|

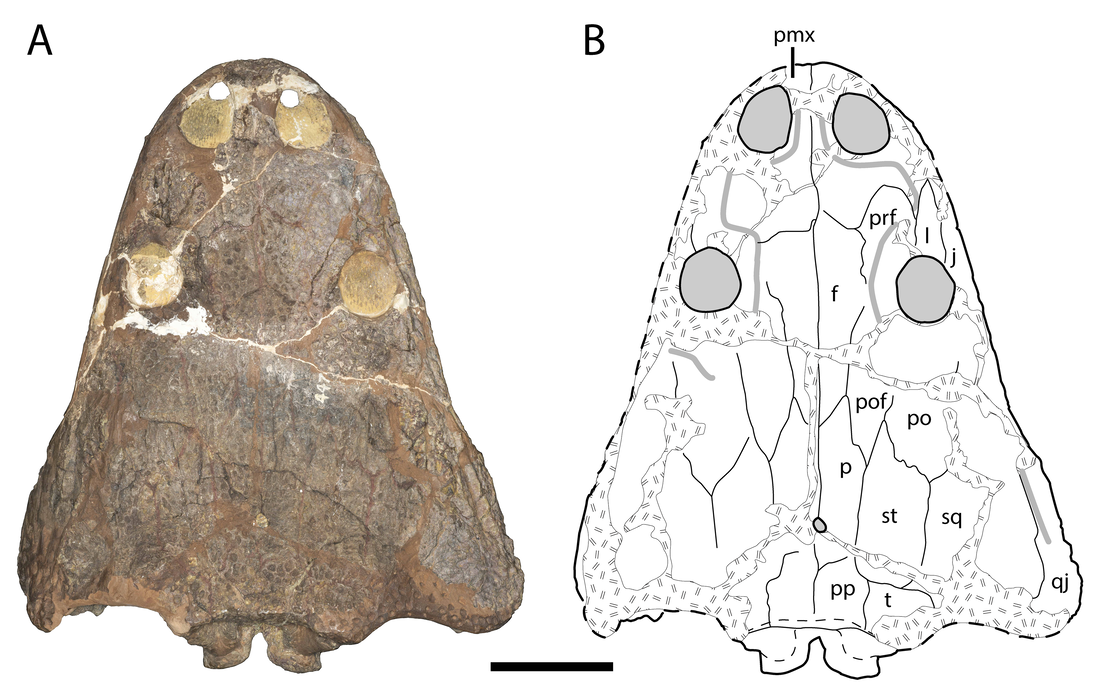

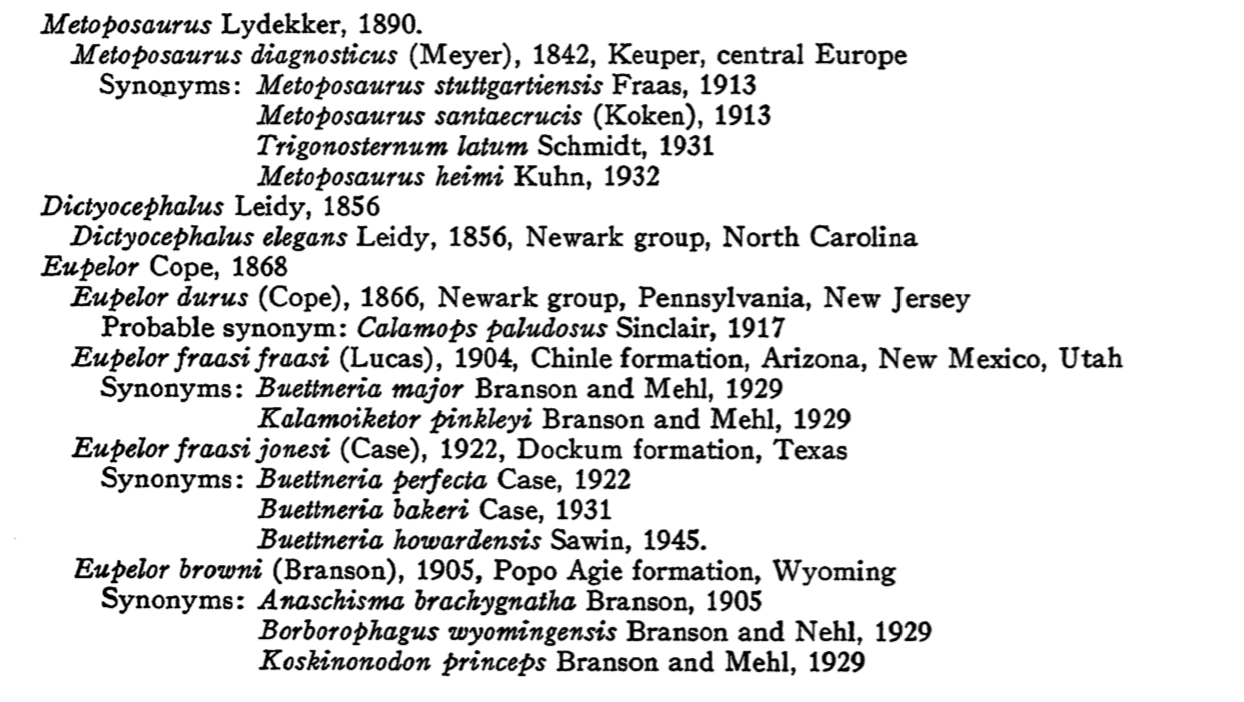

Title: Redescription of Anaschisma (Temnospondyli: Metoposauridae) from the Late Triassic of Wyoming and the phylogeny of the Metoposauridae Authors: B.M. Gee, W.G. Parker, A.D. Marsh Journal: Journal of Systematic Palaeontology Link to paper - sorry, not open access...email / DM me if you want a copy of the PDF! Summary for non-scientists Metoposaurids are my favourite clade of temnospondyls and lived in freshwater environments throughout the Late Triassic, primarily in what was the northern hemisphere then (and still mostly the northern hemisphere now): North America, western Europe, northern Africa, India, and Madagascar. They are extremely abundant fossils such that some metoposaurids are represented by dozens of complete skulls. Much of what we know comes from what we term as 'mass death assemblages' that preserve a large number of individuals. The classic interpretation of the formation of these deposits was a catastrophic drying up of a pond in which metoposaurids live, but other ideas (e.g., transport into a more concentrated deposit) generally hold more traction. Because we have these types of deposits, most research focuses on just those localities, even though metoposaurids can be found in many more places in reduced abundance. One of the areas that is often overlooked is the more northern parts of the US, such as Wyoming. There are a number of metoposaurids from Wyoming, but most of them are considered nomina dubia or junior synonyms of other taxa. One of these is Anaschisma, represented by two species, A. brachygnatha and A. browni. Both come from the same locality and in fact were found on top of each other in the same horizon. This led to much debate in the literature about whether one was just a juvenile of the other. The putative absence of otic notches was also a feature that some considered to indicate close affinities with the much smaller Apachesaurus (which I blogged about a few weeks back). In this study, we re-examined the holotypes of the two Anaschisma species and determined that (1) they are not separate species; (2) the absence of otic notches is just because one of the framing elements is damaged; and (3) that the Wyoming metoposaurids are essentially indistinguishable from the much better-known Koskinonodon perfectus, which is best known from Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. This isn't particularly surprising because the other Wyoming metoposaurids were previously synonymized with K. perfectus, but it has an important nomenclatural outcome, which is that K. perfectus (named in 1922) becomes a junior synonym of A. browni (described in 1905). This means that for the second time in the 21st century (see Mueller, 2007 for the previous time), the proper name of the most extensively studied North American metoposaurid is changed once again. The Wyoming metoposaurids may be some of the oldest metoposaurids, possibly indicating that A. browni was a relatively long-lived and successful taxon. We also include a lot of discussion points about broader systematic and evolutionary patterns among metoposaurids (e.g., are there too many genera right now). FAQWhat's the premise? Way back in 2016 when I was cooking up my first pair of publications on metoposaurids from Petrified Forest with Bill Parker, we wondered how this poorly known metopo from the Late Triassic of Wyoming, Anaschisma, fit into everything. So lest you think that I turn all of my projects into papers in <1 year, this is not one of them! We got a hand from Mike Eklund, who does all kinds of fancy photography, who went to the Field Museum and got some photographs for us (I also visited separately and checked these out while I was supposed to be doing PhD stuff). One of the main problems with a lot of these historic specimens (Anaschisma was named in 1905) is that they did a lot of "cosmetic" reconstruction with plaster, putty, etc. to fill in gaps and oftentimes, entirely reconstruct portions based entirely on their idea of what it should look like. They would even paint and texture it to look like the actual preserved fossil, so it can be pretty hard to tell what's real and what's not. A brief chronology Like most other metoposaurids, Anaschisma has really bounced around quite a lot taxonomically, being synonymized, split back out, repeat many times. A brief history is as follows:

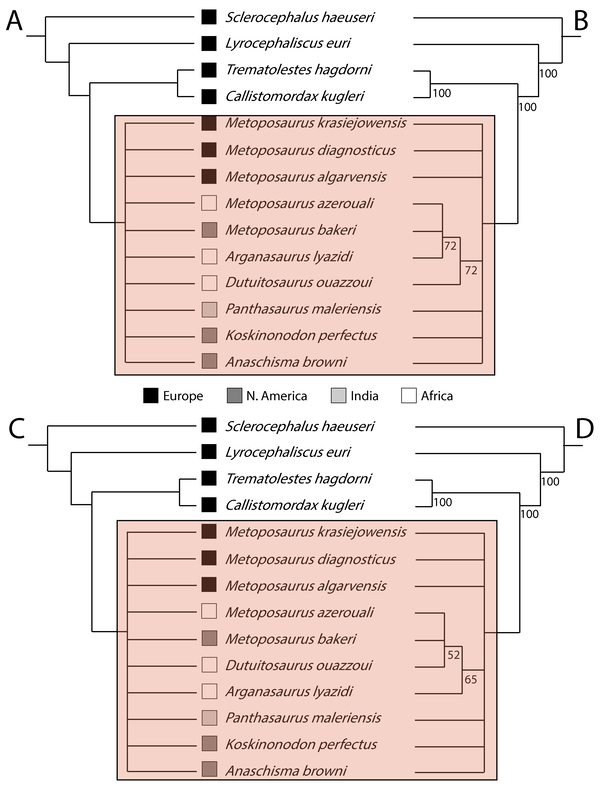

So what did you do here? The classic bread-and-butter anatomical approach of paleontology. Redescribed and figured both Anaschisma browni and A. brachygnatha (note: both are pretty reconstructed). Ran a phylogeny. Attempted to diagnose them.

What do we get out of this exercise? It's really hard to differentiate North American and European metoposaurids in particular, which is a point that I discuss in the paper as well. Might they really belong to the same genus...? Hmmm... At least the Moroccan ones came out as a cluster; they're probably the easiest ones to differentiate from the whole pack. The other thing we got out of this, which I did not see coming, was that Anaschisma and Koskinonodon, the latter being much better-known from Arizona and New Mexico, cannot be distinguished. Maybe the nostrils are a little bigger in Anaschisma? Not enough to warrant taxonomic separation if you ask us. So we synonymized them! Koskinonodon has been used more often, but this little rule of "which came first" says that the first name is the one with precedent, so Anaschisma (1905), which pre-dates Koskinonodon (1929), is the winner of this synonymy. 101 problems with metoposaurid taxonomy It's not secret that metoposaurid systematics are extremely unstable. With this latest paper, the best-known North American metoposaurid has now switched names twice in the 21st century, going from Buettneria (the original designation from 1922) to Koskinonodon (2007) to Anaschisma. This is emblematic of broader splitting and lumping (and repeat a million times) of the clade, which exceeded 20 genera at some point and is now down to just six. The practice of ascribing essentially any perceptible difference to taxonomy (i.e. at least warranting a new species) isn't exclusive to metoposaurids, but it's made very apparent because of how similar they all are to each other compared to equally ranked clades (family-level) of other temnospondyls or tetrapods. The taxonomic studies and acts accompanying the various changes to metoposaurids are emblematic of the inherent subjectivity in paleontological taxonomy. With modern species, we have many more avenues through which to evaluate whether two populations of animals are two species or just geographically separated populations of the same species. Put them together and see what happens, to name one example. Of course, in the fossil record, we don't have this option (amongst other things like molecular or soft tissue data). As a result, there is often a tendency to associate extinct tetrapods with the geographic ranges in which they occur and to use this to determine species differentiation. Of course, this underestimates their true geographic range because of gaps in the fossil record; if rocks from a certain time period are not preserved, then animals from that time period that did live there can't be preserved there. For example, in North America, our best records of metoposaurids are from the southwest, but they also occur along the eastern seaboard and then into northern Africa and western Europe. Simply because we don't find them in the middle of the U.S. doesn't mean that they didn't live there - we just don't have records from that time period out that way. Metoposaurid classification has long been plagued by these ideas that they must be stratigraphically, geographically, temporally, etc. restricted. A good example of this is Colbert & Imbrie's (1956) classification scheme (below); they really bought into this subspecies idea (very rarely used in vertebrate paleontology) and used it to split taxa by which geologic formation they occur in. Like I said above, they all look basically the same, so are there actually this many genera or species...? More on that in the future. Main conclusions?

Do you ever actually work on your dissertation? On occasion. Refs

David Marjanović

5/31/2019 03:30:59 pm

Yay! I haven't actually read it yet, but this looks like great, overdue work that will be very useful! Does it form part of your dissertation? (Mine consists of the papers I published up to 2010, plus introductions, a common introduction, and statements which parts I did and which are due to my coauthors.)

Bryan Gee

6/3/2019 08:55:53 pm

Ah thanks for pointing that out David! An expert on the little details as always. Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed