|

Fresh off a collections visit to the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, it seems only fitting to blog about what I think is one of the greatest strengths of their collection - the Paleozoic tetrapods! The Carnegie owns one of the largest collections of Paleozoic tetrapods from the American southwest (especially New Mexico) and from the more geographically proximal Dunkard Basin (Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia). Much of this was both collected and studied by emeritus curator David Berman and collections manager Amy Henrici, as well as the late Peter Vaughn, a longtime professor at UCLA who taught Dave (among many other paleontologists). Among the stash of early tetrapods are important holotypes of three trematopids, the large dissorophoids with peculiarly long nostrils that I've done some work on myself, so it seems only fitting to do a blog post highlighting a little bit more about these weird animals. Ecolsonia cutlerensis

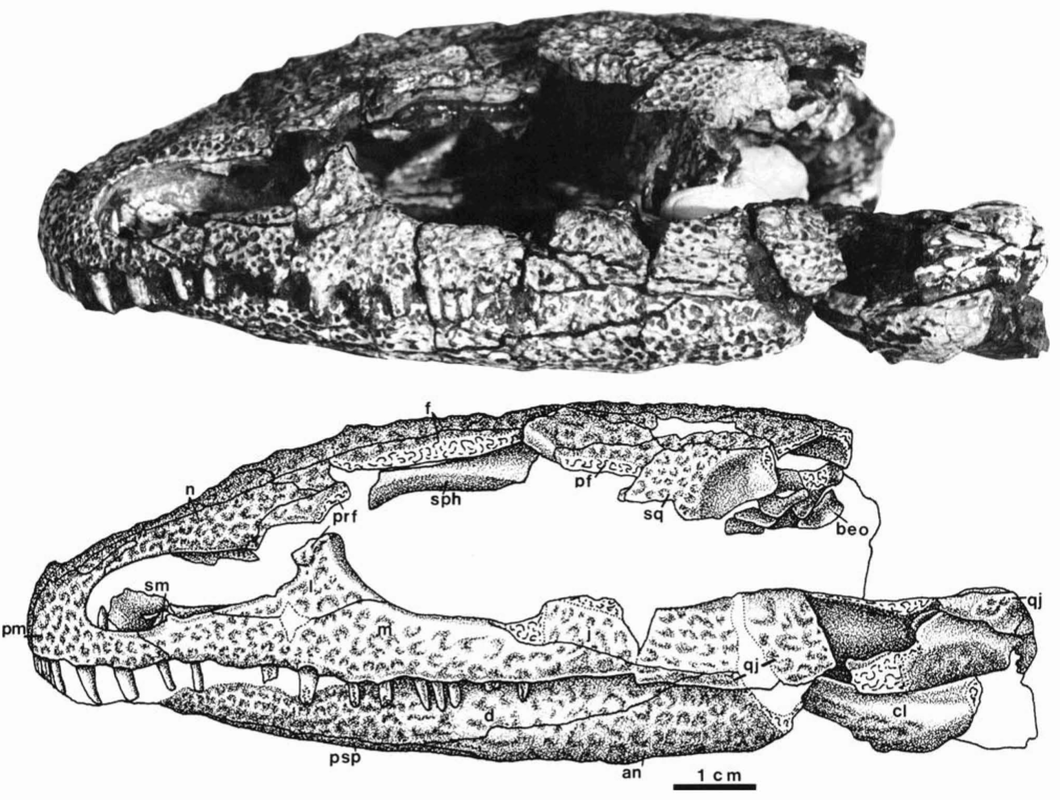

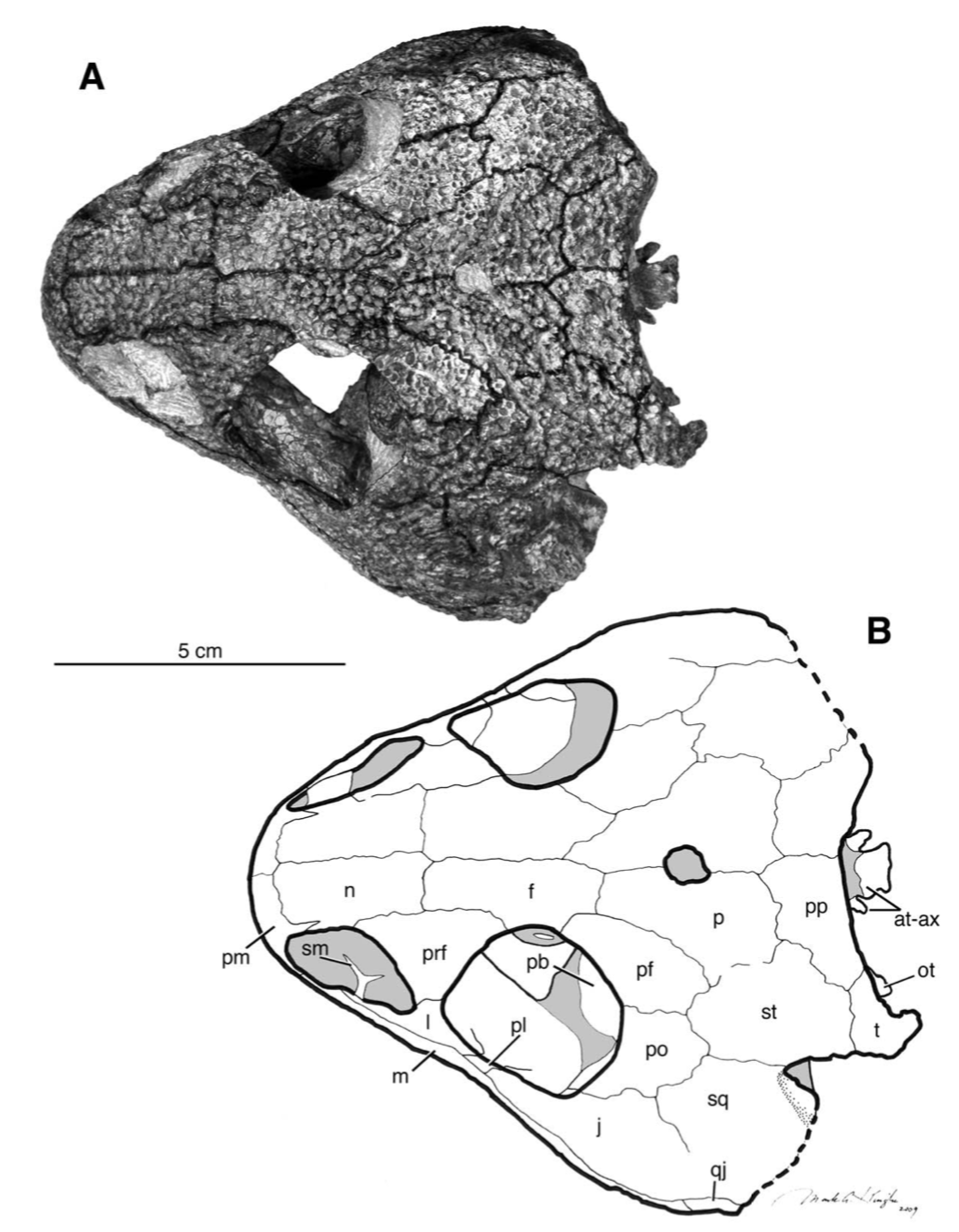

Now it's important to note that Vaughn wasn't wrong - dissorophids and trematopids are closely related - they collectively form Olsoniformes - and even though amphibamiforms are not dissorophids, they are the sister group to Olsoniformes. It's sort of like getting the right answer on one of those grade-school math problems but doing it in some weird way that your teacher didn't expect or teach you to do. But realistically, the holotype of Ecolsonia is one of the most incomplete of any trematopid (probably only that of Mattauschia laticeps is more incomplete), and it lacks most of the traditional features used to identify trematopids, such as a definitive exclusion of the palatine from the interpterygoid vacuities or a medial inflection of the prearticular. The nostril is long, but it also seems that long nostrils show up several times outside of trematopids (see Nanobamus, for example).

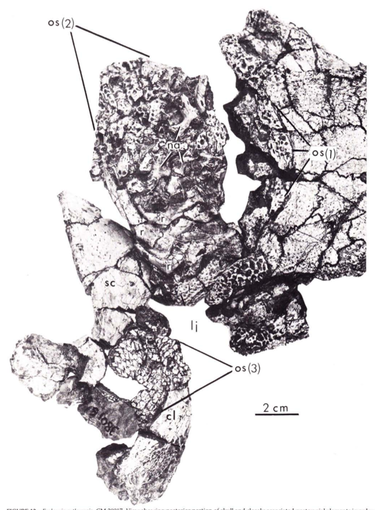

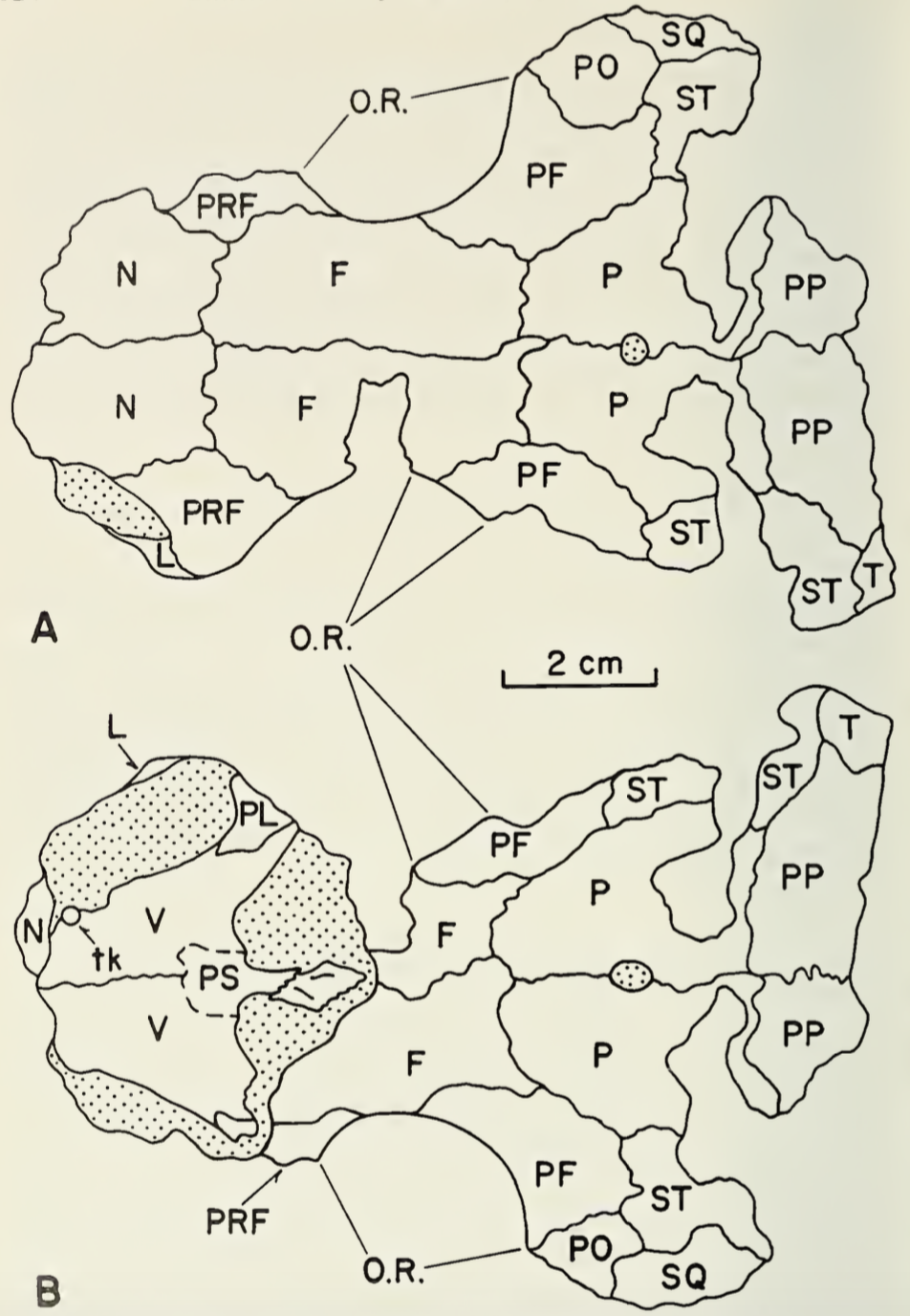

Articulated postcrania from the anterior trunk region of a specimen of Ecolsonia. 'os' refers to osteoderms, and the numbers refer to the different types. os(1) are the osteoderms covering the neck region; os(2) are the osteoderms covering the top of the trunk; and os (3) are the osteoderms covering the underside of the trunk (which may be scales; figure from Berman et al., 1985). Articulated postcrania from the anterior trunk region of a specimen of Ecolsonia. 'os' refers to osteoderms, and the numbers refer to the different types. os(1) are the osteoderms covering the neck region; os(2) are the osteoderms covering the top of the trunk; and os (3) are the osteoderms covering the underside of the trunk (which may be scales; figure from Berman et al., 1985). The position of Ecolsonia within Dissorophoidea continued to remain unresolved into the 21st century until the development of computer-assisted phylogenetics and the recovery of more trematopid and dissorophid material that revealed that Ecolsonia is probably a trematopid, albeit an unusual one. Of the trematopids, Ecolsonia is the most heavily armoured one, with a series of four osteoderms that would have probably covered the neck and an extensive dorsal and ventral covering totally unlike anything seen in any other olsoniform. Unlike in dissorophids, whose osteoderms are confined to the backbone, it appears that Ecolsonia had ornamented osteoderms covering the entire trunk region, which hypothetically at least would have conferred more of a traditional "armour defence" compared to dissorophids in which the narrow osteoderm covering left a lot of the body uncovered. Probably they helped to stabilize the trunk region a bit as well. Anconastes vesperus

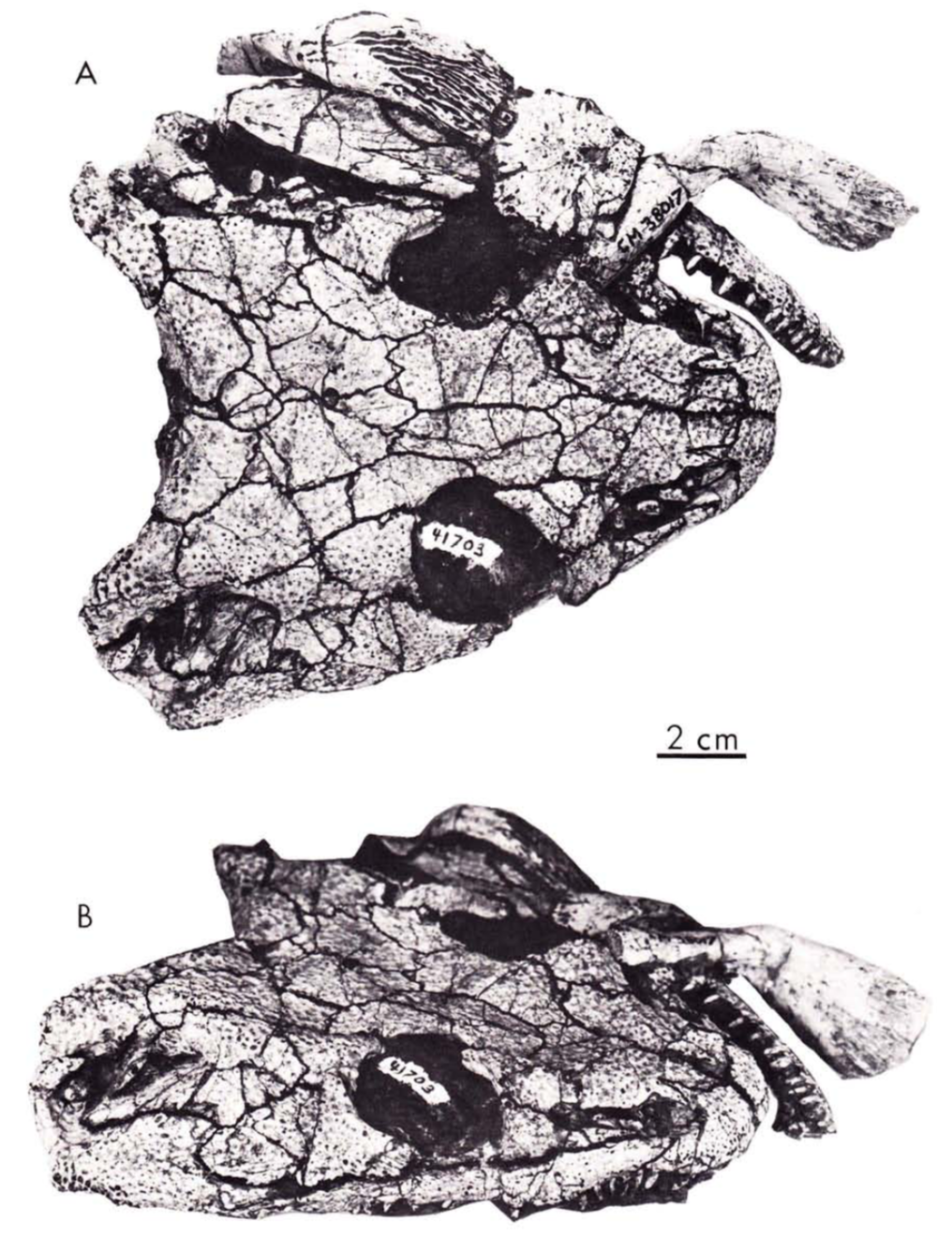

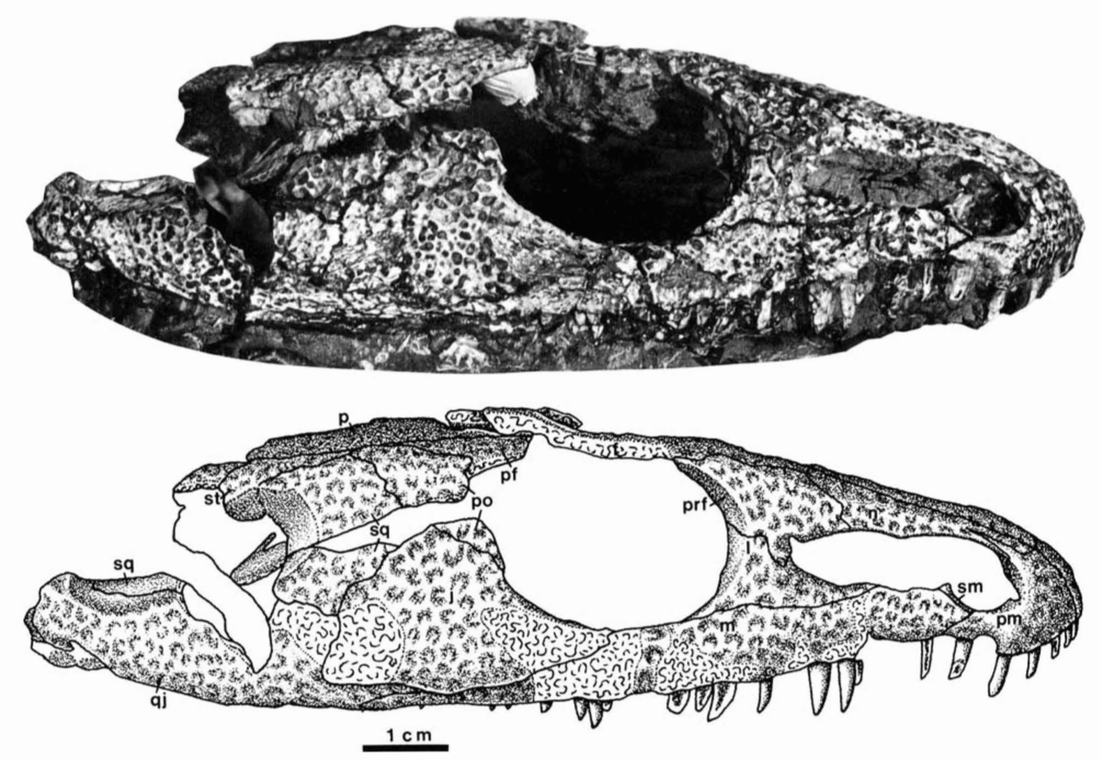

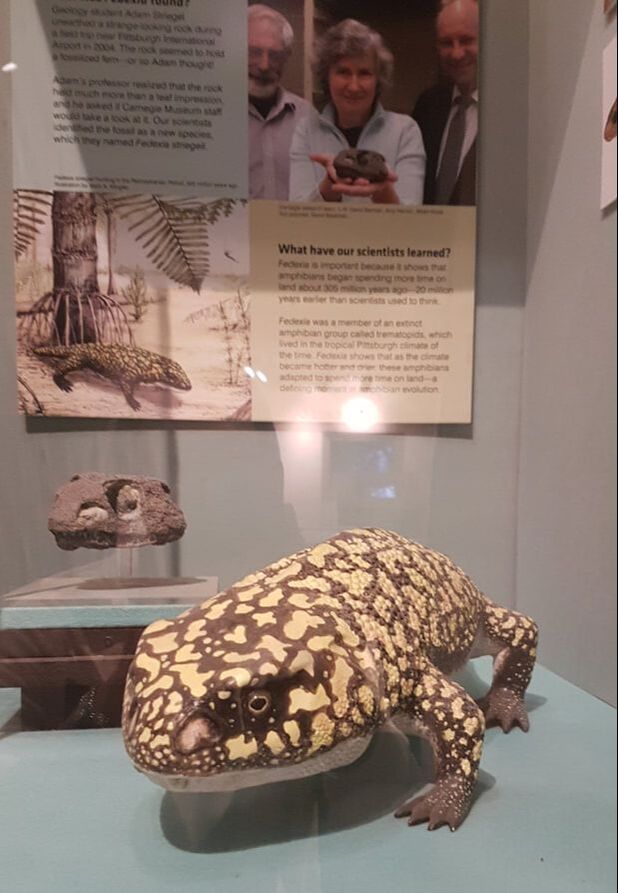

Fedexia striegeli

Trematopids are a pretty cool group that's really growing on me; they don't get quite as much attention as some of the other Paleozoic temnospondyls, probably because quite a lot of them are only known from a single specimen, but whatever that giant nostril was for is a neat anatomical feature (that maybe we will never really understand). Imagine these little guys running around chomping on other tetrapods - somebody should put that in a BBC documentary! Stay tuned for some more trematopid research coming out in 2020! If you visit the Carnegie (highly recommended), the cast and reconstruction of Fedexia are unfortunately the only trematopids on display, but you can find more trematopids on display at the Field Museum in Chicago! Refs

Nathan Parker

12/16/2019 03:41:56 pm

Your overview is very helpful. I've just begun reading up on trematopids. There've been so many synonymizations in this group, it gets confusing to the neophyte. Comments are closed.

|

About the blogA blog on all things temnospondyl written by someone who spends too much time thinking about them. Covers all aspects of temnospondyl paleobiology and ongoing research (not just mine). Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed