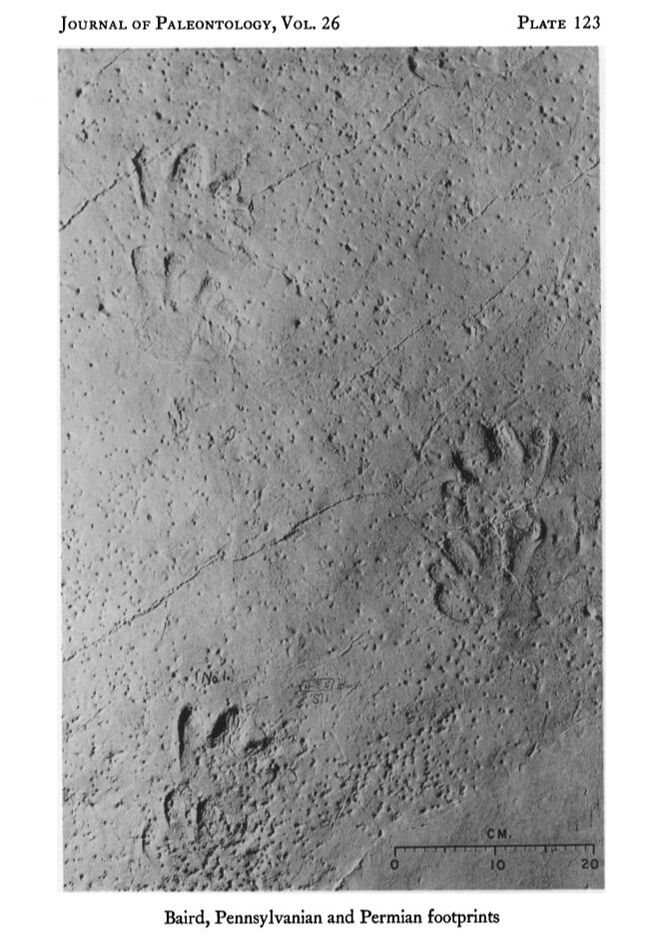

Remarkable soft tissue preservation isn't the only way to get information about the soft tissues of course. It has long been known that temnospondyls have chunky digits based on trackways that preserve some fat impressions, and there are a lot of temnospondyl ichnotaxa (identified usually by the presence of only four fingers on the hand) that have been reported in teh literature. Limnopus (figures from Baird, 1952) is one of the best-known ones and can be seen below. However, not surprisingly, we rarely get the soft tissue preservation except in aquatic taxa, which are not the ones making these types of tracks; preservation in terrestrial taxa is even less likely.

Refs

David Marjanović

5/10/2020 06:24:44 pm

It does actually look like Amphibamus. Contrary to the claim you copied, Amphibamus – specifically the neotype – does have 20 presacral vertebrae (Daly 1994); and given the squished preservation I have to doubt the skull shape can be reconstructed well enough to tell if it's different.

David Marjanović

5/10/2020 06:28:15 pm

"Schoch RR. 2019." Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed