|

Title: New publication (First record of the amphibamiform Micropholis stowi from the lower Fremouw Formation (Lower Triassic) of Antarctica Authors: B.M. Gee, C.A. Sidor Journal: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2021.1904251 General summary: Following the end-Permian mass extinction (252 mya), life on Earth hit a big reset button. Many major groups suffered substantial losses in biodiversity or went entirely extinct, being replaced by other groups that were rare or non-existent before the extinction. The temnospondyl amphibians are no exception - almost all of the characteristic groups found in the Permian are entirely wiped out, and that ones that survive it are found in very low diversity and are restricted to mostly a few localities that would have been at high latitude. Concurrent with this is the observation that a lot of the first temnospondyls that appear in the Early Triassic are rather small compared to their Permian predecessors or their later Triassic successors. One of these is a holdover from the Permian, the amphibamiform dissorophoids. There is only one definitive amphibamiform in the Triassic (there were over 30 in the Permian), Micropholis stowi, a species known from South Africa for over 150 years now. Our study reports the first record of M. stowi from outside of South Africa, in similarly aged Early Triassic rocks from Antarctica. This further solidifies the similarities between the Early Triassic of Antarctica and South Africa, but it still comes in the face of somewhat stark endemism otherwise - most of the temnospondyls known from the southern hemisphere at the time are found in only one spot, despite there being a rich record of this group in places like South Africa, Australia, India, and Madagascar. This is also the first paper from my postdoc and sets the stage for some of our in prep projects on other newly collected material from Antarctica!

Title: Description of the metoposaurid Anaschisma browni from the New Oxford Formation of Pennsylvania Authors: B.M. Gee, S.E. Jasinski Journal: Journal of Paleontology DOI: 10.1017/jpa.2021.30 The amazing art above was done by Sergey Krasovskiy; you can find his DeviantArt profile here and his Twitter here! The number of metoposaurids is not random - we know that there were at least two individuals preserved at the site based on the number of duplicate elements from the site. General summary: This study provides the first detailed description of metoposaurid temnospondyls from Late Triassic deposits in Pennsylvania. Metoposaurids are well-known for their widespread distribution in the Late Triassic, including in the southwestern U.S., but they have a much scarcer record west of Texas. The east coast in particular was geographically closer to other regions that preserve metoposaurids that have drifted apart over the millenia, like northern Africa and western Europe. The east coast is also the only region in North America where a large-bodied temnospondyl that isn't a metoposaurid is known from (this pattern of metoposaurid exclusivity is not observed anywhere else with decent sampling). While previous people have mentioned the Pennsylvania material and ID'd it, they never provided good figures or explicit justification for their ID, so essentially any reader was left to take them at their word. We formally describe the material, identifying it to Anaschisma browni (best known from Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Wyoming), which is not the same species that a metoposaurid from Nova Scotia belongs to, and discuss the importance of providing proper documentation and justification for taxonomic identifications (which are fluid hypotheses, not static facts). While the east coast is much more fossil-poor (this is definitely the best metoposaurid material from anywhere in North America west of Texas), it may also be the only region that preserves the transition from a diverse large-bodied temnospondyl assemblage to one that is entirely dominated by metoposaurids.

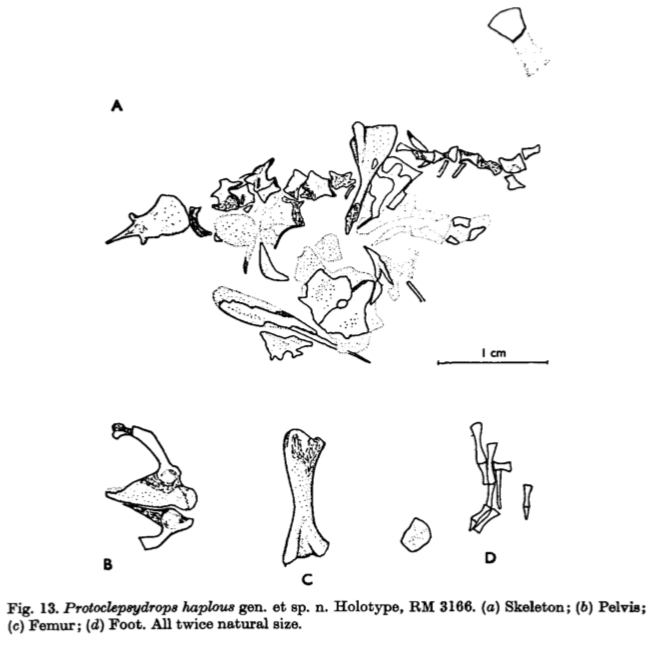

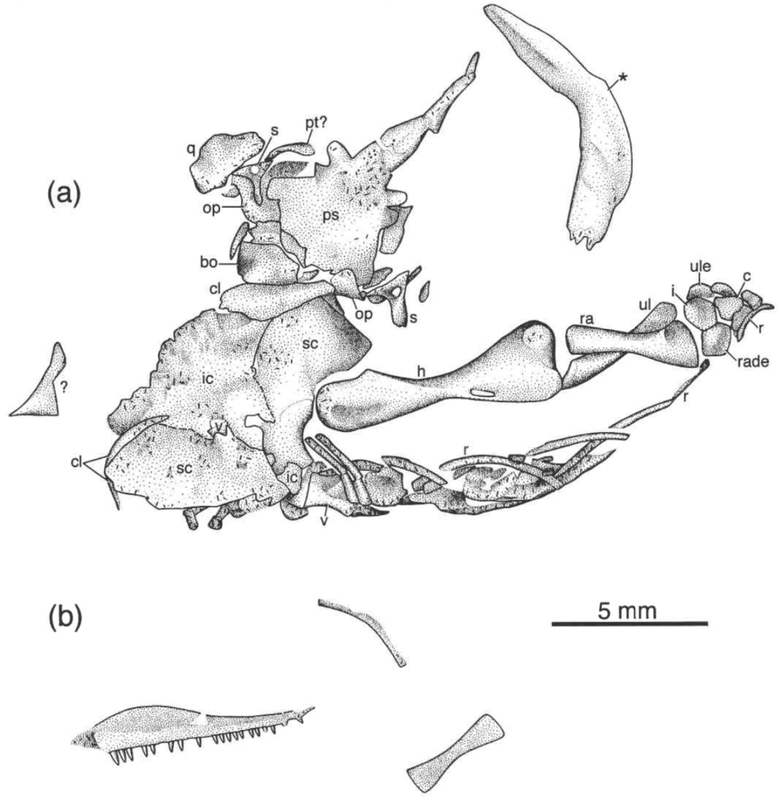

Title: New information on the dissorophid Conjunctio (Temnospondyli) based on a specimen from the Cutler Formation of Colorado, U.S.A. Authors: B.M. Gee, D. S Berman, A. C. Henrici, J.D. Pardo, A. K. Huttenlocker Journal: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2020.1877152

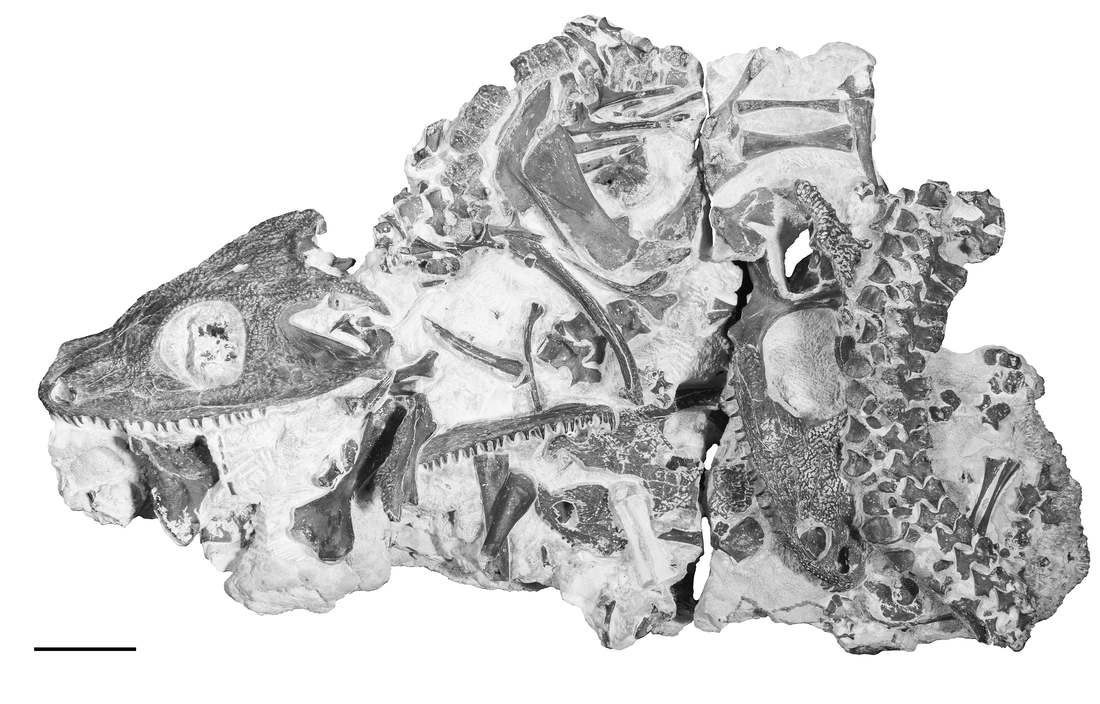

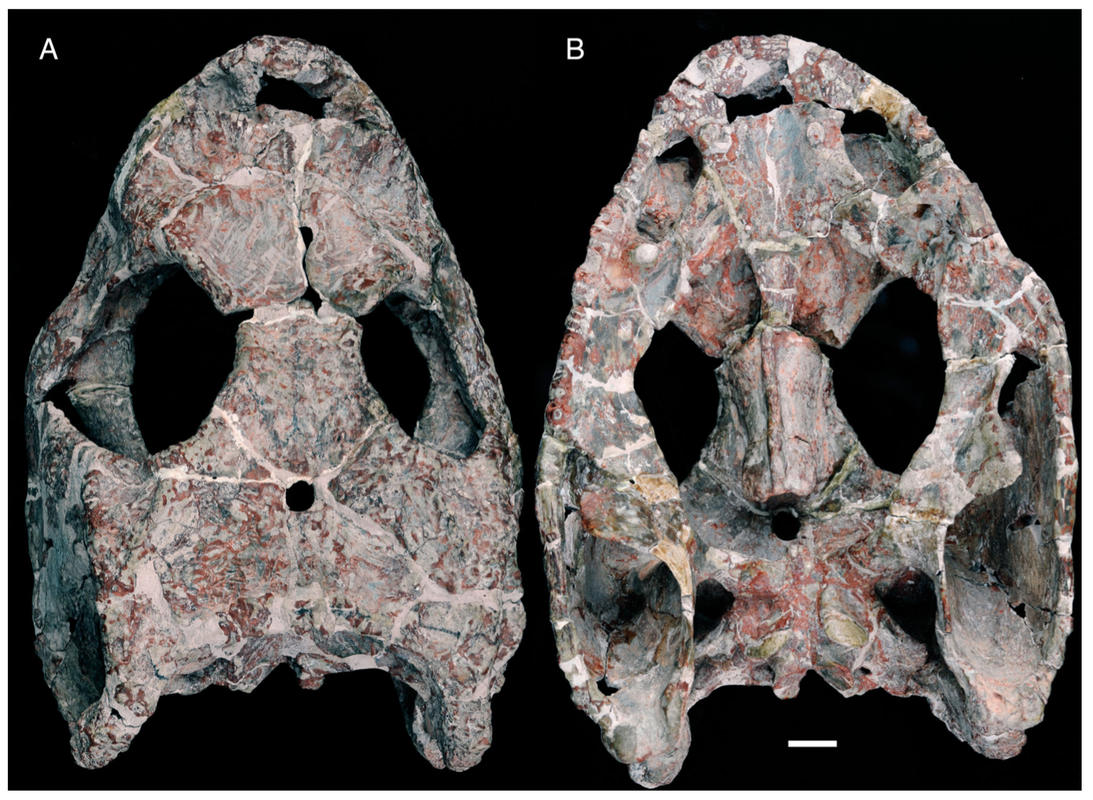

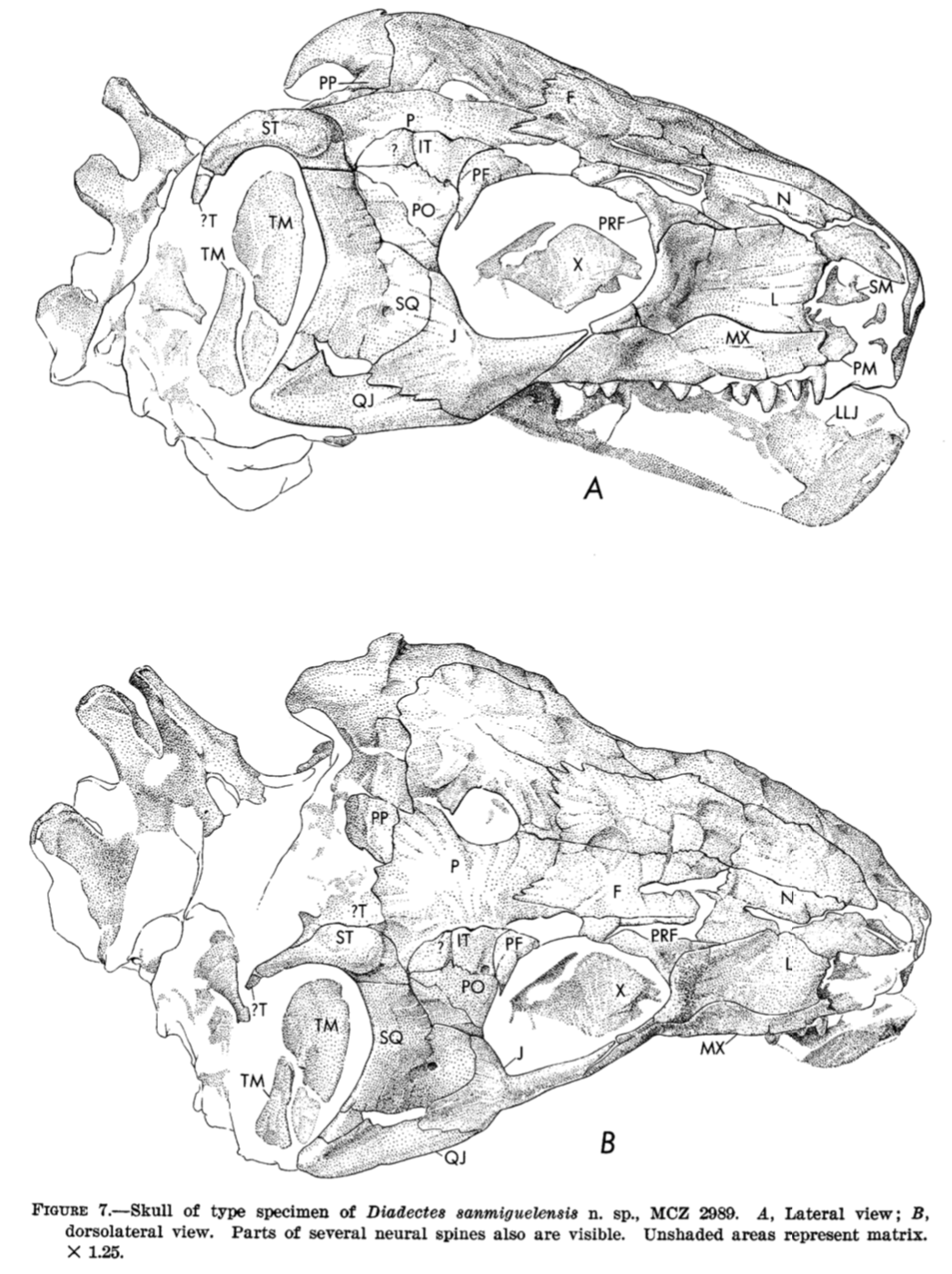

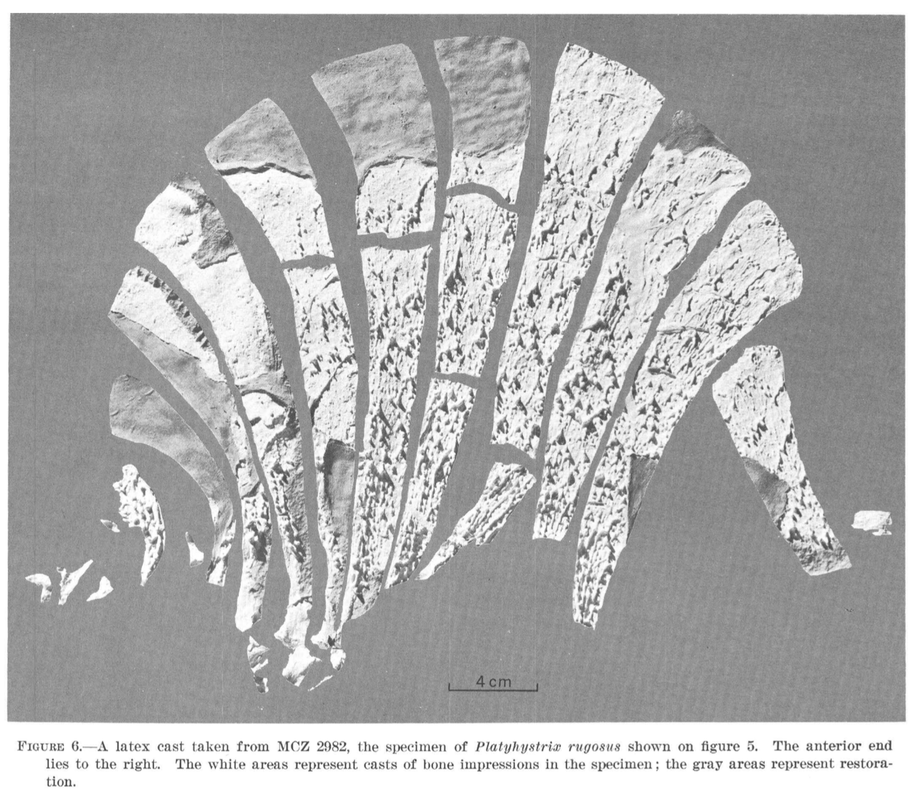

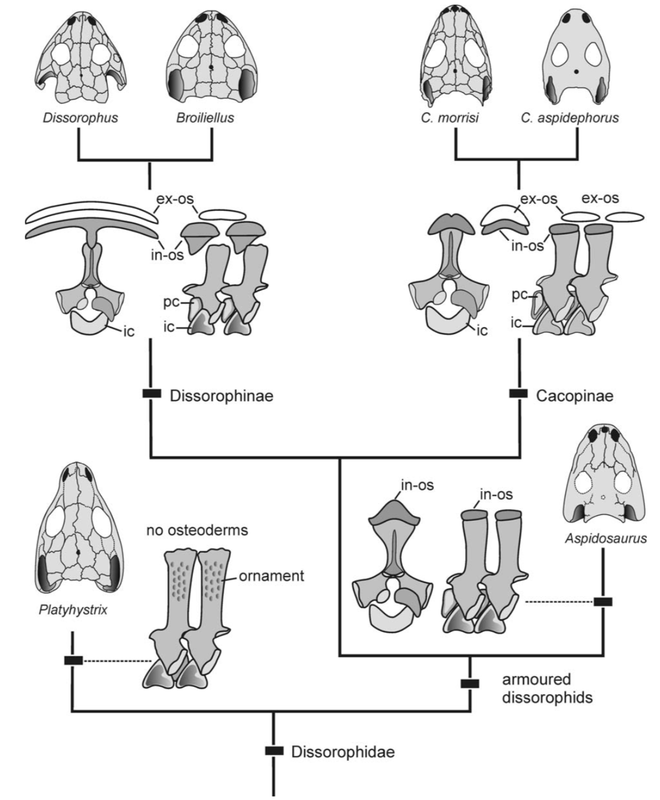

The Red RiverThe Red River is a mostly east-west oriented, eastward-flowing indirect tributary of the Mississippi River, stretching from the Texas Panhandle all the way to Louisiana (over 1,350 miles). It forms the border between Texas and Oklahoma (hence where the "Red River Rivalry" in collegiate football between University of Texas and the University of Oklahoma derives from), two of the most historically productive states for early Permian tetrapod fossils (especially the famed Texas redbeds). Much of our record of North American temnospondyls from this time comes from these two states, with more minor contributions from New Mexico, Utah, and Ohio. Dissorophids, the armoured dissorophoids, are among the best known taxa from these redbed deposits, and in many instances, the entire record of a given species is restricted to one or two states. Whether this is an artifact of the fossil record or an accurate representation of a truly restricted geographic range is often unclear; many taxa are in fact known from only one specimen or one site (the two species of Cacops below are examples; figures from Gee & Reisz, 2018 and Anderson et al., 2020). Land of Enchantment Conjunctio multidens (reconstruction from Schoch & Sues, 2013) is one such dissorophid, known only from two sites (but the same county) in New Mexico. Although New Mexico and Texas are adjacent states, their faunal assemblages were somewhat different, a result of regional geography no longer present that would have created some degree of spatial segregation. Other examples can be found in the trematopids Anconastes and Ecolsonia, only found in New Mexico, or the dissorophid Broiliellus reiszi, which differs starkly from other members of the genus that are known from Texas. Because the Texas redbeds have been so extensively sampled, with at least a dozen other dissorophids known, it can be reasoned that indeed Conjunctio also did not occur in Texas. But does that mean that it was only found in New Mexico? Not necessarily. The rest of the Four Corners region and the midcontinent is less well-explored, probably because the early Permian deposits that yield tetrapod fossils are less extensive. One of the well-known productive localities in the Four Corners region is in the Placerville area in Colorado, where the Cutler Formation (also found in New Mexico) is several hundred meters thick. First reported by Lewis & Vaughn (1965), the assemblage preserves one of the few sails of the dissorophid Platyhystrix (below on right), the holotype of Diadectes sanmiguelensis, a diadectomorph stem amniote (below on left), and a number of other tetrapods also known from other redbeds deposits. Synapsid fans may also know this as the type locality for the sphenacodontid Cutleria.

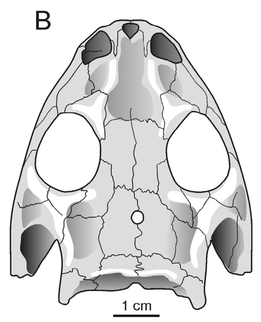

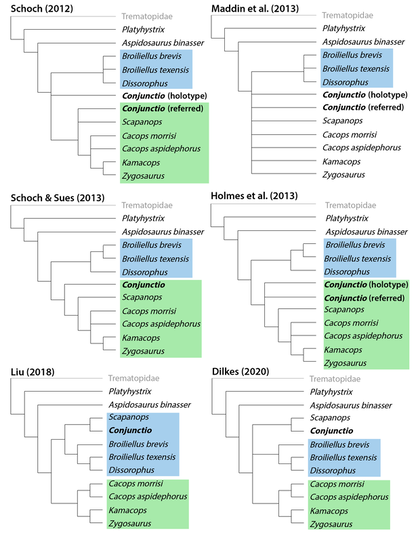

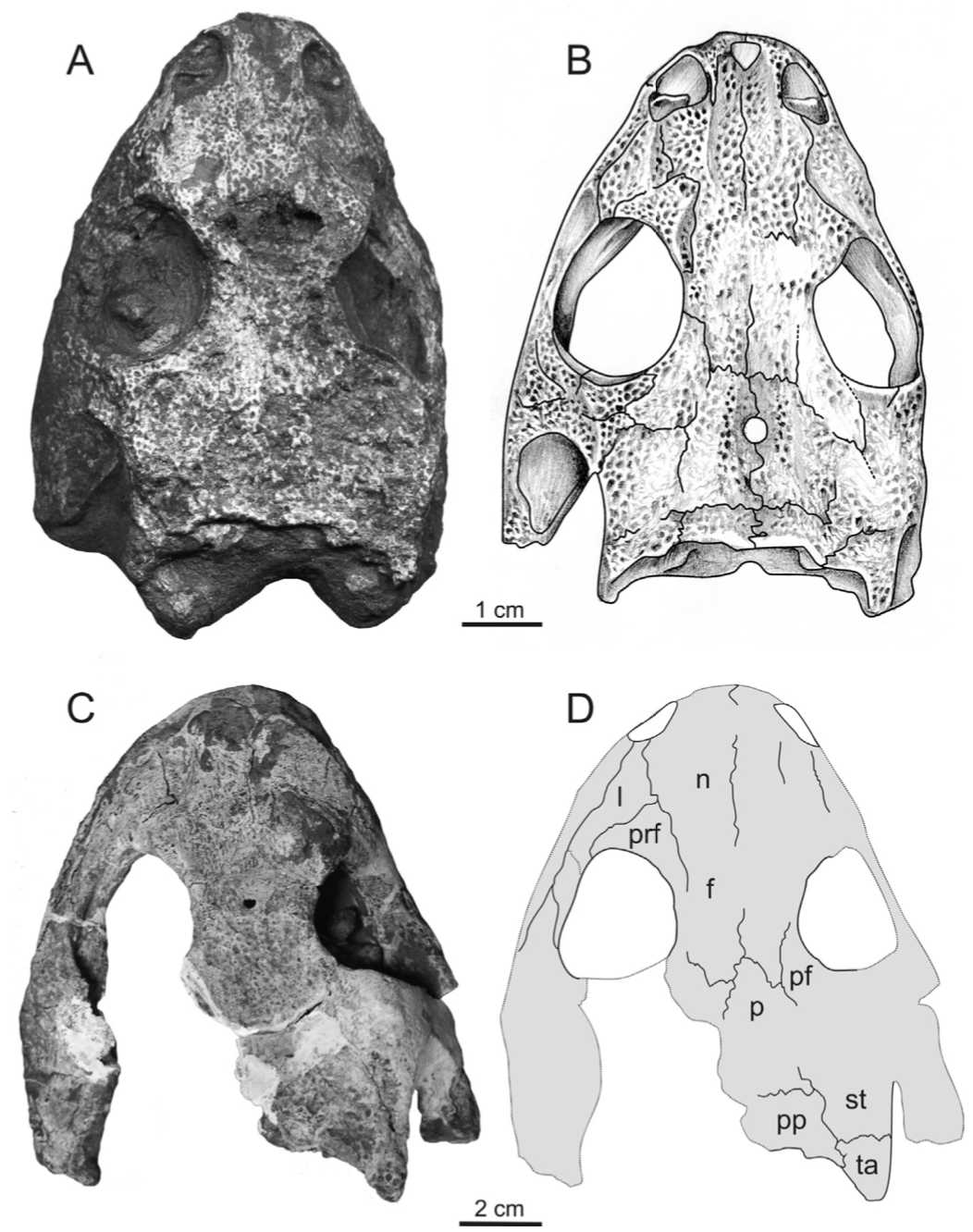

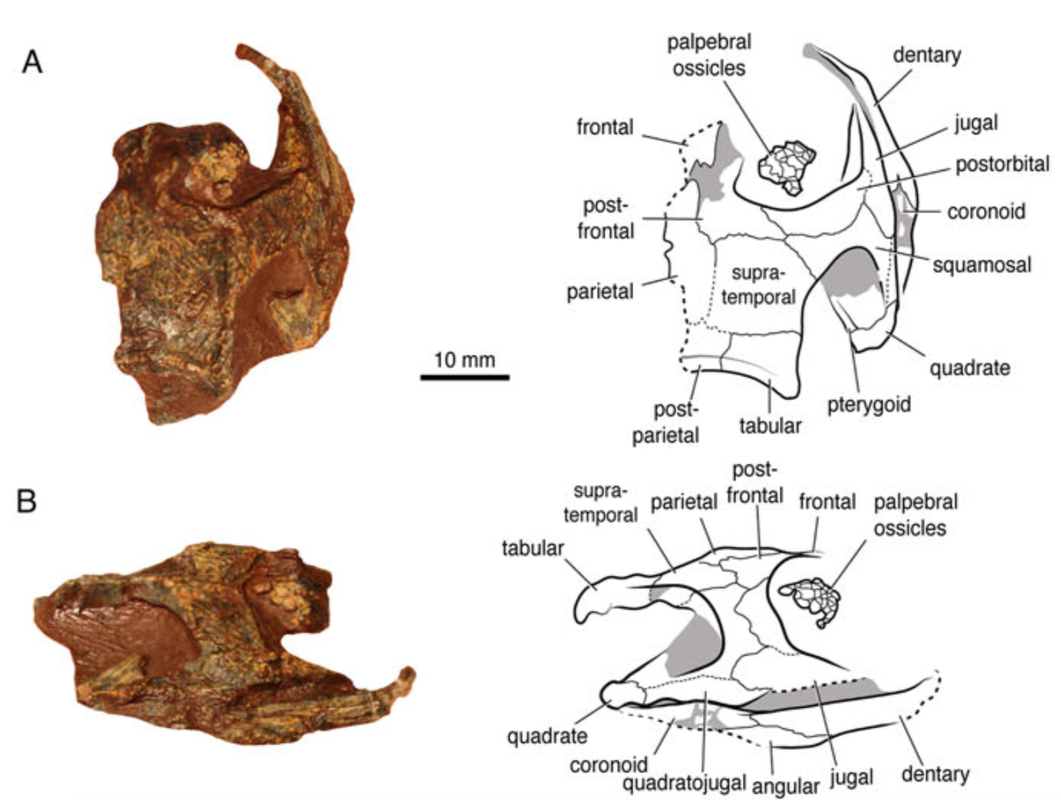

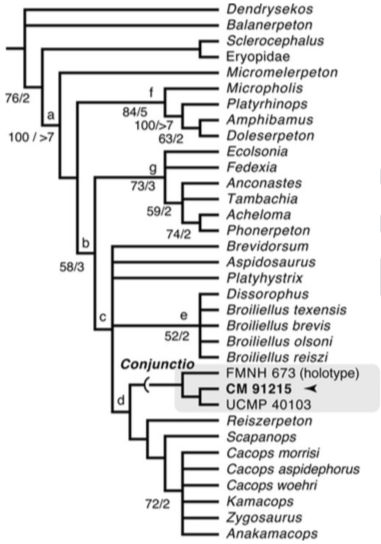

Terminology: While 'transitional form' or 'transitional fossil' is a commonly used term that even the general public knows (e.g., Archaeopteryx), scientists are moving away from it because it's misleading, suggesting that one animal directly turns into another (one of the most common misconceptions about evolution). In fact, this very rarely occurs (a process called anagenesis), and it does not capture major transitions like the theropod-bird transition or the fish-tetrapod transition. Instead, continual splitting of new species that go extinct is what gradually leads to a shift in a group's anatomy. A given species' suite of features may be transitional insofar as it captures part of this shift, but the species or individual itself is not. Agree to disagree Comparison of different phylogenetic results with Conjunctio. Boxes refer to dissorophid subfamilies: green = cacopines, blue = dissorophines. Comparison of different phylogenetic results with Conjunctio. Boxes refer to dissorophid subfamilies: green = cacopines, blue = dissorophines. As one might expect from a taxon with a weird mixture of features, there is no agreement on the position of Conjunctio in phylogenetic analyses of dissorophids, as summarized on the right. Historically, the phylogeny did not support that they were conspecific (expected recovery as exclusive sister taxa), as they were frequently scored separately due to uncertainty over Carroll's referral (the referred specimen was called the "Rio Arriba Taxon"). It doesn't really help that the holotype (C-D) and the much smaller referred specimen (A-B) differ from each other in cranial proportions, somewhat questioning whether they are actually the same taxon (since Bob Carroll created Conjunctio in 1964). You don't have to be a paleontologist to look at the two specimens above and kinda wonder whether they are actually the same (or whether the bottom one can be said to be much of anything really). Sometimes both specimens were recovered as eucacopines (Holmes et al., 2013), sometimes only one was recovered as a eucacopine (Schoch, 2012), sometimes Eucacopinae didn't exist (Maddin et al., 2013), sometimes the composite was recovered as a eucacopine (Schoch & Sues, 2013), and sometimes the composite was recovered as a dissorophine (Liu, 2018). So basically every possible result short of it being recovered as a non-dissorophid! The Centennial StateThe new specimen that we report here was collected from what's known as the Placerville locality by my coauthors, Adam Huttenlocker and Jason Pardo, a few years back. It is not nearly as complete as the other two specimens, but it is well-preserved, enough to show some distinctive features not found in most or all of the other dissorophids. For example, the two bones called the postorbital (right behind the eye) and the supratemporal (a little farther back) usually touch, but here they do not (this is found in two of the species of Cacops as well). The jaw articulation (marked by the quadrate) also sits in front of the level of the back of the skull (marked by the postparietal); this is something found only in Dissorophus and Scapanops. So there is actually quite a lot of information in this little skull despite it being at best 25% complete! Our phylogenetic analysis, which combines two previous matrices (it was originally intended for a larger sample), finally recovers not just the original two specimens, but also this third one as a proper clade (i.e. what you expect if they really do all belong to the same species)! The statistical support is not very good though, and it's quite possible that a future study could find a different result. Dissorophid phylogenetics remains very much in flux outside of just Conjunctio (something that I'm working on right now). COVID addendum: Lest someone think that all of us are superhumans who pumped out this paper in the pandemic, it was mostly completed before the pandemic really set in (we submitted the first version in May 2020). Jason and I in particular as current and recently graduated PhD students have really slowed down in putting new work into the pipeline during the pandemic, which I think is important to note since a lot of people are really struggling and should not be concerned with their perceived relative productivity! Refs

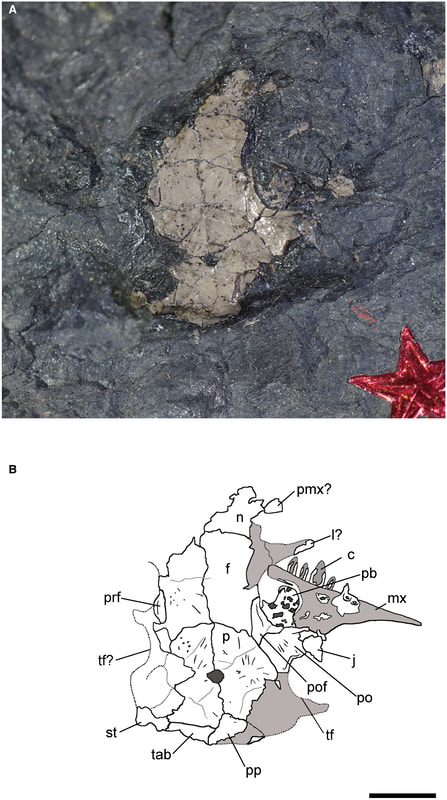

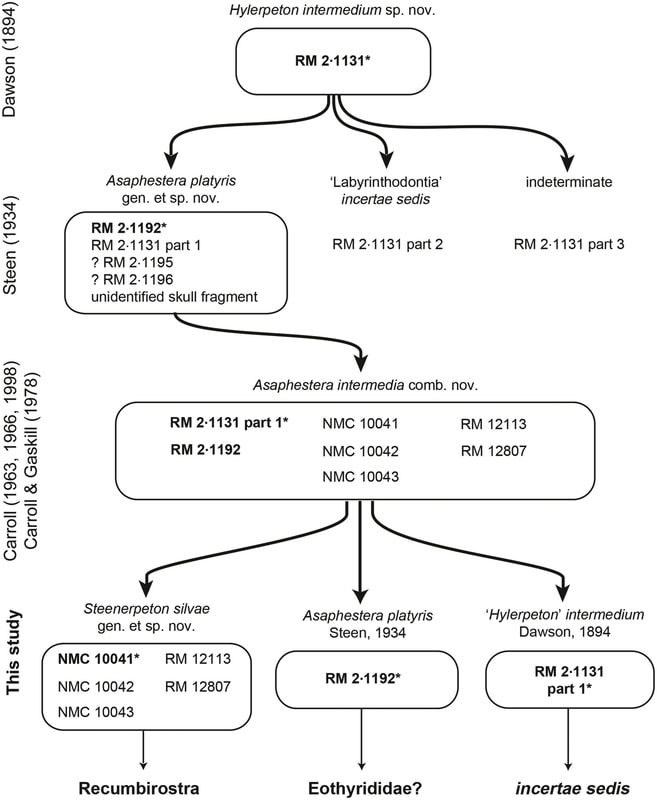

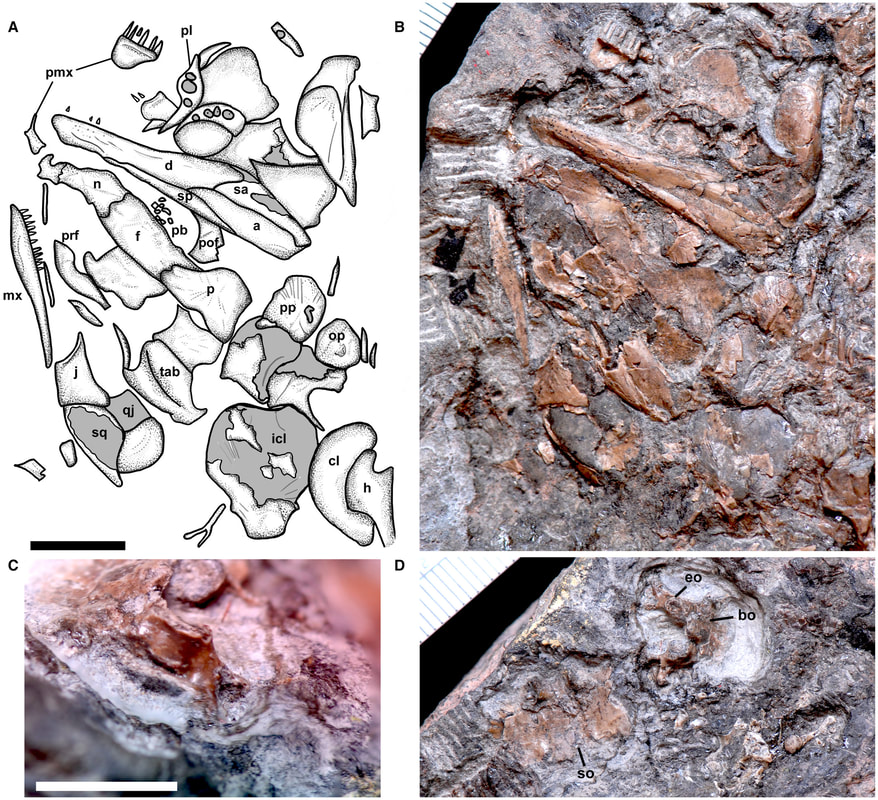

Title: Reassessment of historic ‘microsaurs’ from Joggins, Nova Scotia, reveals hidden diversity in the earliest amniote ecosystem Authors: A. Mann; B.M. Gee, J.D. Pardo, D. Marjanović, G.R. Adams, A.S. Calthorpe, H.C. Maddin, J.S. Anderson Journal: Papers in Palaeontology DOI to paper: 10.1002/spp2.1316 General summary: In what is my biggest collaboration to date with nearly all of the early tetrapod workers in Canada, here's probably my last paper of 2020: a very thorough revision of the 'microsaur' Asaphestera from Joggins, Nova Scotia! Joggins is one of the oldest sites with a well-preserved late Carboniferous tetrapod community (315-318 Ma), and it preserves a unique forest swamp environment in which animals are frequently preserved inside of logs (whether or not they lived in the logs is another question). Because of its age, Joggins is critical for exploring the early origins of many groups, as it often preserves the oldest members of many Paleozoic clades in North America, if not globally. For example, the temnospondyl Dendrerpeton from Joggins is the oldest known temnospondyl on the continent. There's a rich suite of 'microsaurs,' the ever controversial group of tetrapods of unclear affinities to either crown reptiles or to crown amphibians, that have been reported from Joggins, but many of the original studies are dated such that the interpretations are of limited utility for modern workers trying to elucidate phylogenetic relationships and other macroevolutionary trends. The frequent disarticulation and fragmentation of specimens also makes referrals of specimens to the same taxon somewhat suspect, with the potential for purportedly well-known taxa to be represented by a chimeric blend of multiple taxa. We spent a lot of time looking at historic specimens of one such 'microsaur,' Asaphestera, because we were particularly interested in exploring some of these very poorly known Carboniferous 'microsaurs' that are really important for understanding the evolution and relationships of the much better known early Permian taxa that everybody on this paper has studied to various degrees. Through this, we identified that the various specimens lumped under Asaphestera intermedia are actually a hodge-podge of different taxa, at least one of which is not even a 'microsaur,' but as we propose, is perhaps the earliest definitive synapsid! The oldest synapsid?

Microsaur math

RM 2-1131 was the original holotype of Hylerpeton intermedium and became the holotype of the new Asaphestera intermedia. Here it is above on the right. If the figure does not look that impressive...that's because the specimen is not very impressive. We couldn't identify it to a particular tetrapod clade, let alone diagnose it as a unique taxon of whatever clade that might be, and we designated it as a nomen dubium ("doubtful name"), which is the fancy way of saying "this is not valid because it is not clearly unique." So at this point, we've killed one 'microsaur.' Net: -1 microsaur

In any event, we then set about examining the referred specimens of "Asaphestera intermedia," at this point a sunk taxon, because some of them are much nicer. The one above was sufficiently complete to be diagnosed and differentiated from other taxa, and we made it a holotype of a new 'microsaur' taxon: Steenerpeton silvae, which we named for Margaret Steen, (the same Steen I keep mentioning throughout this post), and for 'of the forest,' referring to Joggins original paleoenvironment. So now we've added back one 'microsaur!' Net: +0 microsaurs Steenerpeton appears fairly derived already, in contrast to traditional interpretations of Asaphestera of any flavour, and we suggest that it may be a recumbirostran, the derived group of 'microsaurs' that host a suite of fossorial adaptations. This actually lines up well with the documented presence of other derived 'microsaurs' like possible pantylids and gymnarthrids at Joggins and provides more evidence that the origin and diversification of recumbirostrans begin earlier than has been historically conceived and probably occurred in an interval without substantial body fossils. The former point in particular is a real running theme at this point for most of the research that all of us do.

Avengers assemble!This is the biggest collaboration I've ever worked on (some might say the most ambitious crossover ever). It was born nearly 2.5 years ago at the SVP Annual Meeting in Calgary, which is where Arjan and I both gave talks on different 'microsaurs' (Arjan's turned into his published paper on the new Mazon Creek 'microsaur' Diabloroter, and mine turned into my published paper on new material of Llistrofus from Richards Spur). Jason Pardo (and Jason Anderson) had just had a high-profile paper come out that summer that recovered 'microsaurs' as crown amniotes, a paper I didn't stop hearing about from my advisor even though I spent the whole summer doing fieldwork in Arizona. We all ended up talking about future directions for 'microsaur' work and agreed on needing to reevaluate a lot of the earliest records of what are called "tuditanomorphs" to better characterize them for big tetrapod analyses to continue to sort out different relationships. This in turn spawned what's become a dynamic working group among the three of us and eventually led to us jokingly assigning ourselves as different members of the Avengers as this team of early career researchers doing early tetrapod work on basically every single clade that's out there. If you add up everything that we've collectively published, we account for actinopterygian and sarcopterygian fish, aïstopods (stem tetrapods), temnospondyls, parareptiles, seymouriamorphs, embolomeres, synapsids, and 'microsaurs.' You can see some of the other fruits of this working group in Pardo & Mann (2018), Mann, Pardo & Maddin (2019) and Mann & Gee (2020), with plenty of future work slated for the immediate future (or once things sort of go back to normal)! I will leave it to the readers' imagination as to which members we have self-assigned as... The final sumThe Joggins 'microsaurs' are the only taxa from Carboniferous localities that have experienced these sorts of "lump/split" boom-bust cycles, going from being remarkably taxonomically diverse to remarkably intraspecific variable and back again. The classic Joggins temnospondyl, Dendrerpeton, is another great example of this; the type species, D. acadianum, includes several defunct genera such as Smilerpeton (great name) and Dendryazousa. There are numerous taxa that have been named that weren't even assigned to the correct clade! A lot of this has been because of historic interpretations based on the often fragmentary and disarticulated specimens at Joggins; we don't get many 3-D specimens, and the distortions can affect interpretations of the anatomy. This means that there's a lot of room to go back and look at specimens that were often collected more than 120 years ago and that haven't been re-examined in detail in more than 60, 70, 80... years to assess the original interpretations. Particularly in light of new discoveries at other localities, updated taxonomy, and the recognition that a lot of clades have deeper origins than was often hypothesized in the early 20th century, exploring one of the oldest (crown) tetrapod assemblages in the world is essential for unraveling a lot of the mysteries of the origin of the modern tetrapod clades. When we started this project, there were seven 'microsaurs' recognized from Joggins: Archerpeton, Asaphestera, Hylerpeton, Leiocephalikon, Ricnodon, and Trachystegos. We added Steenerpeton (total: 8), but deep-sixed Archerpeton, recognized Asaphestera proper as a synapsid, and cast doubt on the Joggins records of Ricnodon (final count: 5). We've got plans for some of those other ones that didn't get addressed here...stay tuned for plenty more studies coming out on Joggins material and other Carboniferous faunas! Refs

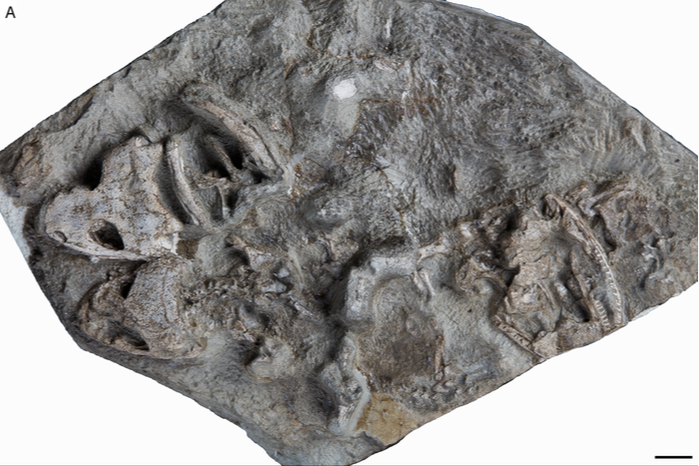

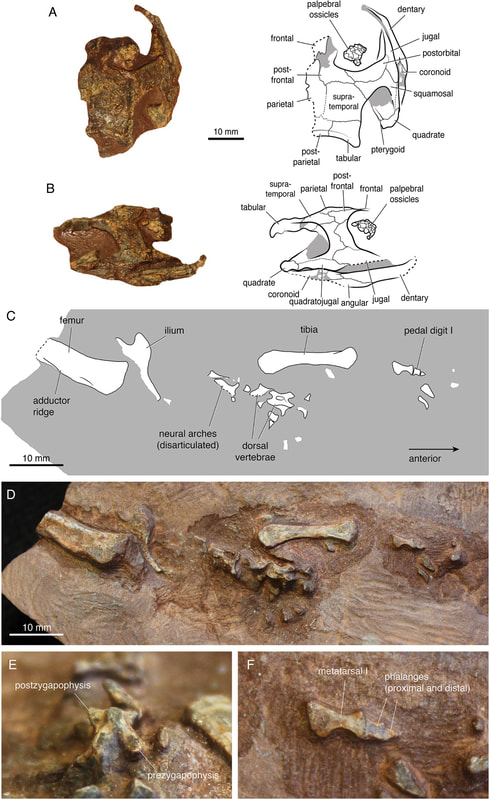

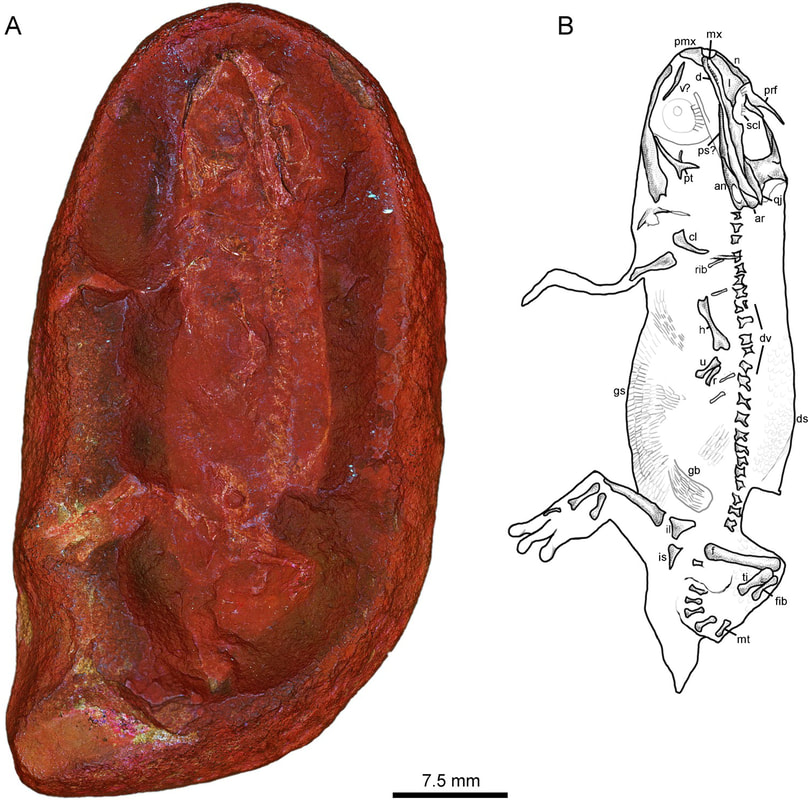

Title: Lissamphibian-like toepads in an exceptionally preserved amphibamiform from Mazon Creek Authors: A. Mann; B.M. Gee Journal: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology e1727490 DOI to paper: 10.1080/02724634.2019.1727490 Note: this paper came out on Wednesday, but it took a little while to get around to the blog post. As you can imagine, it's a little hard to write a blog in the middle of a pandemic. I actually plan to try to rev things back up in a week or two after I finish a bunch of problem sets for my stats classes, so stay tuned... General summary: Late Carboniferous Lagerstätte (fossil sites with remarkable preservation) are incredibly important for our understanding of the early evolution of many tetrapod clades. Mazon Creek in Illinois is one of the most famous Lagerstätte in North America and has produced a slew of both vertebrates and invertebrate material of great interest to paleontologists across the board (this is also where the famed Tully Monster comes from). The tetrapods have been studied by some of the most preeminent Paleozoic workers, including Moodie, Gregory, Watson, Westoll, Olson, and Baird, as well as by living paleontologists such as Jason Anderson and Andrew Milner. Preservation at Mazon Creek occurs in nodules that can be cracked in half to hopefully reveal a marvelous fossil within (or just a boring clay ball). Not only do these nodules often preserve complete, articulated skeletons, but they often preserve soft tissue structures (which is how we get a lot of records of squishy invertebrates). Here we describe a nice amphibamiform specimen (recalling that amphibamiforms are widely hypothesized to be on the lissamphibian stem) that preserves the oldest (quite possibly the only) record of toepad ('toe pad' with a space?) structures in a temnospondyl that superficially resemble those of lissamphibians. Arjan's doctoral dissertation is on Mazon Creek (the amniotes mostly); talk to him (arjanmann[at]cmail[dot]carleton[dot]ca) if you wanna know more about the exciting stuff going on!

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed