Welcome to the blogIf you found your way here, you are probably only tangentially familiar with temnospondyls, having made their acquaintance through one of the following avenues:

What can you expect from this blog? This blog will (or hopes to): teach you more about temnospondyls than you ever wanted to know. It may include some animals that are not temnospondyls, but they will (probably) not fall too far from the tree. Content is more or less anything and everything that we know about these weirdos, primarily synthesizing what we know (but also with some personal opinions here and there). It is geared towards a general audience but may require some extra reading if you haven't taken biology in a while and does include highlights of current temnospondyl research. I don't know everything about temnospondyls, but hopefully you'll learn a thing or two! Current goal is weekly posts on #temnospondyltuesday. Temnos 101Here's the five most common FAQs I get about temnospondyls (seriously these are the most common ones):

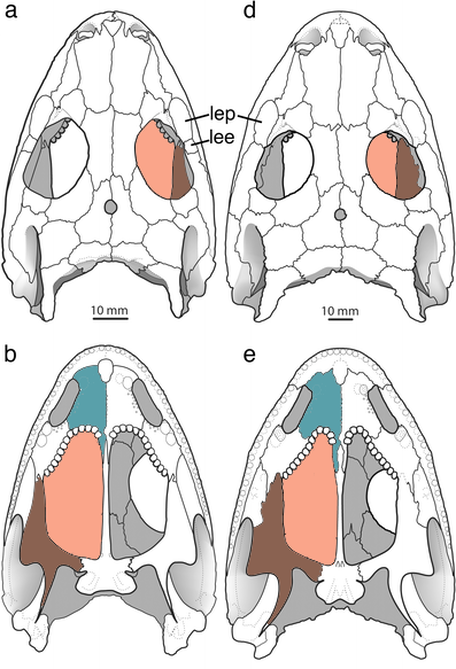

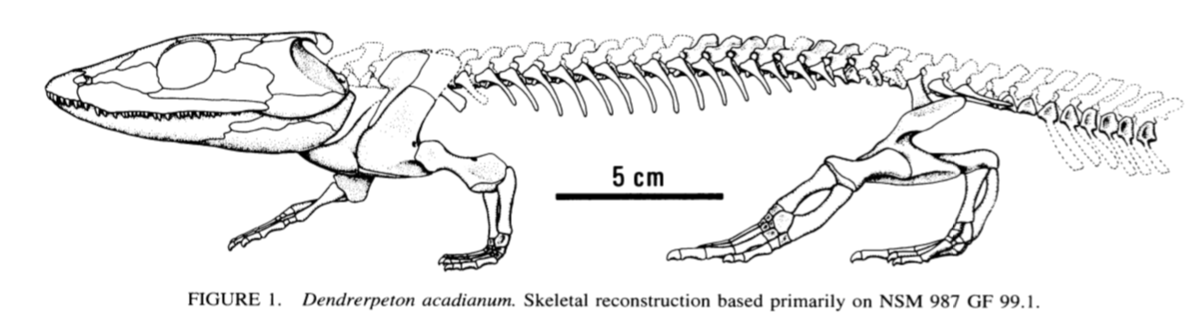

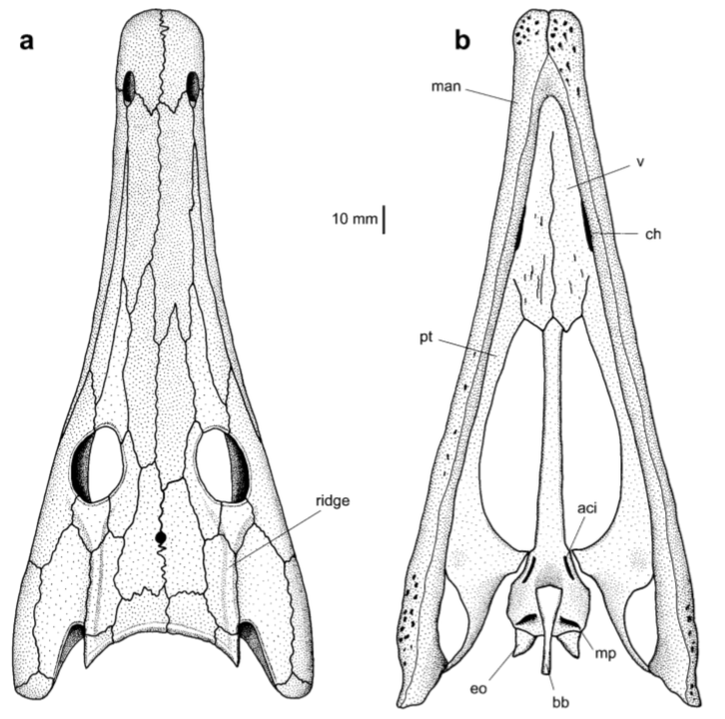

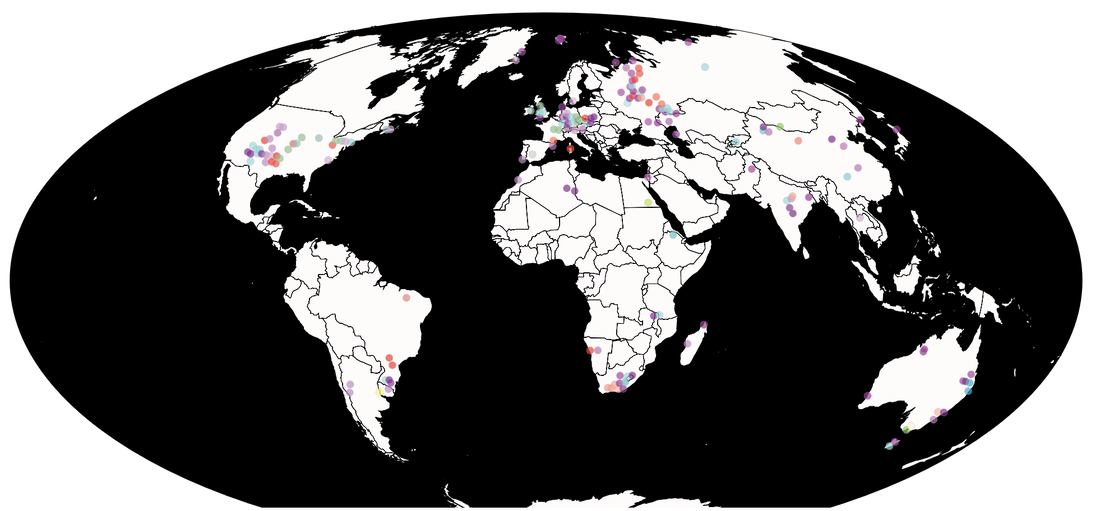

What are temnospondyls? If you want to get technical, they are non-amniote tetrapods, which is to say that they lack a special membrane called an amnion that is found in amniotes (reptiles, birds, mammals) that mitigates water loss of a developing embryo. The only living non-amniote tetrapods are amphibians, like frogs and salamanders. The name 'temnospondyl' comes from two Greek words, temnein ("cut") and spondylos ("vertebra"), which refers to their vertebra being made of three distinct elements that are not fused to each other (pleurocentrum, intercentrum, neural arch + spine), and was erected in 1888 by Karl Alfred von Zittel. It took a little while for the name to become widespread, but it eventually replaced more outdated classifications and groups (topic of next week's post). The multipartite vertebra is not unique to temnospondyls (most classification systems made in the 19th century haven't held up too well in the modern day), but there is a unique suite of other features that distinguish them. What are they most closely related to? Among modern animals, temnospondyls are considered to be closest to modern amphibians (called lissamphibians). In fact, there is a general consensus that lissamphibians are temnospondyls, and temnospondyls are often referred to as 'amphibians' in the primary literature. A lot of other extinct tetrapods are also called 'amphibians,' but temnospondyls are the real deal (at least according to most people). Now temnospondyls are not frogs, salamanders, or caecilians. A lot of things have happened since lissamphibians branched off and started their evolutionary meander to their present state. But this suggests that in the same way that we regard birds as living dinosaurs, modern amphibians are probably living temnospondyls. There is not the same degree of consensus regarding the origin of modern amphibians, particularly because their fossil record is not as good as that of birds, but that's for another blog post. What did they look like? Temnospondyls were originally mistaken for reptiles because they sure didn't look like any amphibian that anyone in the 19th century (or 21st century) had seen. The first temnospondyl (and many subsequent ones) include the same Greek suffix -saurus (meaning "lizard") in their name that also contributes to the name of many dinosaurs. The colloquial term 'crocomander' (crocodile + salamander) has often been used to describe some temnospondyls, and particularly for the aquatic ones, is not a bad approximation. Many of them had long skulls like crocs, long tails like crocs and salamanders, and the physiology of modern amphibians in many regards. Some temnospondyls actually had very narrow, elongate snouts just like crocodiles (see Archegosaurus above)...but evolved this feature tens of millions of years before crocodiles of any kind showed up, let alone aquatic ones with similarly long snouts. Others had very broad and short parabolic skulls. Some were flat as a pancake (okay, a really big pancake), and others were modestly tall. The suite of features that distinguish them are fairly technical for anyone without a basic anatomy background (see Schoch, 2013 for the full list), but the most prominent feature is these large openings in the roof of the mouth. We called these interpterygoid vacuities (between the pterygoid bones; see below), and they would have been covered in a flexible membrane. The function of these openings isn't fully resolved - they are very rare in other tetrapods (certainly not found in humans), but breathing assistance, eyeball-mediated swallowing like in modern frogs (video if you have no idea what I'm talking about), accommodation of jaw muscles, and stress distribution during feeding have all been suggested. Lots of cool recent research (e.g., Fortuny et al., 2011, 2016; Lautenschlager et al., 2016; Witzmann & Werneburg, 2017) has tested these ideas.  Illustrations of the early Permian temnospondyl Cacops morrisi from Oklahoma. (a) and (d) are in dorsal profile, and (b) and (e) are in ventral profile, showing the roof of the mouth. Red = the interpterygoid vacuity (only coloured on one side); brown = the pterygoid bone; blue = the bone called the vomer (wide vomers are another feature that define temnospondyls according to Schoch, 2013). Figure is modified from Reisz, Schoch & Anderson (2009). Where did they live? Temnospondyls have been found on every continent (yes, including Antarctica). Of course, they certainly didn't live in regions that are nearly inhospitable like modern-day Antarctica, although like some modern amphibians, some temnospondyls may have tolerated pretty frosty conditions. The majority however probably lived in pretty tropical environments (think Amazon rainforest). Many of the places where temnospondyls are found were at one point close to the equator and would have been somewhat warm and wet - this includes places as wide-ranging as Greenland, Texas, and South Africa, which have all drifted quite significantly over millions of years. The aquatic temnospondyls are found in lakes, rivers, ponds, and basically anywhere that gators live today (okay, maybe not golf courses). Some are even found in marine deposits, suggesting that they may have been capable of living in saltwater or brackish conditions! The terrestrial ones are a little harder to figure out because their remains usually end up in the water and aren't preserved where they actually lived. Suffice to say they probably didn't climb trees though. When were temnospondyls alive? Temnospondyls were around for a loooooong time. The oldest one shows up in Scotland (perhaps not what you expected) over 330 million years ago (the Carboniferous), and the youngest one makes it all the way to 120 million years ago (the Cretaceous) in Scotland. That's over 200 million years!!! Why'd they go extinct? We can't be sure why temnospondyls went extinct because there are so many factors that we can't observe or directly test, not to mention biases and gaps in the fossil record that can confound our interpretations. But there are two reasonable and mainstream ideas: climate change and amniotes. Most temnospondyls were probably similar to modern amphibians in depending on water to reproduce (and possibly to breathe), more so than reptiles or mammals. A lot of modern amphibians are found in humid areas, and a lot of these areas are pretty warm. When it gets cooler and drier, that tends not to work out so well, which is why there are not too many amphibians in extreme climate regions like deserts or the poles. As the continents shifted over millions of years, it tended to get drier and more seasonal in many places, which may not have worked out very well for the temnospondyls. The other factor are amniotes, which include reptiles and mammals. These animals have reduced dependency on water, particularly for reproduction, because of their amnion. Compared to modern amphibians, which lay squishy eggs in water, the shelled eggs or internal gestation of amniotes free them from having to be around large bodies of water. This gives amniotes an advantage in drier environments. The other caveat is that amniotes started getting bigger than temnospondyls over time, outcompeting or outright eating them on land. Eventually, temnospondyls ended up being mostly relegated to the water, until the spread of aquatic amniotes (especially crocodiles) finally did them in. Their last stand in Australia is associated with the continent having a fairly polar climate that would not have been conducive to croc habitation. Up next week: Names, taxonomic confusion, & temno phylogenetics 101 Refs:

Adam Yates

1/6/2019 11:59:51 pm

Hey a blog about temnospondyls! - love it. I look forward to the next installment,

Andy

1/7/2019 12:33:00 pm

A blog for Temnospondyls! Awesome! I recently started reading about prehistoric life. It started with the recently released Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs which lead me to other books covering life before the Dinosaurs including Dawn of the Dinosaurs: Life in the Triassic. Among a few others Temnospondyls really struck me as fascinating creatures. A big part of it may have been Douglas Hendersons artwork titled Congress of Metoposaurs. And now from this blog I can corrctly pronounce the last syllable of Temnospondyls.

Bryan Gee

1/10/2019 01:02:56 pm

Hey Andy, Christian Kammerer cleared this up for me (I was unsure as well) in this week's blog post ('sieve' + 'tooth')!

David Marjanović

1/10/2019 10:57:31 am

"Dendrerpeton acadianum"

Bryan Gee

1/10/2019 01:18:11 pm

Hi David, thanks for the comments. I left the Dendrerpeton figure labeled as it was originally by Holmes et al. I'm reading over your latest publication right now - understandably it's taking some time - congratulations on it finally being out!

Tony Turner

1/31/2019 02:50:10 pm

Congrats on the blog! Can't wait to see what more you have in store!

Aaron

2/8/2019 08:14:39 am

I glad to see this blog...I have been a fan of Temnospondyls (and other "giant amphibians") since I was a kid and renewed my interest when I found out about the Jurassic and Cretaceous survivors from this underestimated group. I want to see them get highlighted and not just be in the background! Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed